Product categories

|

Reporting periods

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Pillar | Earliest data | Latest data |

| Life insurances | Voluntary (III) | 2000 | 2024 |

Zusammenfassung

In Deutschland verfügen die Lebensversicherer bei der privaten und betrieblichen Altersvorsorge über eine dominante Position. Pensionskassen und Pensionsfonds als Einrichtungen betrieblicher Altersvorsorge (EbAv) spielen eine weniger wichtige Rolle im Vergleich zu anderen EU-Mitgliedsstaaten. Durch die Niedrigzinsphase der 2010er Jahre hat ein tiefgreifender Wandel von Garantieprodukten zu Kapitalmarkt näheren Produkten stattgefunden. Dieser Trend dürfte auch durch die Zinswende seit 2021/22 nicht wieder rückgängig gemacht werden.

Nachdem über Jahre die Inflation in Deutschland häufig unter dem EU-Durchschnitt gelegen hatte, wird die nun höhere Inflation für die Altersvorsorgesparer für einen dramatischen Verlust an langfristiger Kaufkraft sorgen, falls sie nicht eingedämmt werden kann. Als besonders problematisch müssen die hohen Kostenbelastungen der Lebensversicherer, insbesondere durch die Vertriebsvergütungen, angesehen werden.

In den letzten Jahren hat es intensive öffentliche Debatten über die Reform der staatlich geförderten Altersvorsorge, namentlich der Riester-Rente, gegeben. Deren Neugeschäft ist seit einigen Jahren praktisch zusammengebrochen, ihr Bestand nimmt sogar ab. Nach dem vorzeitigen Scheitern der „Ampel“-Koalition gibt es bisher nur unvollständige Informationen über die Reformvorhaben der neuen Bundesregierung (seit Mai 205 im Amt) hinsichtlich Rente und Altersvorsorge.

In der Gesetzlichen Rentenversicherung besteht ein massives Problem der langfristigen Finanzierbarkeit auf Grund des fortschreitenden demographischen Wandels und sozialpolitisch motivierter Rentenerhöhungen der letzten Jahre. Der Zielkonflikt zwischen Schuldenbegrenzung der öffentlichen Finanzen und sozialpolitischen Ambitionen dürfte sich in Zukunft immer weiter verschärfen…

Summary

In Germany life insurers play a dominant role in the private and occupational retirement provision sectors. Amongst occupational pensions, Pensionskassen and Pensionsfonds (IORPs) are less prominent compared to other EU member states. Due to the low interest rate environment of the 2010s, a significant shift occurred from pension products with guarantees to those with reduced guarantees or hybrid investments. The reversal of the Euro key interest rates in 2021/22 is unlikely to reverse this trend.

For years, inflation in Germany was lower than the EU average. However, the current higher inflation rate will result in a dramatic loss of long-term purchasing power for policyholders if inflation cannot be reduced. It is particularly concerning to consider the impact of distribution costs of life insurers on the real return.

In recent years, there have been intensive public debates, especially regarding the Riester Pension, which is a state-subsidised private pension product. Their new business has significantly declined, and their portfolio has even decreased. Following the premature collapse of the ‘traffic light’ coalition, there is currently only incomplete information available about the reform plans of the new federal government (in office since May 2025) with regard to pensions and retirement provision.

The mandatory First Pillar Pension System faces a significant challenge in maintaining its long-term financial balance due to demographic change and socially favourable increase of payouts. The conflict of objectives between limiting public debt and generous welfare policies will become increasingly pronounced in the future…

11.1 Introduction: The German pension system

German life-insurers publish rather detailed figures on new business and their portfolios, both in terms of the number of contracts and the gross written premia (GWPs) for various sub-categories of life and pension products. Their association, Gesamtverband der Versicherer (GDV), only publishes aggregate figures on costs and net returns of their assets under management. Average figures for gross returns of life-insurance products are published by thenational competent authority (NCA), the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin). Therefore, calculations following the methodology of this report can only be done in aggregate for life-insurers. However, more detailed figures on other occupational pension product providers—mainly institutions for occupational retirement provision (IORPs)—will be outlined based on additional sources.

At the product level, policyholders have access to detailed information on costs and performance scenarios. This information is provided through various pre-contractual information documents based on European Union (EU) regulation—forinsurance-based investment products (IBIPs)—and/or national law—for occupational and state-subsidised pension products.

With the end of the low-interest-rate phase, primarily in the 2010s, the following main developments can be confirmed for the German life insurance and pension products market:

- Continuously growing GWP, but decreasing in 2022 and 2023;

- Continuously growing market share of products with reduced guarantees, hybrid or unit-linked products (instead of classical guarantees during the accumulation phase);

- Continuously growing market share of pension products replacing traditional life-insurance. However, at the same time, we need to consider these two additional assessments:

- Ongoing high level of costs (especially for distribution channels);

- Slow increase of gross average returns (Gesamtverzinsung) since 2023 after a very long period of constant decrease for nearly 20 years .1

The basis for these statements will be outlined in the following paragraphs and tables.

Holding period

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | 7 years | 10 years | Whole reporting period | to... | |

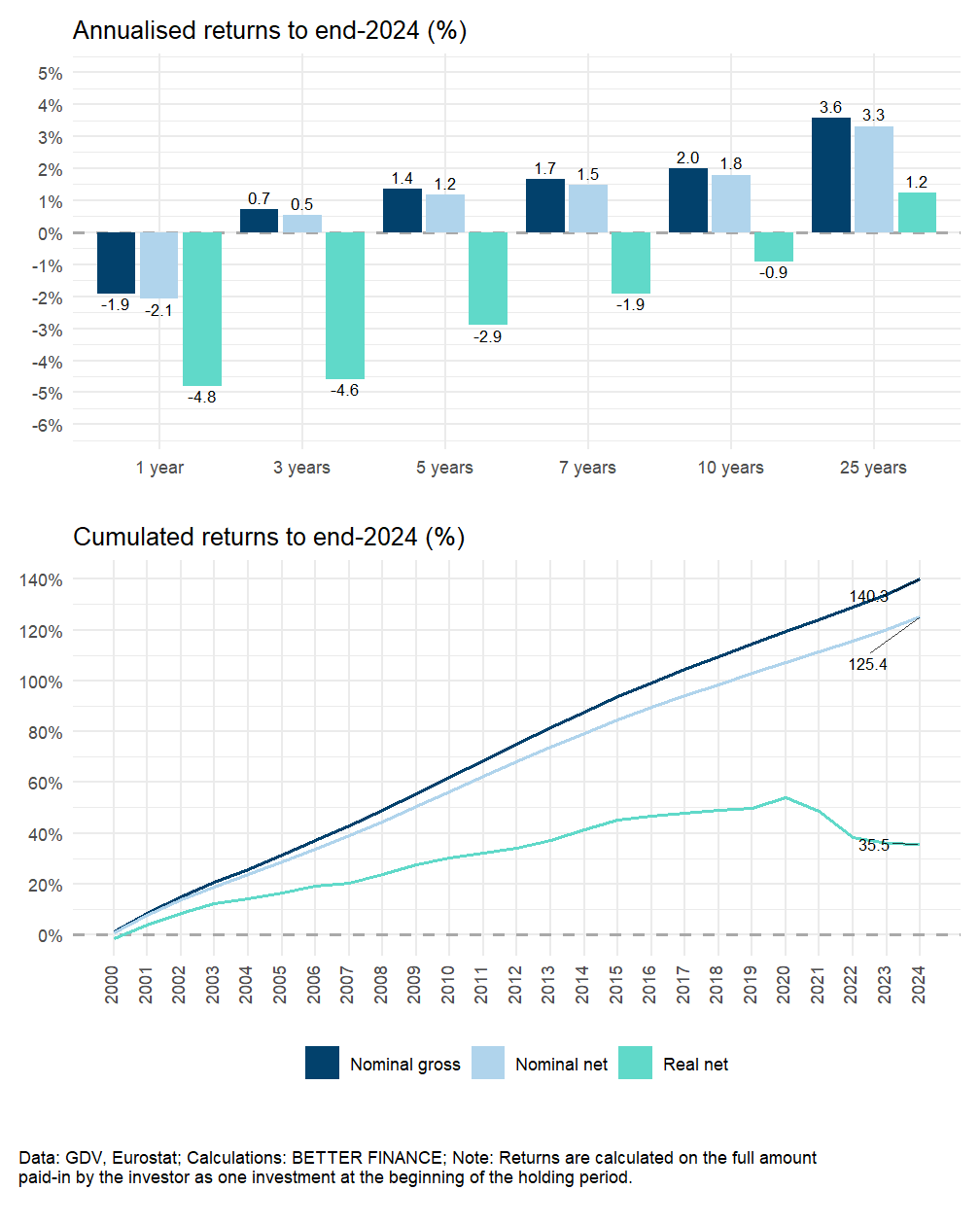

| Life insurances | -4.8% | -4.6% | -2.9% | -1.9% | -0.9% | 1.2% | end 2024 |

| Data: GDV, Eurostat; Calculations: BETTER FINANCE | |||||||

One of the major issues in the public debate on the reform of the pension system as a whole was the rise and subsequent stagnation of new business of the so-called Riester Pension. This particular state-subsidised private pension product was introduced in 2001 by the Federal Minister of Labour at the time to equalize some restrictions in the First Pension Pillar System established by the Federal Government. After a modest start, the Riester Pension experienced significant growth starting in 2005, primarily due to increased state allocations and changes in distribution remuneration rules. Another boost occurred in 2008 when not only annuity insurances, investment funds, and bank saving plans were admitted as pension products, but also a form of home loan savings plan known as Wohn-Riester.

