Product categories

|

Reporting periods

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Pillar | Earliest data | Latest data |

| Pension funds | Occupational (II) | 2002 | 2024 |

| Life insurance | Voluntary (III) | 2002 | 2024 |

Zusammenfassung

Rund 90% des durchschnittlichen Alterseinkommens in Österreich stammen aus dem öffentlichen Pensionssystem. Damit ist die Altersvorsorge sehr stark auf die erste Säule konzentriert. Die betriebliche Altersvorsorge ist freiwillig und wird in erster Linie von Pensionskassen und Versicherungsunternehmen getragen. Direktzusagen sind ein alternatives Instrument deren Nutzung seit Jahren stagniert. Die Möglichkeit für beitragsorientierte Pensionspläne in Pensionskassen und über Versicherungen hat die Verbreitung der betrieblichen Altersversorgung in Österreich gestärkt. Während betriebliche Formen der Altersvorsorge im Laufe der Zeit beliebter wurden, dämpften niedrige Zinssätze und die hohe Liquiditätspräferenz die Nachfrage nach individuellen Lebensversicherungsverträgen. In den Jahren 2002 bis 2024 war die Performance der Pensionskassen real und nach Abzug der Verwaltungskosten positiv; die annualisierte Durchschnittsrendite lag bei 0,9% vor Steuern. Die Lebensversicherungsbranche verfolgt eine deutlich konservativere Anlagepolitik und erzielte nach Berücksichtigung von Vertriebskosten eine durchschnittliche reale Nettorendite vor Steuern von 0,6% pro Jahr.