By 2013, the threshold of 16 million contracts for all four categories of the Riester Pension had been reached, with approximately half of eligible employees participating and over 10 million insurance contracts issued. However, it soon became evident that there was no further growth in new business.

On the one hand, the increasingly persistent low-interest-rate environment of the 2010s was undoubtedly a major factor contributing to this stagnation, because the Riester Pension included a 100% minimum return guarantee on the gross premiums paid until the start of the payout phase. As a result, all product providers had to allocate a significant portion of their investments to fixed-income securities during the contribution phase, limiting their ability to fully capitalise on the booming stock markets during that period. On the other hand, there was an ongoing discussion on high costs, particularly concerning commissions for distributors, which did not stop.

All in all, it is fair to conclude that the Riester Pension was successful in terms of its social policy objectives. Low-income earners and families with children mostly benefited from direct state allocations, while high-income earners could profit from tax returns. However, neither the state authorities nor the different product providers and their distributors could dispel the widespread public scepticism regarding the real returns, with low benefits and high distribution costs during the accumulation phase, and lower amounts in the payout phase.2.

The result of these various contradictory developments was clear: the peak was reached in 2017 with 16.6 million contracts concluded, and from that year onwards, not only did new business stagnate, but there was a real loss in GWP and contracts (see the exact figures in Section 11.2). The proportion of contracts with premium exemptions increased to nearly 20%, and by 2024, the total number of contracts had now fallen even below the threshold of 15 million (exactly 14.97 million contracts). The public debate was increasingly dominated by the question “reform or abolishment” of the Riester Pension, and below, we will explore possible solutions that could be implemented.

11.2 Pension system in Germany: An overview

Germany belongs to those EU member states where the mandatory first pillar state pension system Gesetzliche Rentenversicherung (GRV) constitutes the most important part of the retirement provision. Therefore, occupational and private pension products primarily serve as additional retirement income sources. Besides these explicit pension products, for decades, home ownership (Immobilienbesitz) and asset allocation in securities, bank deposits, and so on (Vermögensbildung), have constituted the other non-insurance-based pillars of retirement provision (Altersvorsorge).

The GRV is supplemented by other pension regimes designed for specific professional groups (mostly self-employed) and employees of public administrations at the local, regional, and federal levels (first pillar bis pension systems). In 2005, through the reforms of the so-called Rürup-Kommission (see Section 12.3 on taxation) certain mechanism for adjusting the levels of mandatory contributions and payouts were introduced in order to cope with the impending long-term demographic changes.

But in the following years—regardless of the party collation in power at the federal level —additional social welfare legislation (including pension “add-ons” for mothers, the low-income sector, individuals with lengthy contribution histories, etc.) has led to nearly 25% of necessary contributions for first pillar pensions being funded by tax payers, amounting to nearly EUR 90 billion annually. The overall expenditure of the First Pillar Pension Scheme reached approximately EUR 381 billion in 2023. This places a significant financial burden on all taxpayers, and a financially sustainable solution has yet to be found, as the main demographic challenges are expected to have an increasingly significant impact from the mid-2020s onwards (for a detailed analysis of the reforms and counter-reforms of the GRV see Rentenversicherung 2025; German Council of Economic Experts, n.d. especially in 2016, chapter 7 and 2020, chapter 6).

With over 16 million occupational pension contracts, more than 18 million contracts for state-subsidised private pensions (Riester and Rürup pensions) and over 20 million private annuities in 2023 (for a total population of more than 80 million inhabitants) it is obvious that the insurance and pension sectors play a dominant role in voluntary retirement provision in Germany. This will be analysed more in detail in the following paragraphs, especially taking into consideration the strongly negative impacts of the low-interest-rate phase, mainly in the 2010s, and the risks of inflation from 2021/22 onward for the real returns of the future retirees and beneficiaries (see Deutsche Rentenversicherung 2021 for a general overview of state-subsidized and private pension plans; and Deutsches Institut für Altersvorsorge, n.d. for current analysis of private retirement provision, asset allocation and retail investor behaviour).

In November 2024 the “traffic light” coalition collapsed and after the general elections the new Federal Government based on a coalition of Christian and Social Democrats was established in May 2025. Related to the inevitable reform of pensions and retirement provision only slowly probable amendments were published (Tauber 2025). Related to Pillar I, the innovation of the former government, the so-called Generationenkapital (“Generational Capital”) will be reevaluated before any possible ongoing implementation. This new concept basically consists in a transfer of 10 bn Euro per year from 2024/25 on for at least 10 years by the federal budget to a newly founded public foundation. This foundation has to invest its capital in the global financial markets and to retransfer its gains to the First Pillar Pension System. The objective is to stabilize the obligatory pension contributions by employees and employers in the long term. 3 But no final decision has yet been taken by the new federal government.

In contrast to this, related to occupational pensions, the new government will probably adopt the proposals by the former government. Only minor legal changes were proposed in spring 2024 (like enlarged possibilities for companies to participate at a “pure Defined contributions (DC)” pension scheme even if they are not part of the initial collective agreement). “Zwischen Stärkung, Wurf und Abwarten” (2024).

Additionally a committee of experts from the government and external stakeholder groups, including insurers, investment companies, state consumer representatives and academics, was finally established in December 2022. The final report of this expert committee was published in July 2023 (see Bundesministerium für Finanzen 2023).

One of major recommendations from this expert committee is not to abolish the Riester Pension, but to reform it through several measures, some of which include the following: - Extension of eligibility to include self-employed individuals. - Greater flexibility for product providers and policyholders during the contribution phase, by reducing the impact of the minimum return guarantee. - Authorization of not only lifelong annuities but also temporary annuities during the payout phase. - Every citizen should have the possibility to establish a “private retirement account” into which they can consolidate all pension contracts eligible for state subsidies. - Independent comparison websites should be created to provide pre-contractual information on aspects such as risk diversification, guarantee models, costs, real returns, etc. In September 2024 a draft legislative act containing most of these proposals was published, but it was not adopted anymore due to the early general elections in February 2025. 4

Crucial part of the new coalition treaty of April 2025 is the introduction of the so-called “Early Start Pension” (Frühstartrente) and the “Active Pension” (Aktivrente), requested by the Christian Democrats. The “Early Start Pensions” mainly consists in a kind of individual retirement account for children in the age of 6 to 18 years (under the condition they go to school), for which the state transfers an allocation of 10 Euro per month. Life-insurances as well as exchange-traded funds (ETFs) may be chosen for this account, no pay-outs before the retirement age shall be possible, any other details are not yet fixed. The “Active Pension” shall be a strong tax incentive for those employees who reached the regular retirement age of 67 years and would like to continue to work. They shall benefit from a full tax relief up to 2000 Euro per month related to their ongoing regular income as employees in addition to the start of their payouts from the Pillar I pension which are taxed following to the Exempt Exempt Taxed (EET) principle. By giving this strong tax incentive to continue to work beyond the age of 67, the public debates on increasing the regular retirement age shall be made obsolete.

Additionally, in February 2021, the law for the new national digital PTS—Digitale Rentenübersicht—entered into force. This innovation aligns with similar initiatives in other EU member states that aim to provide citizens with an overview of all entitlements in the three basic pension pillars. After an initial trial phase, the PTS officially launched in June 2023 with a reduced number of participating institutions and companies, with plans for further continuous expansion.5

Only in subsequent editions of this “Will You Afford to Retire?” report will it be possible to analyse which of the recommendations from the expert committee for the reform of the Riester and other pension plans will be adopted, and to what extent the new digital pension tracking system is welcomed and used by the future retirees and current beneficiaries.

| Pillar I | Pillar II | Pillar III |

|---|---|---|

| Mandatory State Pension System (GRV) | Mostly voluntary occupational pension schemes | Voluntary individual annuities |

| All persons subject to social security charges contributed 18.7% of their gross income to the scheme | Employees have the right to a deferred compensation arrangement — employers have the right to choose the scheme | Mainly supplement of Pillars I and II Pension Plans |

| Source: BETTER FINANCE, own composition. | ||

11.3 Long-term and pension savings vehicles in Germany

With regard to occupational and private pension products, life-insurers are the most important institutional investors when compared to IORPs and investment funds companies. For 2024, the following total AuM figures for these institutional investors had been published Döring and Dungs (2025):

- Life-insurers: EUR 1012.4 bn;

- Pensionskassen (IORPs): EUR 211.0 bn;

- Pensionsfonds (IORPs): EUR 58.9 bn;

- Open Retail Investment Funds: EUR 1564 bn (without ETFs and real estate funds, December 2024).