Summary

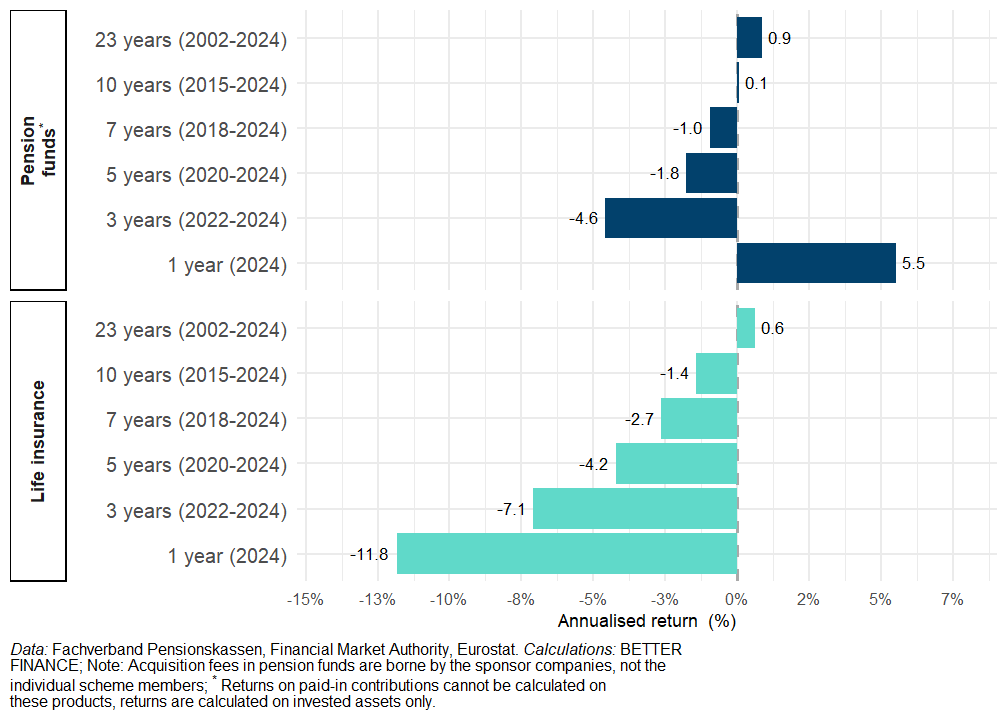

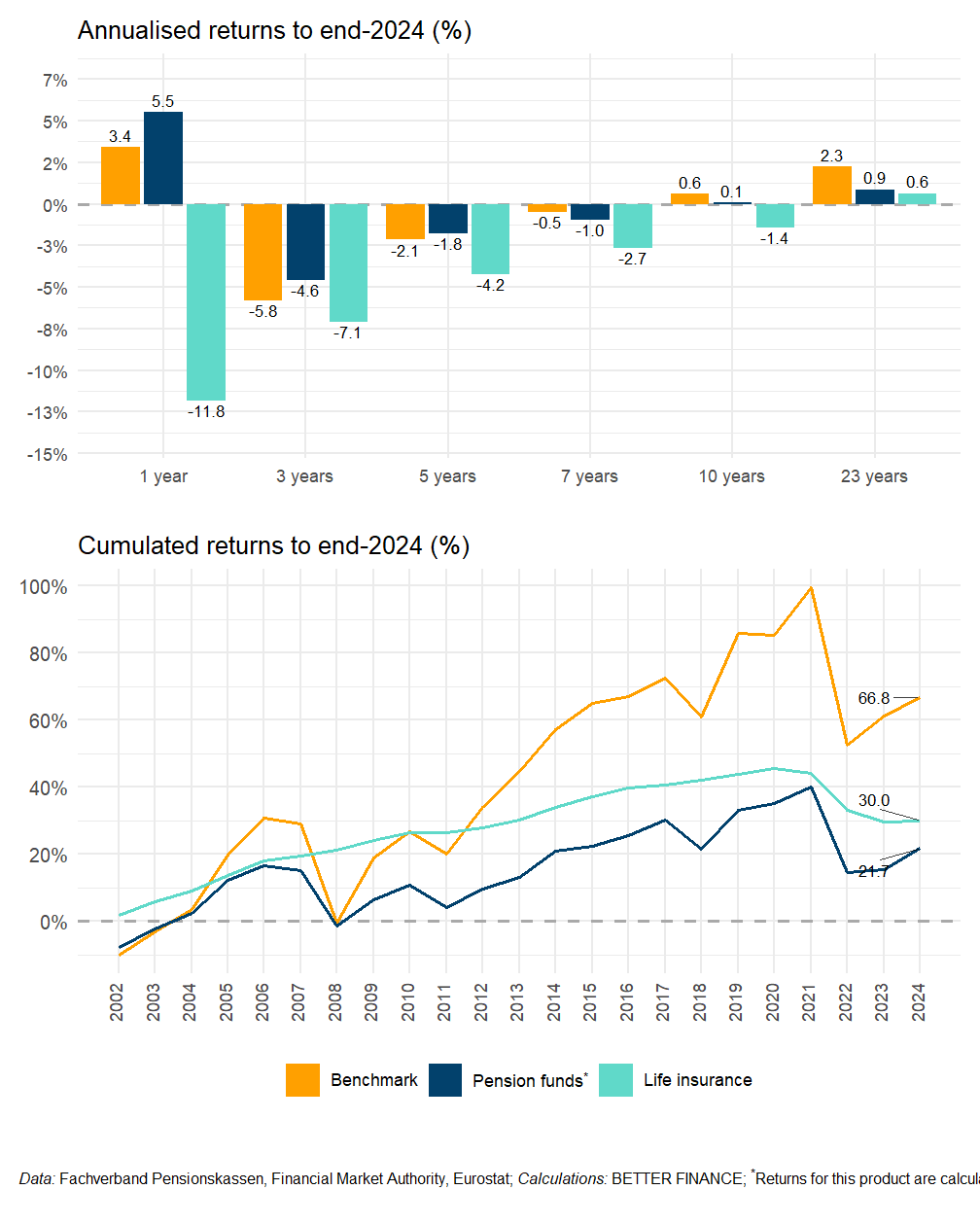

With around 90% of the average retirement income received from public pension entitlements, the Austrian pension system is very reliant on the first pillar. Occupational pensions are voluntary and primarily offered through pension funds and insurance companies. Direct commitments are an alternative vehicle, but their usage stagnates. The option for Defined contributions (DC) plans with favourable tax treatment offered either by pension funds or insurance companies boosted the prevalence of occupational pensions in Austria. While occupational pensions have become more popular over time, low interest rates and a high liquidity preference dampened demand for individual life insurance contracts. Over the years 2002 through 2024, the performance of pension funds in real net terms has been positive, with an annualised average return of 0.9% before tax. The life insurance industry followed a distinctly more conservative investment policy and achieved after subtracting distribution fees an average annual net real return before tax of 0.6%.

5.1 Introduction: The Austrian pension system

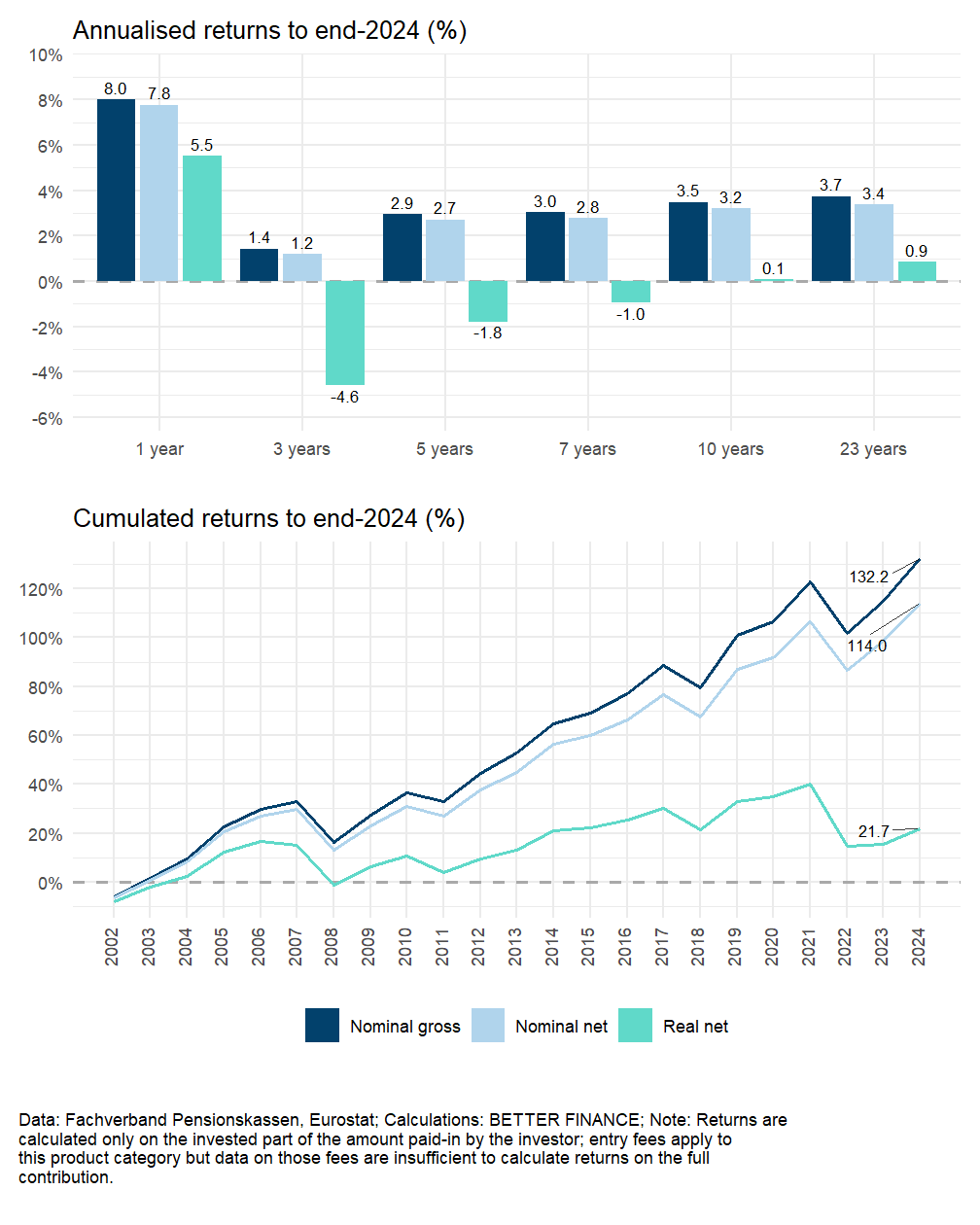

The main vehicles for old age provision within the second and third pillar are insurance companies and pension funds. The performance of pension funds in real terms remains positive over the whole period from 2002-2024, with an annualised average real return of 0.9% after service charges and before taxation. Especially the difficult years in 2002, 2007, 2008, 2011, 2018 and 2022 dampened the investment performance considerably. High inflation abated in 2024 and the good nominal return on investment made it possible to build back the fluctuation reserves which were almost depleted in 2022.