The figure for life insurers includes “direct insurances” (pillar II), state subsidised private pension plans (Riester and Rürup pensions), and private annuities (pillar III). The main reason for this particularity is that German life insurers are not only authorised to consolidate all their assets under one common investment portfolio, notwithstanding the source of capital (premiums from policyholders, loans, credits, bonds, dividends, etc.) to build their technical reserves. Additionally separate compartments for technical reserves are obligatory only for partially or fully unit-linked products, one-off contribution products or purely biometrical products.6 Figure 11.1 illustrate the development of total AuM for life-insurers from 2000 to 2022:

These figures clearly show that despite two global financial market crises (in 2008/09 and in 2020), life insurers have been able to slowly but consistently grow their assets under management. This is partly due to the fact that many retail investors or policyholders still equate “security” with “guarantees”. In times of significant stock market downturns this may be an “experienced” attitude. However, it is also true that the “low for long” interest rate phase in the 2010s had a significant impact on the life insurers as well, as Table 11.4 shows.

| Year | Net interest rate |

|---|---|

| 2000 | 7.51% |

| 2005 | 5.18% |

| 2010 | 4.27% |

| 2011 | 4.13% |

| 2012 | 4.59% |

| 2013 | 4.68% |

| 2014 | 4.63% |

| 2015 | 4.52% |

| 2016 | 4.36% |

| 2017 | 4.49% |

| 2018 | 3.59% |

| 2019 | 3.92% |

| 2020 | 3.74% |

| 2021 | 3.57% |

| 2022 | 2.16% |

| 2023 | 2.27% |

| 2024 | 2.37% |

| Data: GDV – Die deutsche Lebensversicherung in Zahlen 2025, S. 28 („Nettoverzinsung der Kapitalanlagen“). | |

These tables show a strong ambiguity. On the one hand, life insurers achieved a constant growth of their assets under management (AuM) for many years which can be interpreted as a success of their reputation as institutional investors among retail investors and policyholders. Despite the gradual decline in net returns on their AuM, they have managed to maintain positive returns. From a consumer’s perspective, this may not seem highly detrimental, as long as inflation rates remained lower, but such a purely “nominal” view neglects the danger of “missed opportunities” for returns compared to stock markets.

This ambiguity has not gone unnoticed by an increasing part of retail policyholders, as evidenced by the fact that traditional life-insurance products based on guarantees lost their dominant position. Instead hybrid and unit-linked products, as well as products with reduced capital guarantees, have become more prominently important in new business. Of course, this shift was driven by life insurers themselves, because during the very low-interest-rate phase, especially in the second half of the 2010s, they sought to reduce the obligatory capital requirements linked to guarantees. This will be outlined more in detail in the next paragraph.

Second pillar: Implementation Types of Occupational Pension Plans

The main distinction of the German occupational pension system, in contrast to that of most other EU member states, is that the so-called IORPs do not play a dominant role. In the Netherlands, for example, IORPs like pension funds command a market share in occupational pensions of at least 70%, while the German IORPs (Pensionskassen and Pensionsfonds) together only reach a market share of about 25% in this pillar of retirement provision.

The reason for this difference is that three other “implementation types” of occupational pension plans have been dominant in the past and continue to play a significant role today: “book reserves” (or “direct pension commitments” / Direktzusagen) offered by employers, “support funds” (the oldest type of occupational pension saving institutions like mutual companies, often founded by the employers / Unterstützungskassen) and so-called “direct insurances” (Direktversicherungen) offered by life insurers and supported by a special tax regime for both employers and employees. IORPs such as Pensionskassen (PKs) and Pensionsfonds (PFs) only began to gain momentum from 2002 onward, following favourable changes to the tax regime. “Book Reserves” and “Support Funds” are not subject to the supervision of BaFin, but most of them reinsure their pension savings, and reinsurers are supervised by the NCA (for more details on the five “implementation types” of occupational pensions, see Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht 2012).

| Year | Direct insurances | Reinsured occ. Pensions | Pensionskassen | Pensionsfonds | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 5.83 | 1.80 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 8.10 |

| 2005 | 5.85 | 2.27 | 2.67 | 0.08 | 10.87 |

| 2010 | 6.75 | 2.76 | 3.38 | 0.32 | 13.21 |

| 2015 | 7.74 | 3.28 | 3.75 | 0.53 | 15.30 |

| 2016 | 7.89 | 3.34 | 3.74 | 0.47 | 15.44 |

| 2017 | 8.11 | 3.47 | 3.71 | 0.49 | 15.78 |

| 2018 | 8.37 | 3.52 | 3.69 | 0.52 | 16.10 |

| 2019 | 8.49 | 3.52 | 3.68 | 0.56 | 16.25 |

| 2020 | 8.57 | 3.58 | 3.63 | 0.60 | 16.38 |

| 2021 | 8.69 | 3.63 | 3.57 | 0.56 | 16.45 |

| 2022 | 8.80 | 3.65 | 3.48 | 0.61 | 16.54 |

| 2023 | 8.78 | 3.71 | 3.41 | 0.65 | 16.55 |

| 2024 | 8.81 | 3.72 | 3.33 | 0.68 | 16.55 |

| Data: Gesamtverband der Deutschen Versicherungswirtschaft e. V. (GDV) - Die deutsche Lebensversicherung in Zahlen 2025, S. 33, and previous years. | |||||

A little more than 30% of all employed persons in Germany are members of an occupational pension scheme (for more details, see Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales 2020, 2022).

| Year | Pensionskassen | Pensionsfonds |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2818.7 | 1836.5 |

| 2016 | 2724.3 | 1367.6 |

| 2017 | 2623.0 | 1515.5 |

| 2018 | 2495.2 | 756.4 |

| 2019 | 2406.4 | 1329.3 |

| 2020 | 2294.5 | 1038.3 |

| 2021 | 2237.9 | 1296.6 |

| 2022 | 2024.9 | 2231.1 |

| 2023 | 1923.1 | 1039.3 |

| 2024 | 1819.9 | 974.7 |

| Data: Gesamtverband der Deutschen Versicherungswirtschaft e. V. (GDV) - Die deutsche Lebensversicherung in Zahlen 2025, S. 34, and previous years. GWP of Direct Insurances are not disclosed separately.; Note: Figures are sometimes rectified in the following year. | ||

To some extent, the five different financing methods compete with each other,7 although it is also possible to combine two or more types. Both employers’ and employee’s contributions to occupational pensions are usually voluntary, mostly through a mechanism known as “salary conversion” or Entgeltumwandlung. However, employers have to offer at least a direct insurance pension contract, so that employees may benefit from tax advantages (deferred taxation) and savings on social security contributions if they choose to contribute. When there is a binding labour agreement, occupational pensions are generally organised for entire industrial sectors, and employees do not have the right to demand different occupational pension provisions. Many collective agreements also oblige employers to participate financially in occupational pension plans and restrict the employer’s ability to choose a different scheme. Occupational pensions are structured as deferred compensation, and contributions are subsequently exempt from taxation and social security contributions up to certain limits. This, in turn, reduces claims on the statutory first pillar pension system.

| Year | Pensionskassen1 | Pensionsfonds2 |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 86.2 | NA |

| 2006 | 92.6 | NA |

| 2007 | 98.9 | 13.4 |

| 2008 | 104.2 | 12.7 |

| 2009 | 107.9 | 16.3 |

| 2010 | 109.6 | 24.0 |

| 2011 | 115.8 | 25.0 |

| 2012 | 123.3 | 26.5 |

| 2013 | 131.0 | 26.6 |

| 2014 | 139.1 | 29.5 |

| 2015 | 147.7 | 29.4 |

| 2016 | 154.1 | 31.7 |

| 2017 | 162.2 | 32.4 |

| 2018 | 168.5 | 40.8 |

| 2019 | 176.9 | 45.5 |

| 2020 | 184.5 | 51.1 |

| 2021 | 192.9 | 54.0 |

| 2022 | 200.2 | 54.7 |

| 2023 | 206.1 | 58.7 |

| 2024 | 211.0 | 58.9 |

| 1 Pensionskassen: Mostly the rectified figures in the Annual Report of BaFin of the following year were taken. | ||

| 2 Pensionsfonds: AuM on behalf of employees and employers. | ||

Pensionskassen and Pensionsfonds fall under the category of and are regulated under Directive EU/2016/2341 (the “IORP Directive”). However, there is a unique aspect in the national supervisory insurance law: Pensionskassen (PKs) have the option to choose a different purely national supervisory regime, a choice mainly exercised by those PKs considered competitive IORPs (Wettbewerbs-Pensionskassen). This allows them to offer their pension plans to an unlimited number of employers, similar to specialised occupational pension insurers. Somewhat misleadingly, this option is called “deregulated” IORPs.

| Amount (EUR) | Men (%) | Women (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1000> | 17 | 3 |

| 500-1000 | 17 | 11 |

| 200-500 | 25 | 23 |

| <200 | 41 | 63 |

| Data: ABA, 2021; Calculations: BETTER FINANCE. | ||

These figures show that for nearly half of men and nearly two thirds of women, payouts from occupational pensions do not represent more than a small “add-on” to their first pillar pensions. Unfortunately, it is the national legislator itself that plays a significantly negative role in determining the effective payout amounts (cf. Chapter 12 on charges).

Similar to private annuities offered by life-insurers, occupational pensions, too, were largely dominated by pension schemes based on guarantees,8 and only the “low for long” interest rate phase of the 2010s could break this dogma at least partly. From 2018 onwards, a new law authorised so-called “Pure Defined-Contribution” pension schemes (Reine Beitragszusage), but it took another five years for collective agreements to be reached to implement at least three of these new pension plans, which can be offered by PKs, PFs or “direct insurances”.9

The persistent challenge of shifting away from the traditional mindset of equating “security” with “guarantees”, both among employers and trade unions as well as employees, remains a crucial task for broader financial education efforts aimed at promoting an “investment” or “shareholder culture” (Aktienkultur).

11.4 Third pillar: Private life-long annuities with and without state subsidies

In contrast to private lifelong annuities offered by life insurers, there are two categories of private pension products that are “certified” as eligible for specific state subsidies and which are therefore classified differently from a purely legal point of view:

- Rürup Pensions (which can be offered by life insurers and investment companies): Pillar I.

- Riester Pensions (which can be offered by life insurers, investment companies, banks and real estate loan and savings institutions): Pillar II.