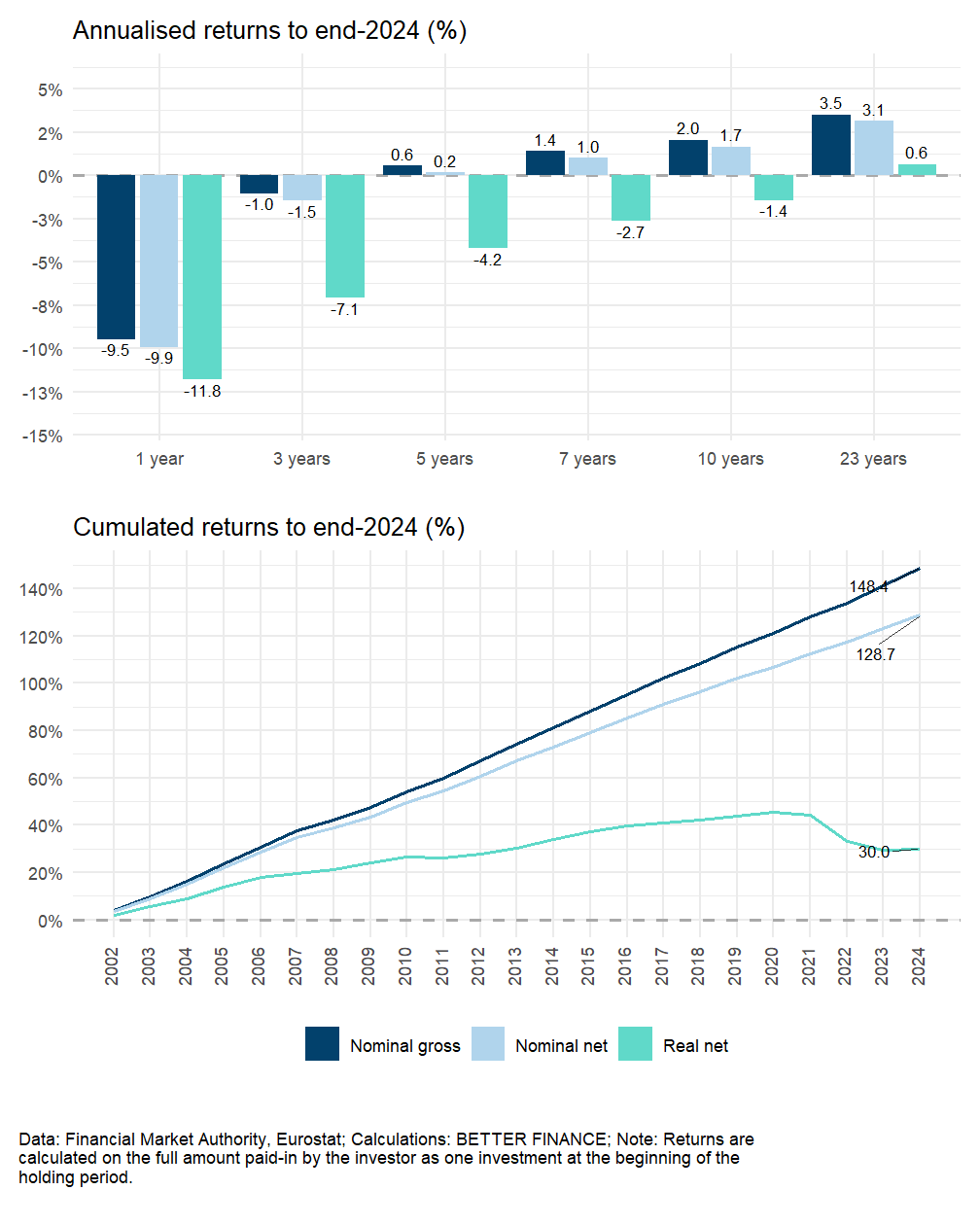

The average real rate of return on investments by insurance companies benefits from the conservative asset allocation with strong holdings of government bonds. This allowed insurers to avoid large losses in years with a financial market crisis and to reach an average real rate of return of 0.6% annually after distribution fees, service charges and before taxation. Low nominal yields on government bond investments in combination with the rate hiking cycle and unexpectedly high inflation rates depressed net real rates of return after 2015, in particular over the last four years.

Table 14.1 shows the categories of products for which real net returns are calculated in this chapter. The annualised nominal, net and real net rates of returns for the Austrian retirement provision vehicles are summarised in Table 14.2: They are based on different holding periods: 1 year, 3 years, 5 years, 7 years, 10 years and since inception (2002).

Holding period

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | 7 years | 10 years | Whole reporting period | to... | |

| Pension fundsa | 5.5% | -4.6% | -1.8% | -1.0% | 0.1% | 0.9% | end 2024 |

| Life insurance | -11.8% | -7.1% | -4.2% | -2.7% | -1.4% | 0.6% | end 2024 |

| a Entry fees apply to this product category but data are unavailable; returns are calculated on the invested part of contributions only | |||||||

| Data: Fachverband Pensionskassen, Financial Market Authority, OECD Pension indicators, Eurostat; Calculations: BETTER FINANCE | |||||||

| Note: Entry fees on pension funds are paid by sponsors (employer companies), not by individual scheme members | |||||||

Pension system in Austria: An overview

The Austrian pension system consists of three pillars:

- Pillar I: Mandatory Public Pension Insurance

- Pillar II: Voluntary Occupational Pensions

- Pillar III: Voluntary Individual Pensions

The mandatory public pension insurance covers most of private sector employees (Pillar I). Civil servants have their own pension system which will gradually converge towards the public pension insurance system. The self-employed belong to a separate mandatory system. The public pension system works as a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) scheme and was founded in 1945. The system covers 4.4 million people or 98.3% of the gainfully employed (2024). In 2024, all employees—except civil servants—were subject to a contribution payment of 22.8% of their income before taxes, with contributions shared between the employer (12.55%) and the employee (10.25%). If insured persons continue to work after their mandatory retirement age, the contribution rates will be halved. Civil servants pay a contribution of 12.55% of their gross wage and the self-employed pay 18.5% of their profit before taxes into the pension system. The Austrian pension system will be fully harmonized across all insured persons by 2050. The public pension system has an income ceiling (maximum contribution basis) up to which contributions apply, income above this level is exempted from contributions but the ceiling also limits the pension benefit level. In 2024 the ceiling was between EUR 6060 and EUR 7070, depending on the employment status. About 5% of the gainfully employed achieve an income above these ceilings. The theoretical gross pension replacement rate at the median income level for persons entering the labour market at age 22 corresponds to 74.1% of the average lifetime income while the net pension replacement rate is at 87.4% (OECD 2023). Both theoretical replacement rates will be reached after 43 years of uninterrupted employment with earnings always at the average income level. Effective replacement rates are likely to be lower because careers are not continuous and life-time income profiles are not flat. Due to pension reforms gradually taking effect, the effective replacement rates are expected to fall for future pensioners. Nevertheless, high replacement rates for many of the gainfully employed limit the demand for occupational as well as private pension plans.

Accompanying a series of public pension reforms between 2003 and 2006 which implemented reductions in the expected benefit level, the Austrian government introduced the premium subsidised pension plan to make private old-age provision more attractive. This scheme became very popular until 2012 with 1.64 million contracts signed but it lost attraction after the government halved the premium subsidy in 2012 (to 4.25% of the premium paid) and after investment yields collapsed during the financial crisis in 2007. Expiring contracts are rarely renewed and by 2024, only 0.8 million contracts were still active.

| Pillar I | Pillar II | Pillar III |

|---|---|---|

| Mandatory Public Pension Insurance | Voluntary Occupational Pensions | Voluntary Personal Pensions |

| Practically all gainfully employed persons are subject to pension contributions of 22.8% of income before taxes | Employers can establish an occupational pension system of their preference | Supplement particularly for high earners |

| Means tested minimum pension | Direct commitments, pension funds, occupational life insurance. 44% of employees are entitled | Life insurance with a coverage of about 41% of private households. The state-aided old-age insurance features 0.8 mln. contracts |

| Pension level depends on life time income (various kinds of supplementary insurance months are accounted, cf. motherhood, unemployment, military service) | ||

| Mandatory | Voluntary | Voluntary |

| PAYG | DB or DC | DC |

| Quick facts | ||

| Statutory retirement age is 61 (women) and 65 (men) | ||

| The average effective age of retirement was 60.4 for women and 62.4 for men (2024, including invalidity pensions and early retirement schemes but excluding rehabilitation benefits).1 | ||

| At 87.4% the theoretical net replacement rate in 2021 was considerably higher than the OECD average (61.4%).2 | ||

| The mandatory public pension system covers 4.4 mln. insured persons and pays pensions to 2.57 mln. beneficiaries3 | The voluntary occupational pension system covers 1.74 mln. entitled persons and pays pensions to 0.34 mln. beneficiaries3 | Voluntary personal pension plans cover 3.38 mln. entitled persons and pay pensions to 0.18 mln. beneficiaries3 |

| The average pensioneer receives 90% of his retirement income from public pensions | The average pensioner receives 4% of his retirement income from an occupational pension | The average pensioner receives 6% of his retirement income from a personal pension |

| Source: Own composition. 1 Hauptverband der österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger, Statistische Daten aus der Sozialversicherung, Pensionsversicherung, SV in Zahlen 3/2024. 2 OECD data. 3 Macrobond, Hauptverband der Sozialversicherungsträger: Die österr. SV in Zahlen 2025/3, WIFO. |

||

5.2 Long-term and pension savings vehicles in Austria

Private pensions are divided into voluntary occupational and voluntary personal pensions. About 6.5% of today’s retirees receive regular benefits from an occupational or personal pension. This figure is made up by 4% of retirees receiving benefits from an occupational pension and 2.5% of retirees receiving annuities from a personal pension plan (Url and Pekanov 2017). Given today’s number of active plan members these shares can be expected to have increased substantially over time.

Occupational pension vehicles (Pillar II):

At the beginning of 2003, the system of severance payments was replaced by mandatory contributions towards occupational severance and retirement funds (Betriebliche Vorsorgekassen). While the old severance payment regulations continue to apply to existing employment relations, employment contracts established after the end of 2002 feature mandatory contributions of 1.53% of gross wages to these funds. The main characteristics of severance payments have been transferred to the new system, i.e. in case of dismissal the fund will pay out the accumulated amount. Beneficiaries, however, may voluntarily opt to use this instrument as a tax-preferred vehicle for old-age provision. Less than one percent of the beneficiaries use this option. We, therefore, do not count occupational severance and retirement funds as pension vehicles in the following.

Life insurance and pension insurance contracts:

Life insurance policies are signed by private persons who pay contributions over an agreed period into their own pension account. The insurance company administrates the account and manages the accumulated assets. At the end of the contribution period, either a lump-sum amount is paid out to the insured person or alternatively, the insurer converts the accumulated capital into an annuity.

Second pillar: Direct Commitments, pension funds and collective life insurance

Occupational pension plans are typically provided on a voluntary basis by firms, only a few collective bargaining agreements include an obligation for member firms of the respective sector. Employers can also choose the coverage and the vehicle of their pension plan. There are three types of occupational retirement schemes:

- direct commitments funded by book reserves;

- pension funds, and;

- several types of life insurance schemes.

Each of these schemes has advantages and drawbacks. While direct commitments create a stronger link between employees and the firm, the future pension payments are subject to bankruptcy risk and, during the accumulation phase, the firm must either manage the assets backing the book reserves or seek some sort of reinsurance. External vehicles like pension funds or life insurance contracts imply less bonding because the vesting period is much shorter, but they also outsource the effort of investment choice and annuity payments to a financial intermediary. The design of a voluntary pension plan is at the full discretion of the employer, but usually an arrangement with the firm’s workers council is necessary.

Over the last decades many firms switched from direct commitment schemes to pension funds. On the one hand, this was a strategy to reduce the cost of existing defined benefit pension schemes by switching to DC plans, and on the other hand, these efforts made balance sheets shorter and cleaned them from items unknown to international investors.

Direct commitments (Direktzusage)

Direct commitments are pension promises by the employer to the employee that are administrated within a firm. These types of arrangements dominated until the 1980s, when several large bankruptcies or near bankruptcies revealed their fragility. The main two characteristics of this arrangement are direct administration of the pension obligation within the firm and a defined benefit type of the pension plan: the pension level is related to the wage level of employees. The plan administration comprises the computation of individual pension obligations and the respective book reserves, their coverage by invested assets, as well as the annuity payment. Nevertheless, many activities can be outsourced to actuaries, investment funds, and insurance companies. Pension claims based on direct commitments are not subject to any reinsurance requirement, but the reserve funds dedicated to back book reserves are protected from creditors. Besides outsourcing, the Insolvenz-Entgelt-Fonds provides a further safeguard for entitled employees and pensioners to bankruptcy risk. This fund is a public fund covering wage entitlements by employees in case of bankruptcy. Currently, the Insolvenz-Entgelt-Fonds covers a maximum of 2 years of benefit payments or accrued entitlements (Insolvenz-Entgeltsicherungsgesetz, § 3d). Due to their voluntary character and a lack of supervision the incidence of direct commitments is hardly documented.