For the sake of simplicity, we have included them in the chapter on the third pillar private pensions, which can be justified because the main contributors are retail investors and policyholders.

The main reason Rürup Pensions are legally classified as belonging to Pillar I pensions is the stringent framework they operate within, especially with regard to the payouts. Contributions are allocated for monthly life-long annuities, starting with the retirement phase at the age of 62 (or at the age of 60 for contracts concluded before 2012), and there is no possibility of lump-sum payments. The benefits are personal, thus non-transferable, and cannot be disposed of or converted into capital.

Rürup pensions, specifically designed for self-employed individuals and freelancers who were not eligible for state-supported pension savings before its establishment, are advantageous for those with higher revenues because of the high tax-exempt savings amount. They take the form of annuity contracts that are, in contrast with Riester, non-redeemable. It is also possible to subscribe to Rürup pension contracts that invest in investment funds through savings plans. Such contracts can be designed with or without capital guarantees.

Rürup Pensions were introduced in 2005. Table 11.9 shows the number of concluded contracts from inception to the present day.

| Year | Nb. of contracts |

|---|---|

| 2005 | 0.148 |

| 2010 | 1.277 |

| 2015 | 1.975 |

| 2020 | 2.386 |

| 2021 | 2.477 |

| 2022 | 2.574 |

| 2023 | 2.703 |

| 2024 | 2.817 |

| Data: GDV – Die deutsche Lebensversicherung in Zahlen 2025, S. 14. | |

Rürup pensions receive subsidies from the state exclusively through broad tax exemptions during the contribution phase. For more details on these particular provisions, please refer to the chapter on taxation below.

In contrast to Rürup Pensions subscribers of Riester pension plans receive state subsidies through both direct allocations and tax reimbursements when certain thresholds are met. The amount received depends on personally invested contributions. Allocations are at their maximised when the total contributions to a Riester product (that is, personally invested contributions plus allocations) reach at least 4% of the individual’s previous year’s income, up to a maximum of EUR 2100.

The allocations add up to EUR 175 per adult (according to the pension law of summer 2017), plus EUR 300 for each child born since 2008 and EUR 185 for those born before 2008. Subscribers that are younger than 25 receive a bonus of up to EUR 200 at the moment of subscription to a Riester product. The minimum contribution to receive the full allocations is EUR 60 per year. If the calculated minimum contribution for a low-income earner is less than EUR 60, this minimum contribution of 60 euros must nevertheless be paid in order to receive full support. If an individual contributes less than their minimum requirement (4% of the previous year’s income, with a maximum of EUR 2100, minus any applicable allocation, but at least EUR 60 per year), their subsidies are reduced proportionately.

Riester pension benefits can be paid out starting at the age of 62, or at the age of 60 for contracts concluded before 2012. Subscribers have the option to convert the invested capital into a life annuity, or choose a programmed withdrawal, where up to 30% of the accumulated savings can be paid out as a lump-sum. Furthermore, at least one fifth of the accumulated savings is reserved for life annuities starting at the age of 85. For more details on all these specific provisions, please refer to the chapter on taxation below, with additional references.

As already pointed out in the Introduction, four types of pension products are allowed for Riester pension plans:

- Bank savings plan (Banksparplan): These contracts are typical long-term bank savings plans with fixed or variable interest rates.

- Annuity contract (Rentenversicherung): These Riester plans, offered by insurance companies, come in three forms. There are traditional annuity contracts with guaranteed returns and additional bonuses. Additionally, there are hybrid contracts where a part of the retirement savings is invested in investment funds. They consist of both a guaranteed part and a unit-linked part that depends on the performance of the investment funds.

- Investment fund savings plan (Fondssparplan): Savings are unit-linked and invested in investment funds chosen by the subscriber from a pool of funds proposed by a financial intermediary or the investment company. The intermediary or the investment company has to at least guarantee that the invested money, along with the state’s subsidies, are available at the time of retirement. In the case of premature withdrawals, a loss of capital is possible.

- Home loan and savings contract (Wohn-Riester/Eigenheimrente): These contracts take the form of real estate savings agreements. This is the most recent type of Riester scheme and is based on the notion that rent-free housing at old age is a sort of individual retirement provision comparable to regular monetary payments.

Riester pension plans were introduced in 2001. Table 11.10 shows the number of concluded contracts from inception to the present day.

| Year | Annuity contracts | Bank savings plans | Investment fund savings plans | Home loan and savings contracts | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 1 400 | — | — | — | 1 400 |

| 2002 | 2 998 | 150 | 174 | — | 3 322 |

| 2003 | 3 451 | 197 | 241 | — | 3 889 |

| 2004 | 3 557 | 213 | 316 | — | 4 086 |

| 2005 | 4 524 | 260 | 574 | — | 5 358 |

| 2006 | 6 388 | 351 | 1 231 | — | 7 970 |

| 2007 | 8 194 | 480 | 1 922 | — | 10 596 |

| 2008 | 9 285 | 554 | 2 386 | 22 | 12 247 |

| 2009 | 9 995 | 634 | 2 629 | 197 | 13 455 |

| 2010 | 10 484 | 703 | 2 815 | 460 | 14 462 |

| 2011 | 10 998 | 750 | 2 953 | 724 | 15 425 |

| 2012 | 11 023 | 781 | 2 989 | 953 | 15 746 |

| 2013 | 11 013 | 805 | 3 027 | 1 154 | 15 999 |

| 2014 | 11 030 | 814 | 3 071 | 1 377 | 16 292 |

| 2015 | 10 996 | 804 | 3 125 | 1 564 | 16 489 |

| 2016 | 10 931 | 774 | 3 174 | 1 691 | 16 570 |

| 2017 | 10 881 | 726 | 3 233 | 1 767 | 16 607 |

| 2018 | 10 827 | 676 | 3 288 | 1 810 | 16 601 |

| 2019 | 10 773 | 627 | 3 313 | 1 818 | 16 531 |

| 2020 | 10 687 | 592 | 3 297 | 1 793 | 16 369 |

| 2021 | 10 672 | 546 | 3 263 | 1 730 | 16 211 |

| 2022 | 10 514 | 529 | 3 200 | 1 650 | 15 893 |

| 2023 | 10 254 | 511 | 3 153 | 1 593 | 15 511 |

| 2024 | 9 898 | 499 | 3 062 | 1 515 | 14 974 |

| Data: Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (BMAS website). | |||||

These figures clearly demonstrate what was already outlined in the Introduction: the most important “breakthrough” in Riester pension plans took place from 2005 to 2011, when allocations had reached their final highest levels, and additional real estate savings plans were introduced. Subsequently, the public debate on costs and low returns intensified,10 resulting in a decline in new business, which nearly came to a complete stop from 2018 onwards. The future of Riester pension plans will hinge on the implementation of innovations recommended by the new expert commission of the Federal Ministry of Finance in July 2023.

Besides these state subsidised private pension plans, there is a substantial market for life insurances and private annuities that have benefited from special tax regimes established for decades. In the following chapter on taxation, we will delve into the significant impacts of the fundamental change in the tax regime to deferred taxation for all pension pillars since 2005. First, however, we will focus on the quantitative changes amongst the various categories, differentiating between traditional life insurance and life-long annuities, as already indicated in the Introduction.

In Germany the main distinction between life insurances and “annuity insurance” (Rentenversicherungen) lies in their coverage of different biometric risks: Life insurance covers the death risk (with a fixed insured sum) while annuities cover the risk of longevity (through a life-long pension). Of course, it is possible to combine the two biometric risks: life insurances usually offer (at the end of the accumulation phase) the choice between a lump sum payout or a life-long pension (Kapitalwahlrecht), and the same applies to deferred annuity contracts, that include the accumulation phase (in contrast to “immediate annuities” Sofortrenten based on a lump sum contribution).

When a policyholder of an annuity chooses the life-long pension option, it is mostly possible to include a period during which the pension will be paid to another person fixed in the contract, in case the policyholders dies shortly after the beginning of pension payouts (usually this period is limited to ten years: Rentengarantiezeit).11 As the inclusion of a Rentengarantiezeit will increase the calculated costs of the biometric risk coverage, in consequence the payouts for the annuity will be reduced proportionately.

Additionally, there are pure risk or term life insurances (Risiko-Lebensversicherungen) that solely cover the risk of death without including an investment component in the premium. Usually these contracts are concluded for a fixed period, and if the insured loss (i.e. the death risk) does not occur, there are no payouts either during the term or at the end of the contract period.

Table 11.11 displays, based on statistics from GDV, long-term trends in the number of contracts among life insurances, annuities, and term life insurances.

| Year | Life-insurances (%) | Annuities (%) | Term life-insurances (%) | Total number of contracts (mln.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 72.0 | 12.0 | 16.0 | 87.6 |

| 2005 | 58.6 | 26.1 | 15.3 | 94.2 |

| 2010 | 47.5 | 38.9 | 13.6 | 90.5 |

| 2015 | 38.1 | 46.7 | 15.2 | 86.7 |

| 2020 | 28.2 | 55.1 | 16.7 | 83.4 |

| 2021 | 26.7 | 56.8 | 16.5 | 82.7 |

| 2022 | 25.2 | 58.4 | 16.4 | 81.8 |

| 2023 | 24.0 | 59.1 | 16.9 | 81.4 |

| 2024 | 22.8 | 60.4 | 16.8 | 80.3 |

| Data: GDV – Die Deutsche Lebensversicherung in Zahlen 2025, S. 16 (Tabelle: Lebensversicherung – Bestand an Hauptversicherungen, Anzahl der Verträge). | ||||

The most notable change that can be observed is the slow, but constant loss of market share of traditional “capital life-insurance”. Their market share of new business (in terms of the number of contracts) was only 7.0% in 2022, the lowest figure ever recorded (due to the rise of interest rates this market share increased to 7.4% in 2023, but in 2024 fell back again to 7.0%). This is in stark contrast to annuities which grew up to represent 47.9 % of all life-insurance categories (in 2024). Within the annuities category, unit-linked products had a market share of 15.0%, hybrid products or those with reduced guarantees accounted for 27.2% and products with classical guarantees constituted 5.7 %. In contrast to these growing figures, pure unit-linked life-insurances reached a market share of only 2.0 % in 2024. These figures clearly show that German policyholders shifted away from traditional 100% capital guarantees whilst also avoiding full capital market risks without any guarantees (Gesamtverband der Versicherer 2025, 10–11).