Pensions funds (Pensionskassen)

Pension funds are specialised financial intermediaries providing only services related to occupational pensions, i.e. they collect contributions, manage individual accounts, invest the accumulated capital, and they pay out an annuity to beneficiaries. Pension funds were introduced in 1990 with the Occupational Pension Law and the Pension Fund Law (Betriebspensions- und Pensionskassengesetz) which established a general legal basis for occupational pension schemes including pension funds. These laws facilitated the outsourcing of asset management and accounts administration from direct commitment systems into pension funds. This made individual pension entitlements transferable between companies, it made possible additional contributions by employees, but it also enabled firms to switch from defined benefit to DC pension plans. By now, most pension plans are of the DC type and beneficiaries are directly exposed to investment risk as well as to changes in mortality risk. For example, plan members whose entitlement was converted from a direct commitment into an entitlement vis-a-vis a pension fund still suffer from investment losses shortly after transferring the assets into pension funds around the year 2000 because the imputed interest rates used at that time were overly optimistic (Url 2003).

Pension funds may be either multi-employer pension funds, i.e. they are open to all firms, or alternatively, they may be firm-specific pension funds (single-employer pension funds) administrating the pension plan for a single firm or a holding group. Over the last couple of years, many firm-specific pension funds have been merged into multi-employer pension funds by constructing independent risk and investment pools like Undertaking for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (UCITS). Pension funds are subject to supervision by the Austrian Financial Market Authority and they feature investment advisory boards, where representatives of workers and employers can advance their opinion on the investment strategy. Nevertheless, the results from asset-liability management strategies dominate the portfolio choice of pension funds.

Pension funds offer primarily annuities because lump-sum payments are restricted to accounts with very small accumulated assets. Pension funds have to offer accounts with guaranteed long-term yields on investment linked to the market yield of Austrian government bonds, although this option lost attractiveness due to the high costs of guarantees and a substantial weakening of the extent of the guarantee. The guarantee is backed by the own capital of the pension fund and by a minimum return reserve fund financed by contributions from beneficiaries (Mindestertragsrücklage). In case of bankruptcy of the pension fund, all entitlements are protected by separate ownership of the assets associated to each account (Deckungsstock).

Direct insurance

Firms can alternatively sign a contract with a life insurance company. This contract is either subject to the regulation covering occupational pensions (Betriebliche Kollektivversicherung) or it is designed as a life insurance policy and is subject to the regulation for life insurance products. Insurance companies also underwrite risks embedded in direct commitments. Direct insurance of occupational pension plans implies that the sponsoring firm will pay contributions into a life insurance contract with employees as beneficiaries. In this case, the firm outsources the management of personal accounts and assets, as well as the annuity payments to an insurance company.

The number of working and retired persons holding a life insurance policy is almost double the number of members in occupational pension plans. Despite high public pension levels and the voluntary character of occupational pensions, their use is comparatively widespread in Austria. There are two reasons for this: (1) the public sector offers an occupational pension scheme, and (2) occupational life insurance policies benefit from a tax loophole. Contributions up to EUR 300 annually are tax-exempt—as per § 3/1/15 of the Einkommensteuergesetz (EStG), the Income Tax Act—and as a result around 636 000 contracts have been signed until 2024. Given the small pension wealth accumulated in these accounts, one cannot expect reasonable annuity payments resulting from this vehicle.

The Betriebliche Kollektivversicherung, on the other hand, provides occupational pensions with a favourable tax treatment up to 10% of individual gross wages. It is regulated according to the Occupational Pension Law, but this vehicle allows for more substantial long-term guarantees usually offered by classic life insurance contracts. Insurers also freeze mortality tables at the date of joining the pension plan.

Third pillar: Classic and Unit-linked life insurance

There are two types of insurance contracts available which can be distinguished according to who bears the investment risks. Insured persons with a unit-linked policy assume the investment risk and must choose their investment portfolio. Classic life insurance products, on the other hand, offer a minimum return guarantee but investment decisions are delegated to the insurance company. The maximum possible guaranteed rate of return is regulated by the Austrian supervisory authority; currently, this rate is fixed at 0% per annum (since July 1st, 2022; BGBl. II Nr. 354/2021). Investment returns in excess of the guaranteed level are distributed across insured persons as variable profit participation.

The major public pension reforms between 2003 and 2006 left many private employees, employers, and civil servants with a lower expected public pension payment. As a compensation the Austrian government introduced the premium subsidised pension plan (Prämienbegünstigte Zukunftsvorsorge). Originally the premium was fixed at 9.5% of the annual contribution, but in 2012, fiscal consolidation measures resulted in a halving of the subsidy rate; it is currently fixed at 4.25%. Additionally, the yield on investment is fully tax-exempt. Premium subsidised pension plans have a minimum contract length of 10 years. The portfolio choice for the assets of subsidised pension plans is restricted by law. A minimum share of the assets must be held in equities listed on underdeveloped stock exchanges. This measure was targeted to foster investment at the Vienna stock exchange, but it resulted in highly concentrated investment risk. The strict regulation of investments has been weakened over the past years allowing for example life cycle portfolios with a reduction of the equity exposure when the retirement date of entitled persons comes closer.

The halving of the subsidy premium in 2012 and substantial losses on stock exchanges during the years 2008 and 2022 reduced the demand for this pension saving vehicle. The number of contracts is falling and contracts with the shortest possible duration of ten years have been mostly terminated with a lump-sum payment. This triggers an exit from the annuity phase with a mandatory repayment of the subsidy. In 2024 the number of new contracts was 8077; with 65 000 contracts expiring in that year, the number of active contributors declined to 0.8 million persons.

5.3 Charges

Charges of pension funds

Information on all types of charges for occupational and private pension products are hard to obtain. Within direct commitment systems, pensions are of the defined benefit type and firms cover all expenses. The remaining vehicles for occupational pensions are subject to some degree of competition between financial intermediaries, although most pension funds are owned by alliances of banks and insurance companies. Because occupational pension plans are always group products, the individual entitled person has only limited or even no choice during the savings and annuity phases, thus these products have a cost advantage over individual pension plans. Large firms also receive quantity discounts or customised tariffs with lower administrative charges. In Table 5.4, administrative charges and investment expenses for pension funds are expressed as a percentage of the funds’ total invested assets. Employers pay any costs of establishing the contract with a pension fund or an insurance company and the consultants used; there are no data published on this type of costs. From the perspective of a beneficiary there are no acquisition costs associated with payments into pension funds. Except the opportunity of voluntary additional payments to the employer based payment, there are no possibilities to customise the contract terms to personal preferences. In the year 2019, a substantial reduction in charges has been recorded by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

| Year | Admin. and mgt. fees |

|---|---|

| 2003 | 0.18% |

| 2004 | 0.12% |

| 2005 | 0.14% |

| 2006 | 0.15% |

| 2007 | 0.15% |

| 2008 | 0.16% |

| 2009 | 0.17% |

| 2010 | 0.17% |

| 2013 | 0.16% |

| 2014 | 0.17% |

| 2015 | 0.18% |

| 2016 | 0.18% |

| 2017 | 0.18% |

| 2018 | 0.19% |

| 2019 | 0.12% |

| 2020 | 0.10% |

| 2021 | 0.11% |

| 2022 | 0.12% |

| 2023 | 0.12% |

| 2024 | 0.12% |

| Data: OECD Pension indicators Calculations: BETTER FINANCE. | |

Charges of life insurance products

The costs of acquisition and administration for life insurance products are published by the Financial Market Authority. Acquisition costs amount to roughly one tenth of total premium income (see Table 5.5). Since January 1st, 2007, the Insurance Contract Law includes a provision that acquisition fees have to be distributed over at least the first five years of the contract length. Before 2007 it was possible to charge the full acquisition fee in the first year, making the cancellation of a life insurance contract extremely costly. Administration costs are presented as a ratio to the mean of the invested assets.

Since January 1st, 2017, every consumer receives a piece of short product information—the Key Information Document (KID)—before signing an insurance contract. These information sheets are standardised and contain details of individual charges and investment fees allowing a better comparison of offers.

| Year | Acquisition fees1 | Admin. and mgt. fees |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 11.28% | 0.43% |

| 2006 | 11.49% | 0.38% |

| 2007 | 11.10% | 0.38% |

| 2008 | 10.66% | 0.38% |

| 2009 | 9.97% | 0.37% |

| 2010 | 10.75% | 0.36% |

| 2011 | 11.01% | 0.39% |

| 2012 | 11.68% | 0.33% |

| 2013 | 11.37% | 0.32% |

| 2014 | 10.67% | 0.33% |

| 2015 | 10.80% | 0.33% |

| 2016 | 11.49% | 0.35% |

| 2017 | 10.44% | 0.36% |

| 2018 | 10.27% | 0.37% |

| 2019 | 10.57% | 0.37% |

| 2020 | 10.85% | 0.38% |

| 2021 | 10.91% | 0.37% |

| 2022 | 11.01% | 0.40% |

| 2023 | 11.73% | 0.44% |

| 2024 | 12.09% | 0.46% |

| 1 % of premiums | ||

| Data: Financial Market Authority Calculations: BETTER FINANCE. | ||

5.4 Taxation

The taxation of old-age provision varies over different vehicles and depends mainly on the history associated to the vehicle. For example, the taxation of occupational pensions is very much oriented towards the treatment of direct commitments, which were the first vehicle used for occupational pensions. Direct commitments work like a deferred compensation and therefore they are only taxed in the year of the payment. This corresponds to a system with tax-exempt contributions, tax-exempt capital accumulation, and (income) taxed benefits (EET system). This philosophy carries over to contributions paid by the employer into a pension fund or a group insurance product following the pension fund regulation (Betriebliche Kollektivversicherung). Contributions to pension funds and group insurance products (Betriebliche Kollektivversicherung) are subject to a reduced insurance tax of 2.5%. Contributions by employees are fully taxed but the resulting annuity is subject to reduced income taxation.

Contributions to classic life insurance products are not tax deductible and are subject to an insurance tax of 4%. During the capital accumulation phase all investment returns are tax-exempt, and the taxation of benefits depends on the pay-out mode. Lump-sum payments are tax-free while annuities are subject to (reduced) income taxation. Additionally, premium subsidised products carry a premium based on the contribution, the capital accumulation phase is tax-exempt, and benefits are also tax free if they are converted into an annuity. Url and Pekanov (2017) provide a survey of the tax treatment of all vehicles for old-age provision using the present value approach as suggested by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2015, 2016). This approach compares the tax treatment of each vehicle to the tax treatment of a standard savings account. Expressed as a ratio to the present value of contributions, the tax advantage of employer payments into pension funds amounts to 20%, i.e. the value of the tax subsidy corresponds to one fifth of life-time contributions. The lowest tax advantage results for life insurance products with an annuity payment. In this case, the tax subsidy makes up for 7% of life-time contributions. The maximum tax advantage is associated with occupational life insurance policies subject to § 3/1/15 EStG. In this case, the subsidy amounts to 60% of lifetime contributions, however, payments into this vehicle are restricted to a negligible EUR 300 per year.

| Product categories |

Phase

|

Fiscal Regime | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contributions | Investment returns | Payouts | ||

| Pension funds | Exempted | Exempted | Taxed | EET |

| Life insurance | Taxed | Exempted | Taxed | TET |

| Source: BETTER FINANCE own elaboration, based on EStG. | ||||

5.5 Performance of Austrian long-term and pension savings

Real net returns of Austrian long-term and pension savings

Due to the defined benefit character of pensions derived from direct commitments and because accumulated assets for direct commitments have the narrow purpose of protecting individual pension claims in case of a firm bankruptcy, we do not compute pension returns for this vehicle. Furthermore, the asset class in which firms can invest are restricted to government bonds issued by OECD member countries.

The way of taxing contributions, investment returns, and pension payments varies according to the vehicle chosen, the party paying the contribution, i.e. employers or employees, and the personal income tax break of the retiree (see Section 5.4). For this reason, we cannot compute a general after-tax return for Austria. Instead, we present the:

- nominal returns before charges, inflation, and tax;

- nominal returns after charges but before inflation and tax;

- real returns after charges and inflation but before tax

for the two most important vehicles, i.e. pension funds and classic life insurance policies. For life insurance products an entry fee corresponding to the column showing the acquisition costs in Table 5.5 is subtracted in the first year of each holding period. The returns on classic life insurance policies are also representative for occupational pension plans using life insurance products under the occupational pension law (Betriebliche Kollektivversicherung) but in this case no acquisition costs are subtracted because employers pay all costs associated with setting up a contract with an insurance company and related consultancy work.

Inflation in Austria reached its peak early in 2023. The disinflation process in Austria continued throughout 2024 ending at 2.1% in December. Compared to 2023 the inflation differential to the EU reversed. Throughout the year government support measures to alleviate the burden of energy costs on private households lowered energy prices relative to the EU, while prices for services put pressure on Austria’s harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP). On average this resulted in an inflation differential towards the EU of 0.6 p.p.

Pension funds

Figure 5.5 shows the returns on assets held by pension funds. In the case of a defined benefit pension plan, investment returns are important for the sponsoring firm because if the return falls short of the imputed interest rate used for the computation of the expected pension level, the firm will have to provide additional contributions covering the shortfall. On the other hand, if a DC pension plan has been established, the beneficiaries bear the risk of a shortfall in the realised return on investment, and consequently, the realised pension level falls below its expected value.