12 Charges

Germany belongs to those EU member states in which the commission-based distribution channels for life-insurances as well as for all other insurance classes are the most important ones. Unfortunately the publicly available figures do not show the real impact of these charges on pensions on the level of the product category in a transparent way. Prospective policyholders or beneficiaries are, of course, informed about the total distribution costs through various pre-contractual information documents when they have selected a particular pension product from pillar II or III.

12.1 Charges of occupational pensions

Related to occupational pensions acquisition fees are mainly relevant for “direct insurances” and so-called “competitive” IORPs. Since “direct insurances” are offered by life-insurers, costs are usually lower than the average figures for life-insurers outlined in this paragraph below (mainly due to collective contracts with the employer, which differ in each particular case). In contrast to most Pensionskassen, so-called “competitive” IORPs (Wettbewerbs-Pensionskassen) may offer their contracts to an unlimited number of employers or sponsors. According to BaFin in 2021, there were about 20 “competitive” out of a total of 134 Pensionskassen.

While the lack of comparability at the level of product categories is a concern,12 this does not mean that prospective and ongoing members and beneficiaries of these IORPs are not informed about acquisition and administration costs by the product providers. The national legislator has established strict provisions regarding the disclosure of costs based on EU regulations (IORP II Directive) and additional national supervisory laws (as well in the pre-contractual information documents as during the contribution and/or pay-out phases by the Pension Benefit Statements, and in the annual business reports).

12.2 Charges of life insurances: The burden of commissions

Unfortunately, the most important burden on beneficiaries of occupational pensions is imposed by the national legislator: in 2004, the Social Democrat Minister of Health introduced mandatory contributions from beneficiaries of occupational pensions to public health insurance. These mandatory contributions reduce the payouts by about 15% (only monthly payouts up to EUR 187.25 in 2025 are exempted). Many actions have been taken against this law, but no federal government, regardless of the party coalition in power, has revised this law until now. This conflict can be considered a fundamental conflict between two pillars of the social security system (health versus pensions), with health as the “winner” over pensions.

Table 12.1 shows that there seems to be—in total—a slow, but constant decrease of the burden of acquisition and administration fees over the last 20 years

| Year | Acquisition fees1 | Admin. and mgt. fees |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 5.60% | 0.40% |

| 2001 | 5.50% | 0.39% |

| 2002 | 5.40% | 0.38% |

| 2003 | 5.00% | 0.37% |

| 2004 | 4.50% | 0.35% |

| 2005 | 5.60% | 0.35% |

| 2006 | 4.90% | 0.33% |

| 2007 | 5.20% | 0.31% |

| 2008 | 4.90% | 0.30% |

| 2009 | 5.20% | 0.29% |

| 2010 | 5.10% | 0.27% |

| 2011 | 5.00% | 0.25% |

| 2012 | 5.00% | 0.25% |

| 2013 | 5.10% | 0.24% |

| 2014 | 5.00% | 0.23% |

| 2015 | 4.90% | 0.22% |

| 2016 | 4.80% | 0.21% |

| 2017 | 4.70% | 0.20% |

| 2018 | 4.60% | 0.20% |

| 2019 | 4.40% | 0.19% |

| 2020 | 4.50% | 0.18% |

| 2021 | 4.50% | 0.18% |

| 2022 | 4.70% | 0.18% |

| 2023 | 4.50% | 0.18% |

| 2024 | 4.40% | 0.18% |

| 1 % of premiums | ||

| Data: GDV Calculations: BETTER FINANCE. | ||

| Note: Acquisition fee figures are taken from GDV, but we should note that GDV’s calculation departs from the standard APE calculation and most likely underestimate actual acquisition costs borne by policyholders. | ||

But this impression of a slow but constant decrease in the total sum of charges is somewhat misleading from a consumer perspective, because, unlike retail investment funds, life insurers do not rely solely on the ongoing premiums of policy holders. As shown in Figure 12.1, life insurers have access to a wide range of diverse sources of income (for example, life insurers are issuers of their own corporate bonds), which are all included in the total amount of AuM.

Therefore, usually, acquisition fees of life insurers are calculated in relation to the GWP for new business each year, while ongoing administrative fees are determined based on the total premiums earned each year. These percentage figures are shown in Table 12.1. But these percentage figures do not disclose the real cost problem of life-insurers. By looking at the absolute amounts of these costs, displayed in Table 12.2, it becomes obvious that over the last 20 years, acquisition fees have consistently been three to four times higher than administration fees.

| Year | Acquisition costs (EUR bln.) | Administration costs (EUR bln.) |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 6.696 | 2.143 |

| 2005 | 7.323 | 2.305 |

| 2010 | 7.987 | 2.100 |

| 2011 | 8.392 | 2.016 |

| 2012 | 8.140 | 2.032 |

| 2013 | 7.427 | 2.012 |

| 2014 | 7.643 | 2.014 |

| 2015 | 7.162 | 2.040 |

| 2016 | 7.055 | 1.989 |

| 2017 | 6.840 | 1.995 |

| 2018 | 7.037 | 2.027 |

| 2019 | 7.540 | 2.035 |

| 2020 | 7.720 | 2.075 |

| 2021 | 8.349 | 2.107 |

| 2022 | 7.986 | 2.223 |

| 2023 | 7.893 | 2.220 |

| 2024 | 8.039 | 2.190 |

| Data: GDV – Die deutsche Lebensversicherung in Zahlen 2025, S. 29 (and previous editions) (Tabelle: „Kostenquoten der Lebensversicherung“).. | ||

The conclusion is clear: the commission-based distribution channels are the real cost drivers for life-insurers. In 2022 and 2023, the reduction of the total amount of acquisition costs (in absolute figures) is simply due to the fact that new business sharply declined (compared to 2021; measured as a percentage of GWP of new business the figures are stable). In 2024 the absolute total amount of acquisition costs increased again (even beyond the threshold of 8bn Euro), whilst the percentage figure dropped by only one basic point - so again, no substantial change.

Additionally, it is worth noting that GDV only discloses the total sums for these costs, rather than detailed figures for the various product categories such as occupational direct insurances, state-subsidised Riester and Rürup pensions, or private classical, unit-linked and hybrid annuities. While there are many costs and returns analyses conducted by scientific institutes, private rating agencies, economic and financial magazines, and Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (2022a), these figures are not regularly published. To compare calculated costs, one must rely on pre-contractual Key Information Documents (KIDs) (based on EU regulations for private life insurances and annuities), or the Produktinformationsblatt (PIB), pre-contractual based on national legislation, for Riester and Rürup pension contracts, similar to occupational pensions.

12.3 Taxation

In 2002, the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) took the fundamental decision to force the legislator to introduce “deferred taxation” as the new system for pension taxation. This new system exempts contributions from taxation and taxes only the pay-outs, changing the system fromTaxed Exempt Exempt (TEE) (vorgelagerte Besteuerung) to EET (nachgelagerte Besteuerung). This fundamental change had to be applied to all three pillars of the pension system. As a result, the federal government established a scientific committee under the leadership of Finance Professor Bert Rürup (Rürup-Kommission). This commission worked out the details and presented its report in 2003. Due to this crucial reform, which entered into force in 2005, life insurances lost their unique privilege of non-taxed lump sum payouts, which constituted one of the major reasons for their overwhelming success in distribution practices up to that year.

| Product categories |

Phase

|

Fiscal Regime | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contributions | Investment returns | Payouts | ||

| Life insurances | Exempted | Exempted | Taxed | EET |

| Source: BETTER FINANCE own elaboration, based on German tax authority. | ||||

First pillar pensions

Following the proposals of the Rürup-Kommission, a transitional period of 35 years began in 2005 to implement the shift from the TEE to the EET regime. In 2005, for all pensions which started that year, 50% of the total payout amount was taxed at the individual tax rate. This percentage of the total payout amount subject to taxation increased by 2% each year until 2020, and from 2020 onwards by 1% per year, in order to reach 100% of the payouts in 2040 for new pension recipients each year. For reasons of social justice, there is a downward cap to exempt low pensions from any taxation (Rentenfreibetrag). At the same time there is an algorithm to reduce the taxation of mandatory contributions to the pensions system over time (for more details on the taxation system, see Deutsche Rentenversicherung, n.d.).

Occupational pensions (Pillar II)

Payouts from Pensionskassen and Direct Insurances which started before 2005 typically remain exempt from any taxation (at least five years of contributions and a twelve-year contract duration). Payouts from any kind of implementation type of occupational pension plans that started in 2005 or later are fully taxed based on the individual tax rate.

Contributions to all five “implementation types” of occupational pensions are exempt from mandatory contributions to the social security system up to a certain limit (in 2025, this limit is set at EUR 3864 as Beitragsbemessungsgrenze: this limit represents 4% of the income up to which employees have to pay mandatory contributions to the First Pillar Pension System). The double of this amount, which in 2025 is EUR 7728, is exempt from taxes when making contributions to PK, PF and Direct Insurances. Additionally, there is even a full exemption from taxes without any limit for contributions, if these are made for book reserves or support funds (for more information, see Deutsche Rentenversicherung, n.d.).

Private Pension Plans state subsidised (Riester and Rürup Pensions)

Following the principle of deferred taxation (EET) contributions are exempt from taxes up to certain limits. For Riester pension plans, the maximum limit is EUR 2100 per year (or 4% of the personal gross income per year for lower incomes). For Rürup pension plans this maximum limit is much higher (in 2025 up to EUR 29 343 , which is linked to a special regulation of the first pillar pension system).

In the payout phase both types of these state subsidised private pension plans are fully subject to the individual taxation rate (for more information see Bund der Versicherten, n.d.).

Life-insurances and private annuities

Contributions are no longer tax-deductible as special expenses and have to be made from taxed income. The benefits of life insurances (i.e. the difference between contributions and total pay-outs) are taxed during the retirement phase at the general tax rate of 25% (like for all investment returns), but there are some limited possibilities to recover a portion of these taxes through the individual yearly tax declaration.

Furthermore, it is important to differentiate between whether the insurance benefit is provided as a one-time lump-sum payment or if a lifetime annuity payment is chosen. In the case of lump-sum payouts, if the contract has been in force for at least 12 years and the insured is older than 60 years, or 62 years (for contracts subscribed to after 31 December 2011), only 50% of the earnings are subject to taxation (Halbeinkünfteverfahren). If these conditions are not met, the full earnings are taxed.

In the case of private life-long annuities, additional tax relief is possible, depending on the age of the first retirement payout, as outlined in the tax table. For instance, if the retiree is 60 years old, 22% of the earnings are subject to taxation, and at the age of 65 only 18% (Ertragsanteilbesteuerung, for more information on the tax regime for life insurance and private annuities, see Leine 2023).

12.4 Performance of German long-term and pension savings

Real net returns of German long-term and pension savings

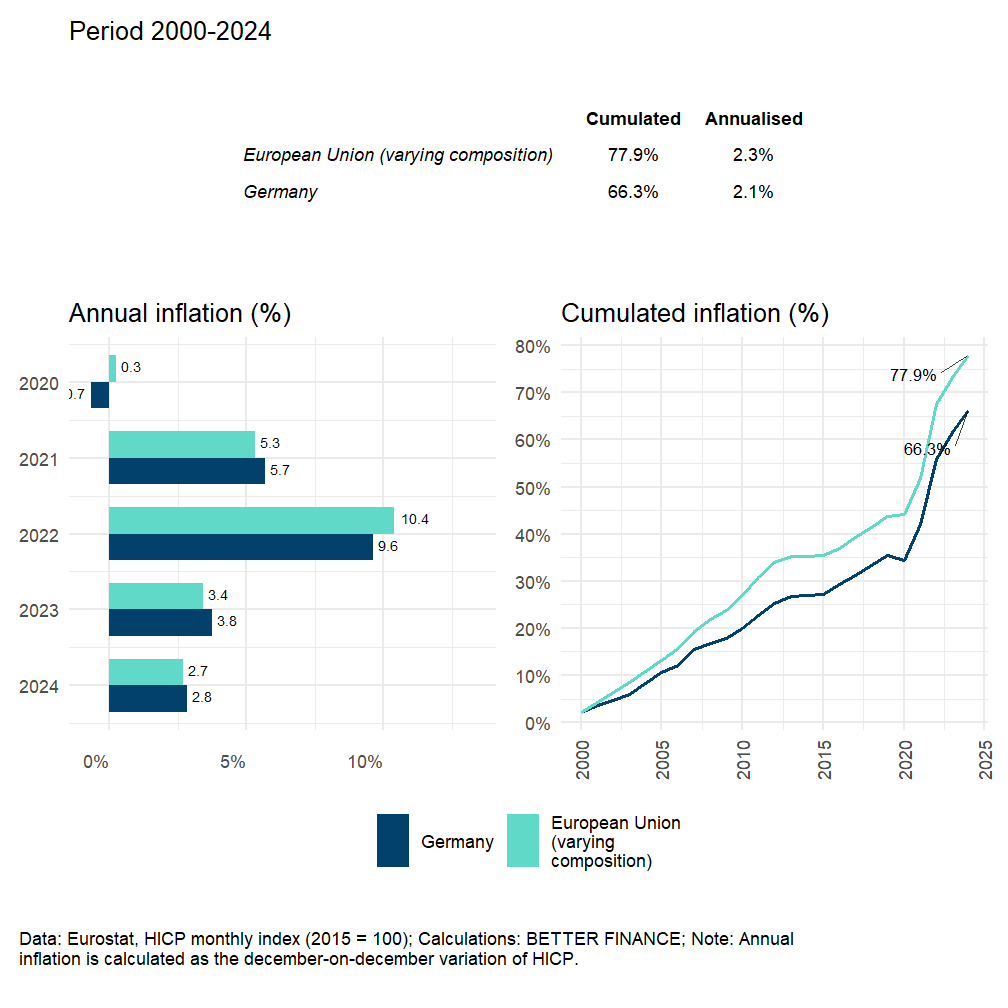

When examining the inflation figures in Germany (see Figure 12.2), it is obvious that for a very long time—especially during the first decade after 2000—inflation rates were at most as high as the EU average, often even lower. However, a dramatic change started in 2021. Germany does did not belong to those EU member states most severely affected by the sudden and sharp rise in inflation rates (like the Baltic countries for example), but there are were specific national reasons for the inflation increase exceeding the EU average. In 2021/22, the main reason was the full impact of the rise of energy prices caused by the strong dependency on petrol and gas from Russia, which had to be replaced after the onset of the Russian war against Ukraine in February 2022. In response, the Federal Government decided to help private households with substantial additional allocations in order to mitigate the direct impacts of this sudden price “attack” on family finances. In 2023 inflation strongly decreased in comparison to 2022, and the main driver of inflation shifted to food costs. In second place, the increasing salaries of employees in certain industry and artisan sectors, partly supported by trade union demands, are additional drivers of inflation. In 2024 the inflation rate fell again to 2.8% and was even a little bit below the average inflation rate of the EU (2.7%) and of Euro-Zone (2.4%). (Siedenbiedel 2023; Statistisches Bundesamt n.d.).

Regarding life insurances and pensions, the opposing effects of inflation and rising interest rates on assets are clear: with regard to fixed-income securities, “hidden reserves” may diminish or even reach negative market values, while new investments will yield higher returns but only in the very long run. This perspective was clearly outlined by Frank Grund, the BaFin Executive Director for Insurances, in a public speech in November 2022 (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht 2022b). However, by December 2022, it became obvious that some of the major life insurers reversed their approach and began increasing the bonuses for their products for the first time since the early 2010s (VersicherungsJournal Deutschland 2022; Assekurata Ratings 2022, 2024).

Looking at the annual performance of the life insurances displayed in Figure 12.3, it is clear that charges alone have consistently reduced the nominal return by a quarter to a third over the last twenty years. This fact can only be described as having a severe detrimental impact on the policyholders’ stakes. It supports the conclusions already outlined in the chapter on charges, especially distribution charges, above.

Table 12.4 shows the specific of acquisition costs over varying holding periods, based on our scenario of a single initial investment at the beginning of the period. The negative effect on returns is felt particularly strongly on shorter periods (-1.5 percentage point (p.p.) for the 3-year period 2022-2024) but progressively fades with each passing year of positive financial return, falling to -0.2 p.p. over the period 2000-2024.

Return on full contribution (paid-in amount)

|

Return on invested assets (contribution minus entry fees)

|

Effect of entry fees on return (percentage points)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annualised | Cumulated | Annualised | Cumulated | Annualised | Cumulated | |

| 1 year (2024) | -4.8% | -4.8% | -0.4% | -0.4% | -4.4pp | -4.4pp |

| 3 years (2022-2024) | -4.6% | -13.1% | -3.0% | -8.9% | -1.5pp | -4.3pp |

| 5 years (2020-2024) | -2.9% | -13.7% | -2.0% | -9.6% | -0.9pp | -4.1pp |

| 7 years (2018-2024) | -1.9% | -12.6% | -1.2% | -8.4% | -0.7pp | -4.2pp |

| 10 years (2015-2024) | -0.9% | -8.8% | -0.4% | -4.1% | -0.5pp | -4.7pp |

| 25 years (2000-2024) | 1.2% | 35.5% | 1.5% | 43.6% | -0.2pp | -8.1pp |

| Data: GDV. | ||||||

Additionally, in contrast to former periods of inflation (for ex. in the 1970s), in 2022 and 2023 there was now an ongoing strongly negative difference between the level of inflation in Germany and the level of the European Central Bank (ECB) Key Interest Rate, even though the latter has been raised up to 4.5% in September 2023. Some economists referred to this situation as “financial repression” (on this topic, see, e.g., BETTER FINANCE 2022). Fortunately this overall picture has considerably improved since mainly due to the sharply decreasing inflation and stabilized, even somewhat – at the same time - reduced key interest rates (the latter down to 2% in June 2025 by the ECB).

As a consequence, as long as fixed-income securities remain a major part of the asset allocation for life insurers and pension funds, there is a substantial risk of a substantial loss of purchasing power for policyholders over the long term, even though some life insurers have made minor increases in bonuses. This long-term erosion of purchasing power will persist, even if inflation does not remain at its current very high levels.

The negative effects of inflation may be mitigated for certain beneficiaries of occupational pensions provided by Pensionskassen and Pensionsfonds. Some of these pensions scheme include a clause that obliges sponsors to increase their contributions in response to the ongoing inflation rate. Unfortunately, BaFin does not publish any figures regarding the number of IORPs that offer this contractual clause.

Do German savings products beat capital markets?

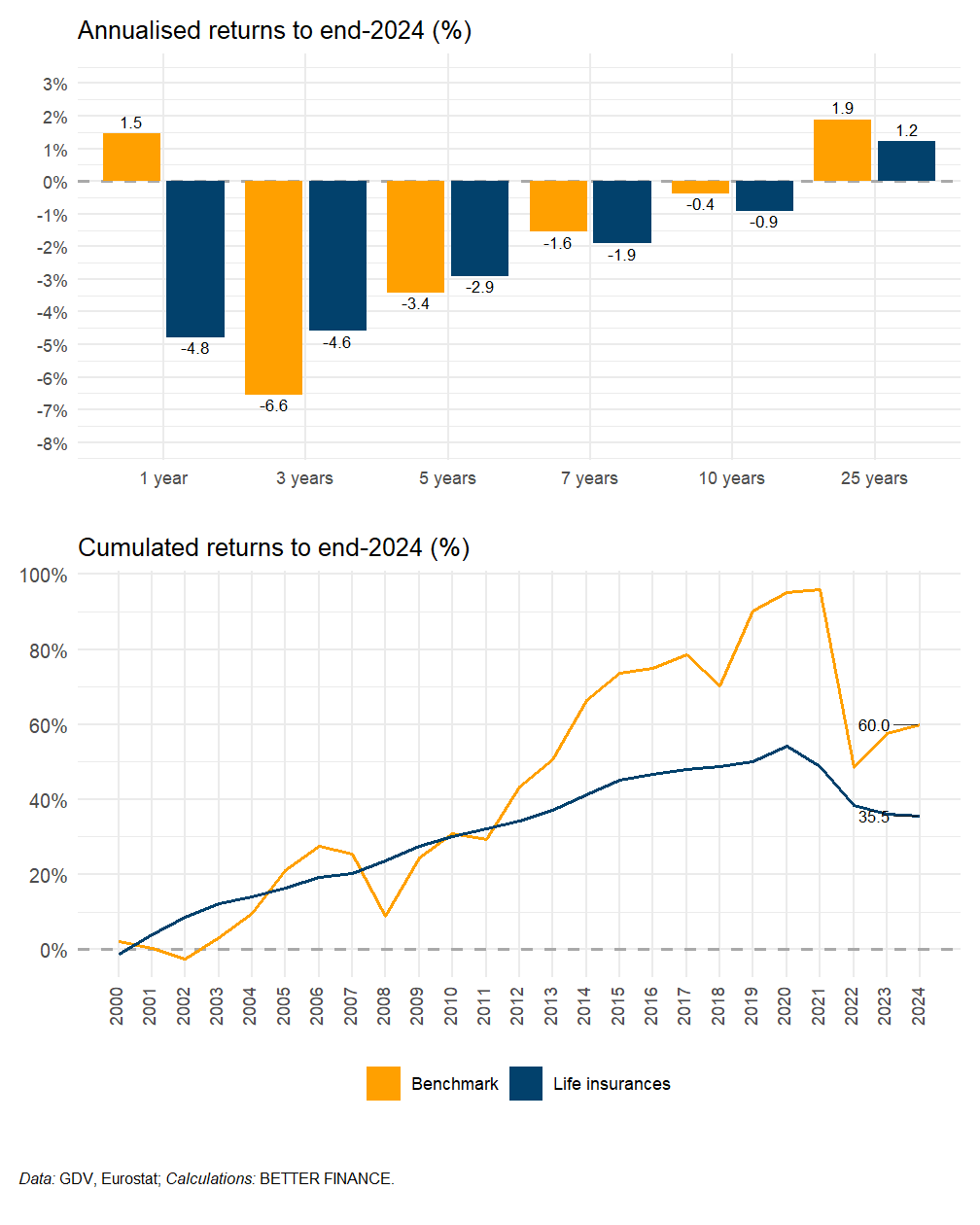

Figure 12.4 shows the comparison of the performance of life insurers with a balanced benchmark portfolio, the composition of which is presented in Table 12.5. Since capital guarantees during the accumulation phase play a dominant role in the German life-insurance market, we have selected a benchmark portfolio comprising 30% equities and 70% bonds.

| Equity index | Bonds index | Start year | Allocation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life insurances | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2000 | 30%–70% |

| Data: STOXX, Bloomberg; Note: Benchmark porfolios are rebalanced annually. | ||||

If this portion is changed by increasing the proportion of equities, the results are less favourable for the life insurers due to the higher “risk benefit” of the benchmark:

- 30/70: Cumulated returns of the benchmark 2000-2024: 59.96% (i.e., 12.63 p.p.. below the 50/50 benchmark), 24.42 p.p. above the cumulated returns of life insurance contracts.

- 40/60: Cumulated returns of the benchmark 2000-2024: 66.88% (i.e., 6.92 p.p. below the 50/50 benchmark), 31.34 p.p. above returns of life insurance contracts.

- 50/50: Cumulated returns of the benchmark 2000-2024: 72.59%, 37.05 p.p. above the cumulated returns of life insurance contracts.

When assessing the return comparison, it’s important to consider not only guarantees but also other specific insurance factors. We will outline some fundamental aspects such as life insurance as a “complex” product in itself, the emerging trade-off between “guarantees” and “security”, and the necessary combination of the accumulation phase and decumulation phase for payouts.

When stating that life insurances are “complex” products in themselves, this implies that the “complexity” is not only linked to the mechanisms of the investment part of the premium but also with the “insurance wrapper” (European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority 2022, 90–106). In terms of costs that reduce the investment component of the total gross premium, it is essential to consider not only distribution and administration costs, but also biometric costs (for example, whether death risk is included or not).

The death risk can be covered both during the accumulation phase and the decumulation phase, whereas coverage for the risk of longevity is relevant only for the decumulation phase. We will come back on this second point later.

It is important to emphasize that any comparison of returns for life insurances can only be related to the investment part of the premium, not to the gross premium paid by the policyholder.13 Therefore the transparent disclosure of the investment part of the gross premium by life insurers constitutes one of the fundamental “classical” demands by German consumer protectors (Prämientrennung—differentiation of gross premium into three parts: investment part, distribution and administration costs, and costs of biometric risk coverage).

The issue of a potential conflict between the “guaranteed interest rate” (Garantiezins) included in a life insurance contract and the general promise of “security”, especially during the accumulation phase, only emerged during the “low for long” interest rate phase. As long as the “guaranteed interest rates” were between 4% (in 2000) and 2.25% (in 2010) in the first decade after 2000, and the total benefits (Gesamtverzinsung including capital guarantees and bonuses) averaged around 7% in 2000 and 4% in 2010, life insurance could be considered as a “security” against the turbulences of global capital markets (especially during the two global financial crises in 2000/01 and in 2008/09).

However, this perception changed dramatically during the “low for long” interest rate phase throughout the 2010s, when the authorised maximum “guaranteed interest rate” dropped to 0.9% in 2017 and further to only 0.25% in 2022 (and the average total benefits of life insurers to 2.23% in 2020 (see Deutsche Aktuarvereinigung 2023; Walz 2020)). Following a recommendation of the Deutsche Aktuarsvereinigung (DAV), the German association of actuaries, the Federal Ministry of Finance decided in April 2024 that this interest rate shall had again to be increased up to 1% from January 2025 onwards (see Gesamtverband der Versicherer 2024, “Increase of maximum interest rate is an appropriate reaction…”).

As already outlined in the previous chapter the consequences were clear: life insurers as well as policyholders broadly said “good-bye” to guarantees and accepted the fundamental change to products with more or less strongly reduced guarantees during to accumulation phase. It was shown by actuarial studies that reduced guarantees could help to increase at least nominal returns, even though the real results were and are still rather modest.

Even though it is a statistically proven general factor that life-expectancy and in consequence longevity are increasing slowly but constantly, in Germany there is the particular constellation that neither the average life-expectancy of the total population nor even the mortality tables of the association of actuaries are legally binding for the payouts of annuities, but only the particular calculation of longevity based on the actual annuity portfolio of each life insurer. This judicial condition explains why life-insurers make intense public relation work with regard to a possible underestimation of life-expectancy by the “average” policyholders (Gesamtverband der Versicherer 2023).

Right now German policyholders cannot do much more than having “thrust” in the ongoing work of the supervisory authorities and their control of the actuarial calculations of longevity by each life-insurer separately (including the legal obligation to transfer any possible gains due to an over-calculation of biometric risks—be it death or longevity—back to the policyholders).

Admitted that a pure real return observation might not be sufficient for the total evaluation of the “suitability” especially of a pension product due to the longevity aspect, it should have become evident that German life insurers have a lot of legal discretion for “adjusting” the returns and benefits of their products by using factors like administration and distribution costs, reduced guarantees, longevity, etc. The situation becomes even more complex when taking into account the “turn-around” of key interest rates (Zinswende) in the Eurozone since 2021/22.

12.5 Conclusions

Like policyholders and insurers in other EU member states, German policyholders and insurers were also confronted with a phenomenon from mid-2022 onwards that they hadn’t experienced for 14 years: within a little more than one year key interest rates set by the European Central Bank rose from 0.0% in July 2022 to 4.5% in September 2023 (but back to 2,0% in June 2025). From March 2016 to July 2022, this key interest rate was fixed at 0,0% (“low for long” period), and only in July 2008, the rate had reached 4,25% before, after which a gradual but constant decline began. The crucial question is whether this short-term increase in the key interest rate in 2022/23 will lead to a revival of the classical life insurance with strong guarantees or not. Still it is too early for any definitive answer, nevertheless some assessments can be made.

- Life-insurers: most of them are increasing their bonuses but have not yet raised the “guaranteed interest rate” (only possible with authorization of BaFin). Given the ongoing high volatility in stock and real estate markets on the one hand and the Solvency II rules on the other, it does not seem very likely that they will make a significant shift in their distribution practices. So, as product providers, they will surely continue to focus on products with hybrid or reduced guarantees.

- Policyholders: The transition for German policyholders from full guarantees to hybrid or reduced guarantees represented a profound “learning process” that reshaped long-held attitudes. As a result, it’s less likely that they will undergo another major change, especially considering that the younger generation, on average, is more inclined to act as retail investors using digital tools

- NCA, BaFin: it appears to be too early to make any announcements regarding a possible “turn-around” of the “guaranteed interest rate” authorised for life-insurers, because former “hidden reserves” have now turned into “hidden losses”. However, there is at least some relief in the form of refunds from the obligatory “additional capital reserve” (Zinszusatzreserve) introduced in 2011 to secure the long-term payment obligations of the life insurers which started in 2023. Additionally, BaFin is closely monitoring whether the total number of early cancellations is rising due to the competition from new saving offers by banks, but as of now, this does not seem to be the case on a significant scale (with the exception of one-off contribution products).

As a result, as of 2024/25, the only assessments that can be made are that the “turn-around” of the key interest rates (Zinswende) has not (yet) led to a noticable resurgence of classical life insurance contracts with full “minimum guarantees”. The short period of financial repression seems have come to an end.

Life insurers (like banks) are not increasing the interest rates for their savings products in the line with the rise in key interest rates (and even if they did, this would not be enough to stop the long-term loss of purchasing power). So long-term “real” protection against inflation does not seem to be in place—a bitter truth just for German consumers.

Taking into consideration the inevitable conflict between long-term loss of purchasing power primarily associated with insurance-based pension products like annuities on one hand, and the desire and necessity for coverage of the biometric risk of longevity by many consumers on the other hand, there appears to be only one reasonable compromise: depending on the risk awareness or “risk appetite” policyholders should allocate only a proportionate part of their total retirement savings into an annuity (either deferred or immediate) and invest the larger part in various other financial products such as bank saving plans, investment funds, shares, bonds, etc. By doing so, the best solution should consist of a diversified portfolio of financial products designed to strike a balance between “free” asset allocation and long-term retirement provision that aligns with the individual’s risk tolerance. A long-standing principle of consumer protection in Germany related to retirement provision has always been the clear separation of the “saving process” (by capital accumulation) and of the “risk coverage” (by insurance).

This kind of solution requires “best advice”, which can only be developed and implemented for each individual case by genuinely “independent” financial advisors. The enforcement of “independent advice” for both retail investors and policyholders is part of the proposal outlined in the EU Commission’s Retail Investment Package of (European Commission 2023). From the perspective of German consumers, this initiative should be strongly supported.

In particular, “independent” advice needs full pre-contractual and ongoing information on costs, performance scenarios, and real returns. In the occupational pensions’ sector this can only partly be achieved, since, for example, distribution costs of “direction insurances” and “competitive” IORPs are only disclosed at the product level, with no average figures available. The NCA should take the necessary steps to provide this data separately. Nevertheless, it is obvious that the final real return of any “implementation type” of occupational pension largely depends on the actual contributions from the sponsor company, which can vary widely.

With regard to third pillar private pensions—state subsidised or not—publicly available data indicates that two major factors influence the final real return of these products: costs, especially distribution costs, during the accumulation phase, and biometric costs of longevity during the decumulation phase.

Given the current situation, where no additional legal amendments are expected at least until the forthcoming implementation of the EU Retail Investor Package of May 2023, German consumers have little choice but to rely on the NCA, BaFin. BaFin has announced its intention to strengthen its supervision of the conduct of business by life-insurers. In May 2023, Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (2023) published an “Information Sheet” (Merkblatt) aimed at enhancing the supervision of the “appropriate benefit for clients”, which must be secured mainly by enforcing the product approval process already stipulated by the Insurance Distribution Directive (IDD). Particularly relevant are the precise determination of target markets, realistic performance scenarios, disclosure of returns in nominal and real figures (the latter after accounting for costs and inflation), prohibition of possible conflicts of interest due to inducements, and BaFin’s focus on distributors with particularly high commissions.

In fact, it can be said that nearly all the relevant factors that could have a significantly detrimental impact on the real return of private life and annuity insurances (“value for money”) are included in this supervisory approach. Additionally, we emphasize the importance of controlling annuity factors and their correlation with the assumed life expectancy, which should not deviate significantly from general statistics. Consequently, it is up to the BaFin itself to prove to the German consumers that it will effectively implement its own supervisory objectives and should not be considered as a “toothless tiger” in the long run. 14 An exciting story that will be followed as closely as possible.

Acronyms

- AuM

- assets under management

- BaFin

- Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht

- DAV

- Deutsche Aktuarsvereinigung

- DC

- Defined contributions

- ECB

- European Central Bank

- EET

- Exempt Exempt Taxed

- ETF

- exchange-traded fund

- EU

- European Union

- GDV

- Gesamtverband der Versicherer

- GRV

- Gesetzliche Rentenversicherung

- GWP

- gross written premium

- IBIP

- insurance-based investment product

- IDD

- Insurance Distribution Directive

- IORP

- institution for occupational retirement provision

- KID

- Key Information Document

- NCA

- national competent authority

- PF

- Pensionsfonds

- PIB

- Produktinformationsblatt

- PK

- Pensionskasse

- TEE

- Taxed Exempt Exempt

- p.p.

- percentage point

Total bonus of life insurances in Germany in 2024 - private annuities: 2.46%; capital life: 2.61% (Statista 2025)↩︎

In April 2024 for the first time the Federal Ministry of Finance published statistics on the pay-outs of Riester Pensions. In 2022 the average of the monthly pay-outs amounted to EUR 132. The ministry stressed that this low figure is mainly due to short contribution periods up to now and in the long run pay-outs will increase. Consumer protectors criticized these figures by stressing the low “return on investment” and over-calculated life-expectancies by life-insurers Krieger (2024)↩︎

Not surprisingly this legislative proposal provoked huge public discussions on its credibility (see, for instance “Stellungnahme der DAV und des IVS zum Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Stabilisierung des Rentenniveaus und zum Aufbau eines Generationenkapitals für die gesetzliche Rentenversicherung (Rentenniveaustabilisierungs- und Generationenkapitalgesetz)” 2024)↩︎

A comprehensive overlook over the legislative acts for the reform of Pillars I, II and III in 2024 and the opposite of positions of insurers, investment companies and consumer representatives can be found in Horvath (2025).↩︎

Cf. Website of the national Digital Pension Tracking System, Deutsche Rentenversicherung Zentrale Stelle für die Digitale Rentenübersicht (2024)↩︎

For more details on the specific legislation on investments (Kapitalanlagen) and technical reserves (Sicherungsvermögen), see Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (n.d.).↩︎

Just one example: surprisingly in October 2020 Allianz announced that its “Pensionskasse” will go into run-off and will offer only “Direct Insurances” from 2022 on. It was the second biggest PK in Germany with more than 838 000 future beneficiaries and more than 27 500 current beneficiaries (balance sheet: EUR 12.8 billion) in 2018. The main raison for this decision was the ongoing low interest rate phase and the problem of guarantees given. If one of the biggest players in the national market takes such a step, it was interpreted as a sign that other smaller IORPs could follow (see comment in Bazzazi 2020).↩︎

For more details on the different options to offer occupational pensions (Versorgungszusagen) with and without certain minimum payouts or guarantees (similar to life-insurers) and the importance of the sponsors, see Arbeitsgemeinschaft für betriebliche Altersversorgung (n.d.).↩︎

For more details on the “Law strengthening occupational pensions”, cf. Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (2012) and Arbeitsgemeinschaft für betriebliche Altersversorgung (2017).↩︎

One of the first criticisms was published by German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) in 2012, see Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (2012).↩︎

For more details on these basic differences, go to the Information Sheet of the German Association of Insured (BdV) (Versicherten e. V. n.d.).↩︎

BaFin regularly publishes figures on distribution and administration costs of Pensionskassen as well in total for all PK as for particular PK via special Excel tables (tables 240 and 260 included in the “Statistics on Insurers – section: Pensionskassen”), but these tables can only be found and interpreted by very experienced policyholders with a highly advanced level of financial education, https://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Statistik/Erstversicherer/dl_st_22_erstvu_pk_va.html.↩︎

For more details on biometric risk coverage, cf. BaFin website on life-insurances.↩︎

In August 2024, in July and in August 2025 BaFin published the results of supervisory activities linked to pension products, unit-linked and hybrid products, and so-called “net of costs” life-insurances (“Netto-Policen”). BaFin stressed that mainly transparency related to costs, granularity of target markets, portfolio shiftings and performance scenarios were not sufficient in many cases. But as no “naming and shaming” was published, the effective practical value of these conclusions was quite restricted for consumers.↩︎