Information on the net performance of pension funds is published continuously by an independent third party, the Oesterreichische Kontrollbank,1 following a standardised procedure. Aggregate returns are available for pension funds and for multi- and single-employer pension funds. The long-term performance of firm-specific pension funds is about 0.3 p.p. higher as compared to multi-employer pension funds. The difference results probably from a less risk-oriented investment style implemented by multi-employer pension funds, due to the wider usage of return guarantees in multi-employer pension funds. Nominal investment returns before charges result from adding administrative charges and investment charges of pension funds as presented in the section on charges to the net returns. Real returns are computed by adjusting for the HICP inflation rate in Austria.

The Financial Market Authority publishes the asset allocation of pension funds as of year-end (FMA n.d.). Due to the good performance of share prices over the last two years, the portfolio in 2024 continues to be dominated by equity investments (39.3%) with debt securities ranking second (33.6%). After the tumultuous year 2022, yields on risky assets became calmer again and fund managers reduced their cash holdings further (6.5%). Real estate investment (5.8%), on the other hand, took a hit from the ongoing decline in commercial property valuations. Pension funds still diversify their portfolio into the banking business by issuing loans and credits (3.0%). The remainder was mixed throughout smaller asset categories (see Figure 5.2). Given the strong exposure to equity, we find several years with negative returns, i.e. investment losses. Specifically, during the years after the bursting of the dot-com bubble (2000), the international financial market crisis (2007), and the public debt crisis in the euro area (2011), but also in 2018 and 2022, when both bond and equity markets lost value. Nominal returns slightly increased in 2024 and due to the successful disinflation real returns rose sharply. Nevertheless, between 2002 and 2024 pension funds achieved an annual average net real yield on investment of 0.9%. The nominal return before charges of 3.7% corresponds to a nominal average excess return over Austrian government bonds of 1.8 p.p.

Life insurance contracts

The return on investment in the classic life insurance industry is regularly computed by the Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO). This computation excludes unit-linked contracts because the investment risk is borne by the insured and returns are usually retained within mutual funds and reinvested. The calculation of investment returns is based on investment revenues of the insurance industry and the related stock of invested assets in classic life insurance as provided by the Financial Market Authority. The method uses the mean amount of invested capital over the year as the basis for the computation and is documented in Url (1996). The charges used to correct the yield for acquisition costs on the initial payment and the running administrative expenses are based on Table 5.5. Real returns result from the adjustment of nominal returns using the HICP inflation rate for Austria (Figure 10.2). Figure 5.6 shows the nominal gross, nominal net and real net returns of Austrian life insurance policies.

Obviously, nominal gross returns in the insurance industry are less volatile than in the pension fund industry. The main reason for this divergence is the more conservative asset allocation of life insurance companies, i.e. they invest heavily in bonds (54%) and the share of collective investments in their portfolio (24%) is also concentrated in bonds-oriented investment funds, creating a high exposure to fixed-interest securities (FMA n.d.). Another important asset class in the insurance industry are shareholdings in related undertakings (8%), which are usually not listed on a stock exchange. Property investments sum up to 8% of the assets, while equity holdings form just 1.2% of the portfolio (Figure 5.3). This gives insurance companies small exposure to volatile asset categories and consequently their investment performance is steadier.

The particular way of distributing investment returns in classic insurance policies makes their performance even more steady for beneficiaries. Insurance companies separate their investment income into two parts. The first part serves to cover underwritten minimum return guarantees and it is immediately booked towards the individual account. Any excess return will be distributed over a couple of years through the build-up and reduction of profit reserves. By transferring accumulated profit reserves smoothly into individual accounts, insurance companies make the individual accrual of investments returns less dependent on current capital market developments although asset values are marked to market.

By summer 2024, the yields on 10-year German government bonds (benchmark) had risen by 30 basis points, but in the course of lowering the European Central Bank (ECB) key interest rates, bond yields went back to their levels from the start of the year. Consequently, the negative yield curve flattened. In comparison to 2023, European bond markets calmed down and spreads vis-a-vis the German benchmark bond narrowed for most countries. Insurance companies managed to keep their nominal return almost constant in 2024. For the first time since 2020 real returns on invested assets climbed back into positive territory, at 0.4%, because the inflation rate was so low. Acquisition costs are subtracted fully from the initial premium payment, therefore short-run nominal yields after accounting for entry fees and administrative charges are negative. This illustrates the cost effects of consumer marketing, regulatory information duties, financial advice, and the individual adjustment of contracts. The negative effects of entry fees on short-term returns (see Table 5.7) render life insurance a long-term investment product. Including acquisition costs, the long-run net real return (2002-2024) on insurance investments remained constant at 0,6%. The nominal return before charges of 4.0% corresponds to a nominal average excess return over Austrian government bonds of 2.1 pp. The long-term investment performance before acquisition costs and charges continues to exceed that of pension funds.

Return on full contribution (paid-in amount)

|

Return on invested assets (contribution minus entry fees)

|

Effect of entry fees on return (percentage points)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annualised | Cumulated | Annualised | Cumulated | Annualised | Cumulated | |

| 1 year (2024) | -11.8% | -11.8% | 0.4% | 0.4% | -12.2pp | -12.2pp |

| 3 years (2022-2024) | -7.1% | -19.8% | -3.4% | -9.8% | -3.7pp | -10.0pp |

| 5 years (2020-2024) | -4.2% | -19.4% | -2.0% | -9.6% | -2.2pp | -9.8pp |

| 7 years (2018-2024) | -2.7% | -17.2% | -1.1% | -7.6% | -1.5pp | -9.5pp |

| 10 years (2015-2024) | -1.4% | -13.4% | -0.3% | -2.9% | -1.1pp | -10.5pp |

| 23 years (2002-2024) | 0.6% | 15.6% | 1.1% | 30.0% | -0.5pp | -14.4pp |

| Data: Financial Market Authority. | ||||||

Do Austrian savings products beat capital markets?

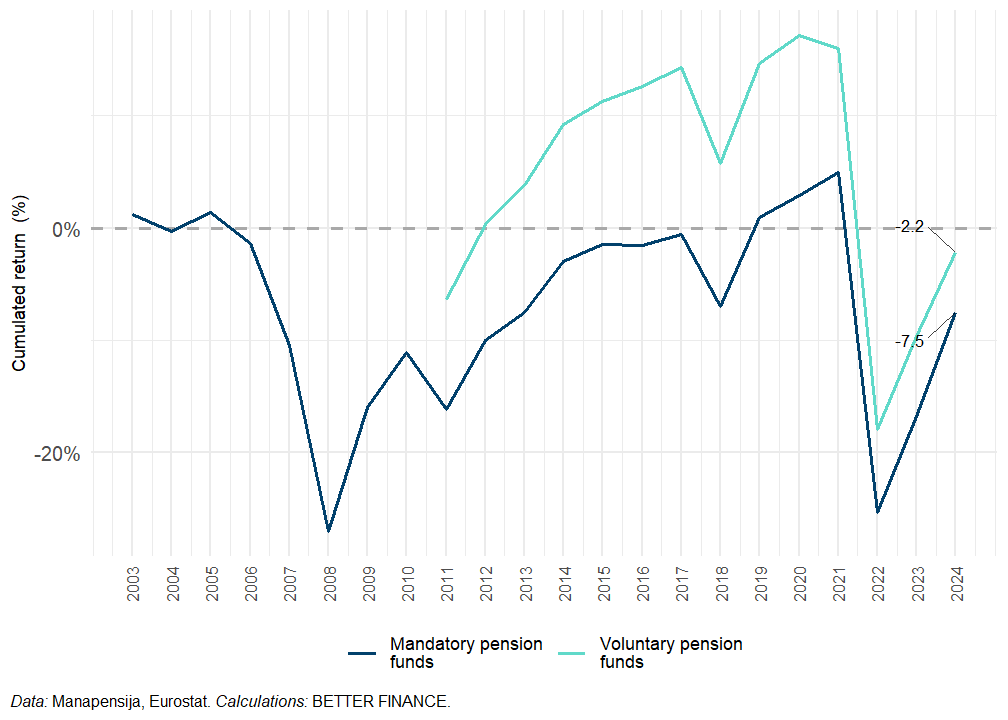

In the long run, pension funds and life insurance products reached excess returns over the yield of Austrian government bonds in the size of 1.8 and 2.1 pp., respectively. Another possible yardstick are yields from benchmark portfolios with equal holdings of equity and bonds (see Table 8.7). The net real return of pension funds in 2024 was beating the benchmark portfolio by 2.1 pp. The real excess return of pension funds over the benchmark portfolio between 2002–2024 was still negative at -2.0 pp., i.e. the long-term performance of pension funds was lagging the benchmark portfolio (Figure 5.9).

| Equity index | Bonds index | Start year | Allocation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pension funds | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2002 | 50%–50% |

| Life insurance | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2002 | 50%–50% |

| Data: STOXX, Bloomberg; Note: Benchmark porfolios are rebalanced annually. | ||||

Acquisition costs and the more cautious investment strategy of the insurance industry go along with a real net return of life insurance products of -11.8% in 2024, which was substantially below the benchmark portfolio’s performance in 2024 of 3.4%. In the long run, the performance of life insurance products is catching up, but still falls behind the benchmark portfolio. From 2002–2024, the real excess return of life insurance products was -2.2 pp., i.e. when accounting for acquisition costs, classic life insurance products carrying a minimum return guarantee showed a lower real net return than the benchmark portfolio.

5.6 Conclusions

The performance of pension funds in real terms remains positive over the whole period from 2002-2024, with an annualised average real return of 0.9% after service charges and before taxation. Especially the difficult years in 2002, 2007, 2008, 2011, 2018 and 2022 dampened the investment performance considerably. The favourable nominal result in 2024 allowed pension funds to replenish exhausted fluctuation reserves and to recover the purchasing power of retirees, lost over the inflationary period 2022-2023. All major stock exchanges have seen their valuation increase until mid-August of 2025 while volatility has come down, offering a good earnings outlook for pension funds.

The average real rate of return on investments by insurance companies benefits from a conservative asset allocation with strong government bond holdings. This allowed insurers to avoid large losses in years with a financial market crisis and to reach an average real rate of return of 0.6%% annually after acquisition costs, service charges and before taxation. Low nominal yields on government bond investments in combination with unexpectedly high inflation pushed net real returns into negative territory between 2021 and 2023 but rapid disinflation throughout 2024 brought the real return on invested assets back into positive territory. From the perspective of pension savers, life insurance policies carry an acquisition fee which reduces the amount of invested capital upfront. This creates negative net returns over short investment horizons. Insurance companies benefit from the long duration of their investment portfolio, i.e. they still own bonds featuring high interest coupons. With the ECB unwinding its Asset Purchase Programme (APP) since July 2023 and its Pandemic Emergency Purchasing Program (PEPP) since the beginning of 2025, newly issued bonds can be expected to yield higher returns over the next years. Meanwhile the flat yield curve creates an incentive to extent the duration of bond portfolios, thus adding demand for longer-dated bonds. Furthermore, demographic trends can be expected to exert downward pressure on real rates over the coming years (Carvalho et al. 2025). Given weak survey data on consumer confidence, private households will retain their high liquidity preference and reduce their demand for classic life insurance. Premium subsidised pension insurance is also in low demand because subsidies were halved in 2012.

By now, the forecasted economic upturn for 2025 has proved to be overly optimistic. High wage settlements in previous years did not raise private household consumption, rather households preferred to reduce their indebtedness and increase their term deposits in banks. In 2024 most new jobs had been created in the public sector (public administration, health, and education), where occupational pensions are part of the pay package. Given that Austria entered a EU—excessive deficit procedure the public sector will not be able to continue on this recruitment path and private firms will be reluctant to offer additional voluntary occupational pension contracts, so the number of beneficiaries is likely to stagnate in 2025, while private demand for life insurance products will remain low. Furthermore, the minimum age to enter a public pension will be lifted and requirements for early retirement stiffened, thus labour market tightness will decrease. In the medium term, large cohorts will pass the mandatory retirement age. Given the shortages of qualified labour, firms may consider extending payment packages with immediate impact on their employees, like voluntarily overpaying collective wage contracts or providing fringe benefits in terms of more flexible working hours.

The opportunity to offer DC plans has certainly boosted the spread of occupational pensions in Austria. Within pension funds 98% of the entitlements are now DC plans, while occupational pensions based on insurance contracts are exclusively of the DC type. In summer 2025, social partners in Austria agreed on a common proposal to introduce a general pension funds contract, which would enable employees of firms not offering an occupational pension plan to transfer their severance payment (up to one year’s gross wage) into a pension fund for annuitization. Furthermore, the premium subsidy for voluntary payments by employees according to § 108a EStG, the Income Tax Act, should be converted from a percentage of the premium to a fixed amount. This increases the attractiveness to top-up the employer-based payment for low-income earners. Other components of the proposal include improving the transparency of account information and allowing contribution rates to vary with operational key figures. Austria’s financial services industry still does not offer products according to the Pan-European Personal Pension regulation.

Acronyms

- APP

- Asset Purchase Programme

- DC

- Defined contributions

- ECB

- European Central Bank

- EStG

- Einkommensteuergesetz

- HICP

- harmonised index of consumer prices

- KID

- Key Information Document

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PAYG

- pay-as-you-go

- PEPP

- Pandemic Emergency Purchasing Program

- UCITS

- Undertaking for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities