Product categories

|

Reporting periods

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Pillar | Earliest data | Latest data |

| Pillar II pension funds | Occupational (II) | 2003 | 2024 |

| Pillar III pension funds | Voluntary (III) | 2003 | 2024 |

Kokkuvõte

Eesti pensionisüsteem on tüüpiline Maailmapanga mitme sambaga süsteem, mis põhineb isiklikel pensionikontodel. Aastat 2024 iseloomustasid erakordsed tootlused mõlema pensionisamba vahendite puhul. Isegi kui võtta arvesse endiselt kõrget (kuid langevat) inflatsiooni, olid reaaltootlused peaaegu kõikide pensionifondide puhul positiivsed. Teise samba fondide kaalutud keskmine tootlus oli 16,93%, võrreldes kolmanda samba positiivse tootlusega 20,51% (mõlemad nominaalsed tootlused). Endiselt kõrge inflatsiooni tõttu oli teise samba fondide inflatsiooniga korrigeeritud reaalne tootlus 12,36%. Kolmanda samba reaalne tootlus oli 15,80%. Aasta 2024 oli üldiselt positiivne ja tootlus aitas pensionisäästudel taastuda 2022. aasta kahjumist nii nominaalselt kui ka reaalselt. Teise samba fondide pikaajaline kaalutud keskmine reaalne tootlus ajavahemikul 2003–2024 oli 0,3% aastas. Kolmanda samba fondide puhul oli sama perioodi näitaja 1,6% aastas. 2020. aastal jõustunud vastuoluline pensionireform muutis varem kohustuslikud II samba pensionifondid vabatahtlikuks ja võimaldas pensionisäästjatel enne pensionile jäämist oma II samba säästud likvideerida. Paljud säästjad on siiski kasutanud võimalust suurendada pensionimakseid üle kohustusliku 2% piiri, et kompenseerida riikliku PAYG-süsteemi eeldatavat madalat asendusmäära pensionile jäämisel.

Summary

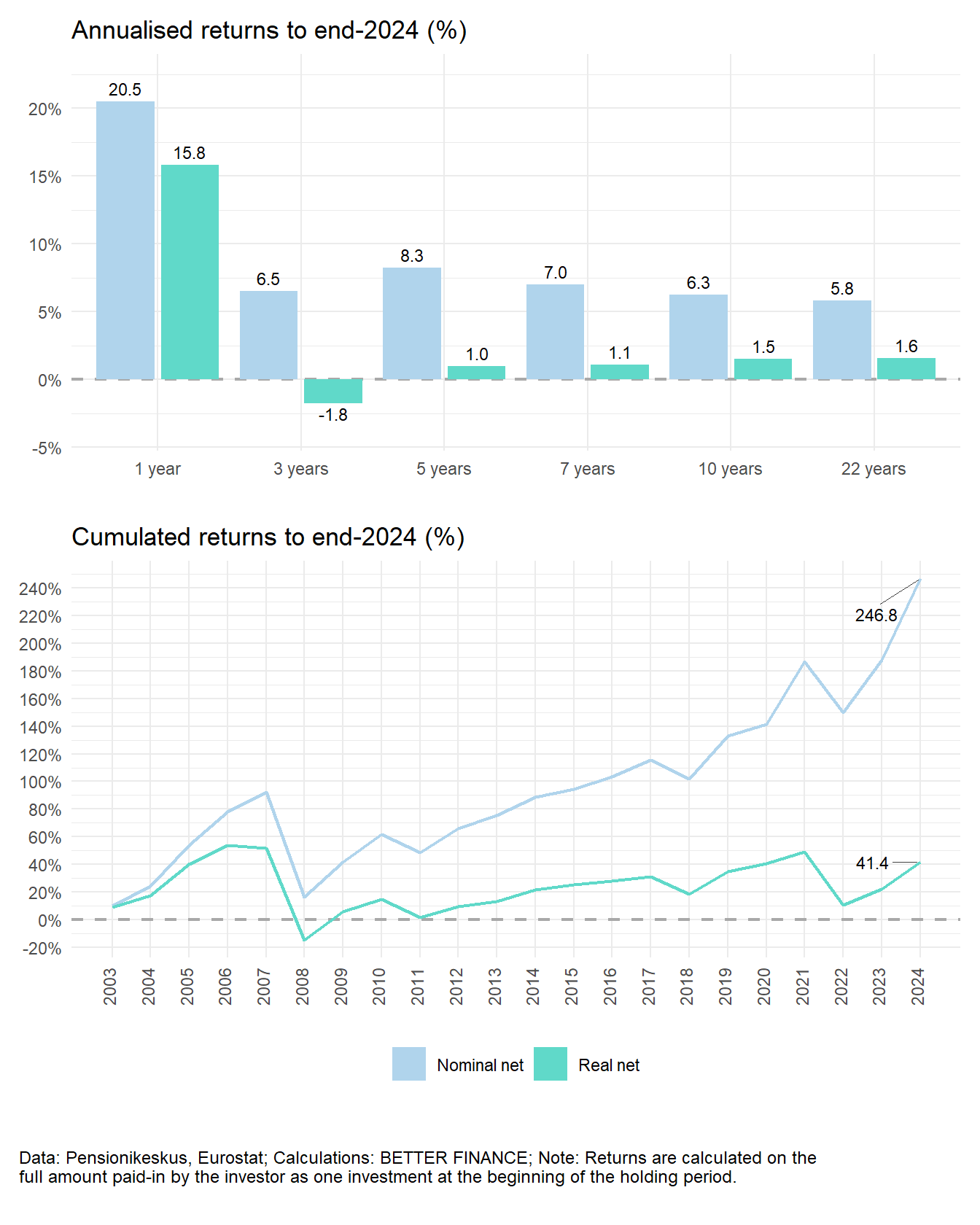

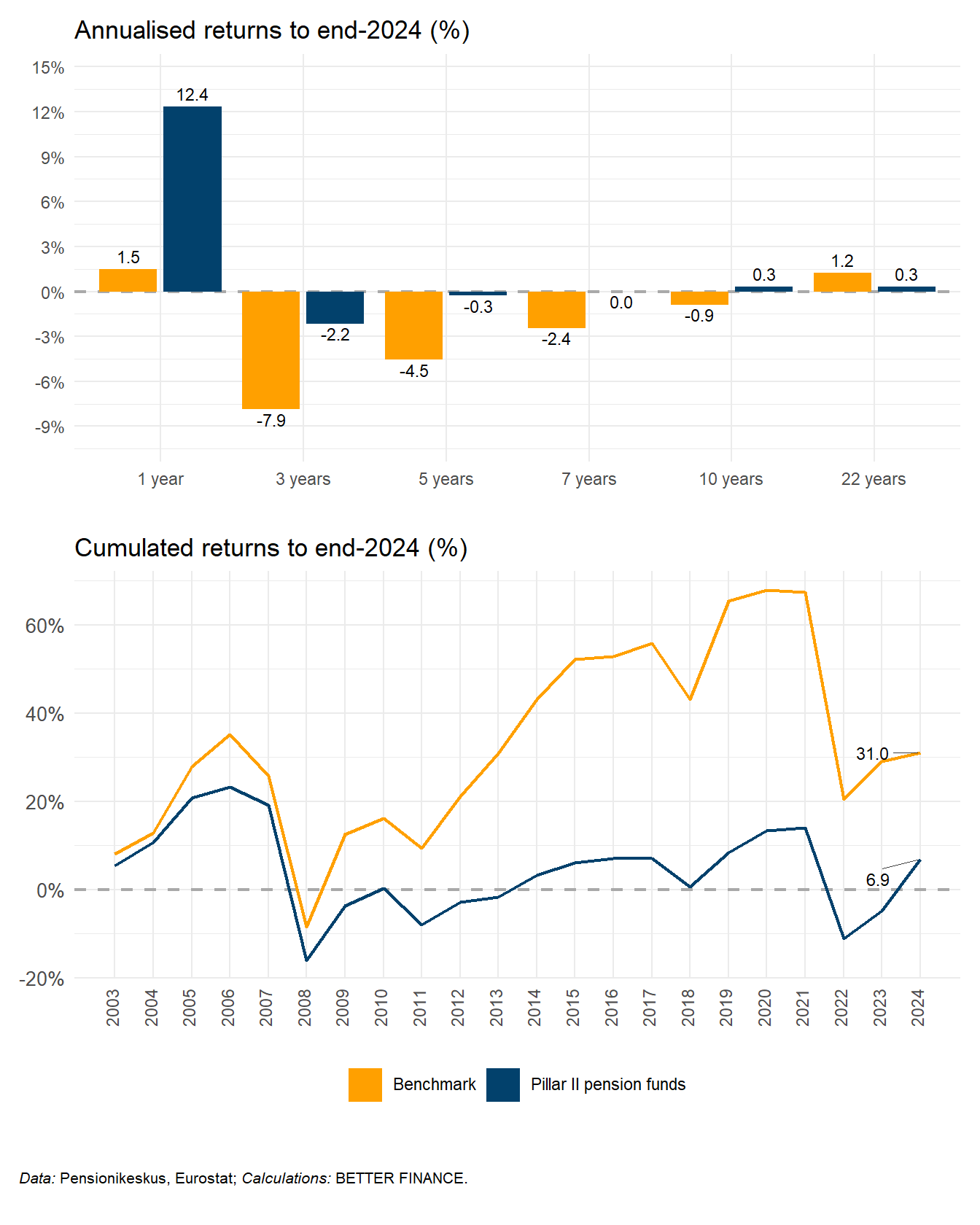

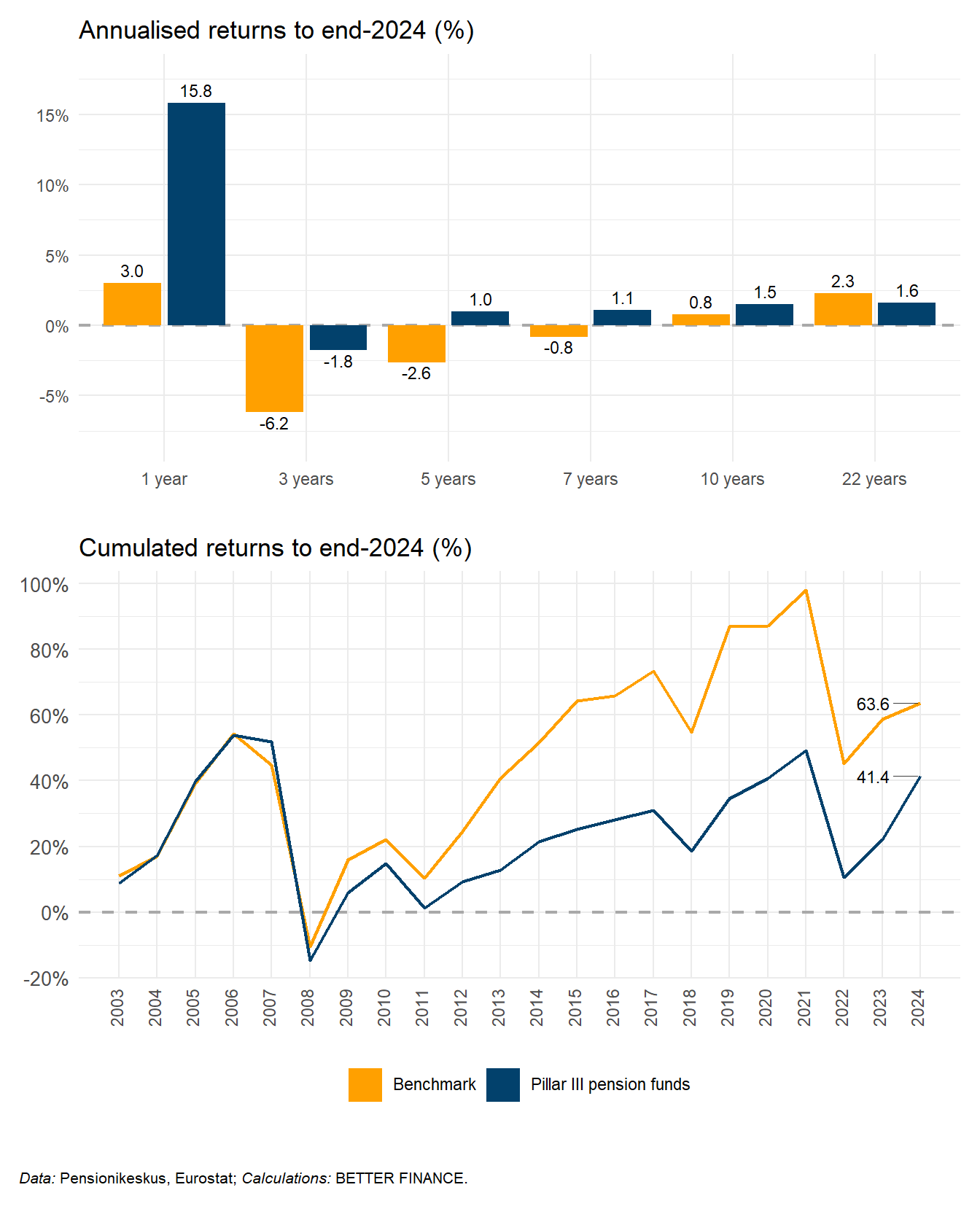

The Estonian pension system is a typical World Bank multi-pillar system based on personal pension accounts. The year 2024 was characterised by exceptional returns for both pension pillar vehicles. Even if the still higher (but falling) inflation was taken into account, the real returns were positive for almost all pension funds. The weighted average return of second pillar funds was 16.93% compared to a positive return of 20.51% in the third pillar, both in nominal returns. Due to the still elevated inflation, the inflation-adjusted real return on second pillar funds was 12.36%. The third pillar’s real return was 15.80%. Year 2024 was overall positive and the returns helped pension savings to recover from the 2022 losses both in nominal as well as in real terms. The long-term weighted average real return for second pillar funds over the period 2003-2024 was 0.3% per annum. For third pillar funds, the figure was 1.6% per annum over the same period. The controversial pension reform, which came into force in 2020, made the formerly mandatory Pillar II pension funds voluntary and allowed pension savers to liquidate their Pillar II savings before retirement. However, many savers have adopted possibility to increase pension contributions above mandatory 2% in order to tackle expected low replacement rate at retirement from the state PAYG scheme.

9.1 Introduction: The Estonian pension system

This country case aims to present an overview of the Estonian pension system, with a particular emphasis on savings-based pensions products, especially pension funds that are part of the auto-enrolled (formerly mandatory) Pillar II pension funds and the voluntary Pillar III pension funds.

The year 2024 brought quite exceptional positive returns for Estonian pension savings. Pillar II pension funds returned almost 17% nominal returns on average (12.36% when adjusted for purchasing power), while savings invested in Pillar III funds increased by almost 21% on average (almost 16% when adjusted for inflation).

Holding period

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | 7 years | 10 years | Whole reporting period | to... | |

| Pillar II pension funds | 12.4% | -2.2% | -0.3% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.3% | end 2024 |

| Pillar III pension funds | 15.8% | -1.8% | 1.0% | 1.1% | 1.5% | 1.6% | end 2024 |

| Data: Pensionikeskus, Supplementary pension funds reports, Eurostat; Calculations: BETTER FINANCE | |||||||

As can be seen in Table 9.1 the positive real returns in 2024 have been able to deliver the positive long-term real returns. While 0.3% does not sound like a lot, then it is important to consider that pension savings are a very long-term investment. The period before first starting to work (and auto-enrolling in the Pillar II pension) and the first pension payment may be as long as 45 years.1

Since the introduction of the current pension system in the early 2000s, successive governments have made various changes to the laws governing the pension system in general and Pillar II pension funds in particular. Many of these changes have been to add additional flexibility and fix issues in the early conservative design in the system with the aim of helping achieve better returns in the long run. However, the most recent reform which took place in 2021, proved also to be the most controversial.

The previously mandatory Pillar II, in effect, was changed into a voluntary pension fund with auto-enrolment. Pension savers who had been enrolled in the Pillar II could now take out any accumulated savings at any age and opt out of the Pillar II entirely. About 30% of people with an Pillar II pension savings account had liquidated their assets between 2021 and end of August 2023. The amounts withdrawn equal approximately 4% of Estonia’s gross domestic product (GDP).2

Pension system in Estonia: An overview {sec-ee-intro-overview}

The Estonian old-age pension system is based on the World Bank multi-pillar approach. This is the result of a fundamental pension reform which began in 1998 and became fully operational by 2003. Accordingly, this report analyses the returns from the first full year of operation (2003) until the last full year of data availability (2024).

| Pillar I | Pillar II | Pillar III |

|---|---|---|

| State Pension | Funded pension | Supplementary pension |

| Mandatory | Formerly mandatory, voluntary with auto-enrollment from 2021 | Voluntary |

| PAYG | Funded | |

| Defined benefit | Defined contribution – Individual pension accounts | |

| Publicly managed by Social Insurance Board (government entity) | Self-managed or investment fund | Investment fund or insurance contract |

| Retirement is possible up to 5 years earlier than statutory retirement age if minimum service requirements are fulfilled. Early retirement reduces future payments; delaying retirement increases them. | Funded by a formerly mandatory contribution (2% of salary) and Social Security deduction (4%). Since 2023, individuals may contribute 4% or 6%. Since 2021, early withdrawal is possible at fixed dates, regardless of age.a | The supplementary Pillar III has always been flexible and voluntary. Contributions are up to tax-deductible limitsb. Savings can be withdrawn at any time, but non-retirement payouts are generally taxed. |

| Quick facts | ||

| Number of old-age pensioners: 0.3102 mln. (active population: 0.697 mln.) | Administrators: 5 | Administrators: 5 investment fund providers and 5 providers of unit-linked pension insurancec |

| Average old-age pension: EUR 698.68d | Funds: 26 | Funds: 17 |

| Average salary (gross): EUR 1981d | AuM: EUR 5967 mln. | AuM: EUR 890 mln. |

| Average replacement ratio (Pillar I): 35.27% gross (38% including all pillars) | Participants: 0.501 mln. | Participants: 0.198 mln. |

|

a Subject to 20% income tax if >5 years before retirement, 10% if within 5 years of retirement. b Full income tax deduction up to 15% of annual gross income or EUR 6000, whichever lower. c Two entities, SEB and Swedbank, offer both III pillar investment funds and insurance contracts. d Data: Statistikaamet. |

||

The state pension (Pillar I) should guarantee the minimum income necessary for subsistence after retirement. It is based on the pay-as-you-go (PAYG) principle of redistribution, i.e. the social taxes paid by today’s employees cover the pensions of today’s pensioners.

For those, who qualify for the old-age pension by reaching the pensionable age and minimum of 15 years of service, the old-age pension consisting of various components individual to each pensioner, related to the years of pensionable service and the social security deductions during that pensionable service, which in turn depend on the salary of the person (Sotsiaalkindlustusamet, n.d.).

The old-age pension consists of four parts:

- The main or basic part;

- The pensionable service period component, which is calculated for employment until December 31st, 1998;

- The insurance component– the personally calculated additional payment;

- The joint part consists of:

- an insurance component of 50%. The size of the insurance component is calculated based on the received social tax. It is calculated in the same manner as the currently accumulated insurance component. For example, the size of the insurance component of a person earning average wages in Estonia is 1.0.

- a solidary component of 50%. The solidary component is 1.0, if the social tax has been paid for the person on at least 12 times the minimum wages during the year. If the social tax paid for the person is less than the minimum annual wages, the solidary component shall be calculated proportionally.

The amount of the pensionable service period component depends on the length of employment, or the working years of the pensioner. Additional pension is calculated for the years deemed equal to employment, e.g. raising of children, compulsory military, studies at a university or vocational education institution, but also for the time the employee was temporarily incapable for work. The specific list is available in the State Pension Insurance Act. There are also pension supplements for parents for each child raised.

The average I pillar old-age pension in Estonia was EUR 698.68 in 2024, which guaranteed a replacement ratio of 35% compared to the average gross salary (Statistikaamet, n.d.). Due to the progressive nature of the tax-free allowances, the replacement ratio would be 49.4% in net terms, assuming no additional annual income or deductions apply to the average pension and salary respectively. 3 A person needs to have had at least 15 years of pensionable service to qualify for a old-age pension. However, those who have reached retirement age, but do not qualify for old-age pension are eligible for a minimum “national pension”, provided they had legally resided in Estonia at least 5 years before applying and do not receive a pension from any other jurisdiction (Sotsiaalkindlustusamet, n.d.). As of April 2024, this minimum national pension is EUR 372.05 per month and EUR 393.26 per month as of April 2025. This amount is also indexed annually along with old-age pensions (Sotsiaalkindlustusamet, n.d.).

The statutory retirement age in Estonia was 64 years and 6 months in 2024 (for those born in 1958) and is set to rise to 65 years by 2026. From 2027 onward, the retirement age will be increased in line with increases in life expectancy, but not more than 3 months of increase in any calendar year (Sotsiaalkindlustusamet, n.d.).

9.2 Long-term and pension savings vehicles in Estonia

Second pillar: Formerly mandatory pension funds and personal Pension Investment Accounts

As can be seen from Figure 9.1, the vast majority of Estonian pension savings are collected in Pillar II pension funds.

The funded Pillar II pension is based on the accumulation of assets (savings) – a working person saves for their pension, paying 2% of the gross salary to the selected pension fund. In addition to the 2% that is paid by the individual, the state adds 4% out of the current social tax that is paid by the employee and retains 29% (out of 33%). The salary linked “insurance element” of the I pillar state pension of a person who has subscribed to the funded pension is also lower respectively (for the years in which one receives 16% for the state pension instead of 20%).

Subscription to the funded pension was compulsory for those born in 1983 or later, but it has become voluntary starting January 1st, 2021. The funded pension has always been voluntary for those born between 1942 and 1983. For these people, subscription was possible in seven years; from May 1st, 2001, until October 31st, 2010. From January 1st, 2021, all persons born in 1970 or later, who are not already subscribed to the Pillar II pensions, will be able to apply to subscribe to pillar II pensions. Persons who have previously unsubscribed may re-apply after at least ten years from the date when they were unsubscribed.

From 2021, it became possible to opt-out of the second pillar pension and to liquidate any previous savings held under it. This has led to a large number of savers taking out their accrued savings before their statutory retirement age and significantly decreasing the coverage of the second pillar. At the time of writing of this report, about 491 000 people had assets in their second pillar pension account, while over 210 000 people had taken out their savings, totalling close to EUR 1.5 billion.

This was the reason for the significant reduction in assets under management (AuM) of Pillar II pension funds in 2021 and 2022, which can be seen in Figure 9.1. The withdrawals were largest in 2021. However, the impact was somewhat mitigated by high nominal returns on investment that year. In 2022, while the amounts being withdrawn early from the system decreased, the AuM still declined significantly from the combination of both early withdrawals and negative nominal performance of investments.

From 2021 onwards, it became possible for savers to manage their Pillar II pension assets themselves through personal Pension Investment Accounts. However, the penetration of this new form of pension savings remained insignificant in 2024, with only approx. 1% of Pillar II participants actively use this option in 2022–2024 (Pensionikeskuse Statisika, n.d.).

Third pillar: Supplementary Pension Funds and Pension Insurance accounts

The supplementary funded pensions scheme, or Pillar III, is a part of the Estonian pension system and is governed by the same act that governs Pillar II, the Funded Pension Act.

This scheme has been introduced with the aim of helping to maintain the same standard of living and adding more flexibility in securing a higher and/or stable stream of income after one reaches the age of 55. Therefore, the supplementary pension has been designed to help achieve a recommended level of 65% gross replacement ratio of an individual’s previous income in order to maintain the established standard of living.

Supplementary pension participation is voluntary for all persons who can decide to save either by contributing to a voluntary pension fund or by entering a respective supplementary pension insurance contract with a life insurance company. The amount of the contributions is determined solely by the free choice of an individual and can be changed during the duration of the accumulation phase. There is also a possibility to discontinue contributions (as well as to finish the contract).

The supplementary funded pension contracts can be made with life insurers as pension insurance or by acquiring pension fund units from fund managers. As there is unfortunately very little transparency regarding the charges and return of Pillar III pension insurance contracts, this report focuses only on supplementary pension funds as third pillar savings products.

9.3 Charges

Charges of Pillar II funds

Starting from the data year 2017, Estonian Pillar II investment funds are obliged to report the total expense ratio (TER) for a given year. This ratio is designed to present investors with a transparent and easily comparable summary of the annual costs and fees deducted from their pension savings, expressed as a percentage of invested assets.

The TER includes:

- the fee paid to the fund manager for the management of the fund or the fees, charges and expenses directly related to the management of a public limited fund (management fee);

- the fee paid to the depositary for the services provided (depositary’s charge);

- the transfer fees and service charges directly related to transactions performed for the account of the fund and other fees, charges and expenses related to the management of the fund and specified in the basic documents of the fund;

- success fees.

In addition to the above fees, it is also possible for the pension funds to charge unit redemption fees, however these are capped by law at just 0.05% for conservative pension funds and 0.1% for all other Pillar II funds and in practice no redemption fees are usually charged by Pillar II investment funds on the Estonian market.

The option of applying a success fee became possible as of January 1st, 2019 and intended to better align the interests of the investors and asset managers. The success fee for a given year is limited by law to a maximum of 20% of the excess of the increase in net asset values over the reference index and to 2% of the asset value of this pension fund, whichever limit is lower. Conservative pension funds do not have the right to apply a success fee.

As of September 2nd, 2019, the management fees of Pillar II pension funds were legally capped at 1.2% for conservative pension funds and 2% for all other Pillar II funds. These funds are also legally required to reduced their management fees in line with the growth of assets of the fund. Namely, after a Pillar II pension fund reaches EUR 100 million of AuM , the fund manager is obliged by law to reduce the base management fee for each additional EUR 100 million of AuM by at least 15 per cent compared to the rate of the base management fee applicable to the previous EUR 100 million. Funds are no longer required to enforce this reduction when the yearly base management fee reaches 0.4% of AuM .

The idea of the obligatory reduction of management fees was to bring down the overall level of fees and charges when economies of scale are achieved, while allowing for higher initial fees to ensure sufficient competition between fund providers and more choice for consumers in Estonia’s relatively small pension market.

As can be seen from Table 9.4, this decrease in charges was initially slow to materialise. This was likely due to a combination of factors:

- The fragmentation of the small market between relatively many investment funds — average fees even increased at times, due to the entrance of new funds with higher fees into the market;

- Relatively slow initial asset accumulations — since the Pillar II was mandatory only to people who were at the beginning of their working life. As we saw in figure 1 in the previous section, only in 2014, more than a decade after the launch of the system, did total AuM reach EUR 2 billion, whereas already by the end of 2018 the EUR 4 billion limit was in sight.

However, between 2013 and 2020 a very significant decline in average management fees can be observed, with management fees falling from 1.5% to just 0.6%. Again, there were likely several contributing factors, including:

- Accelerating increases in AuM during those years;

- Consolidation in the market, with Danske Bank’s Pillar II funds sold to LHV in 2016.

The entrance into the market of low-cost index funds from 2016 onwards, first by LHV and Tuleva (a new entrant offering only passively managed mutual funds), but eventually followed by all Pillar II market participants

| Year | Admin. and mgt. fees | Total Expense Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 1.53% | NA |

| 2004 | 1.54% | NA |

| 2005 | 1.55% | NA |

| 2006 | 1.55% | NA |

| 2007 | 1.55% | NA |

| 2008 | 1.56% | NA |

| 2009 | 1.56% | NA |

| 2010 | 1.48% | NA |

| 2011 | 1.49% | NA |

| 2012 | 1.47% | NA |

| 2013 | 1.46% | NA |

| 2014 | 1.45% | NA |

| 2015 | 1.25% | NA |

| 2016 | 1.22% | NA |

| 2017 | 1.08% | 1.19% |

| 2018 | 1.01% | 1.18% |

| 2019 | 0.70% | 0.86% |

| 2020 | 0.60% | 0.87% |

| 2021 | 0.58% | 0.97% |

| 2022 | 0.57% | 1.06% |

| 2023 | 0.54% | 0.77% |

| 2024 | NA | 0.73% |

| Data: Pensionikeskus Calculations: BETTER FINANCE. | ||

While data regarding the TER is available only starting from 2017, it’s likely this followed a similar trend overall. However, in 2023-2024 the TER of funds decreased slightly compared to 2021-2022, likely at least in part due to success fees associated with high market returns in the 2020-2021 period. Here it’s important to note that success fees, which are inherently backward-looking, are charged based on the previous year’s results and figure in the TER of the year following the one where the “success” was achieved.

Other than success fees, the remaining difference between the TER and the management fees can mostly be explained by many pension funds themselves investing into other funds. The management fees of such underlying funds are included in the TER, but not in the management fee of the fund itself.

Charges of Pillar III supplementary pension funds

The structure of charges that can be applied to Pillar III pension funds is similar to Pillar II funds, with the biggest difference being that caps on the various types of fees and charges (such as management fees or redemption fees) are higher in many instances. This combined with much smaller assets under management and the associated lack of economies of scale meant that the average fees were often higher in the third pillar compared to the second pillar.

However, in the last years, the proliferation of new index funds in the supplementary pension fund market — from 2021 onward every fund provider offered at least one index fund — and the relative success of these funds in attracting savings has led to the TER of Pillar III funds dropping slightly lower than Pillar II funds on average.

Unfortunately, due to changes in the way data on the charges of supplementary pension funds is presented in public databases, it was not possible to retrieve long-term comparable data series on the charges of Pillar III funds, but overall, the dynamic has been fairly similar to that of Pillar II funds.

| Year | Admin. and mgt. fees | Total Expense Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 0.80% | 0.96% |

| 2022 | 0.72% | 0.87% |

| 2023 | 0.65% | 0.76% |

| 2024 | NA | 0.76% |

| Data: Supplementary pension funds reports Calculations: BETTER FINANCE. | ||

9.4 Taxation

Now that both second and third pillar pension funds are effectively voluntary savings products, their tax treatment remains perhaps the biggest attraction of saving under either or both Pillar II and III pension vehicles compared to other potential savings and investment products

| Product categories |

Phase

|

Fiscal Regime | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contributions | Investment returns | Payouts | ||

| Pillar II pension funds | Exempted | Exempted | Taxed | EET |

| Pillar III pension funds | Exempted | Exempted | Taxed | EET |

| Source: BETTER FINANCE own elaboration, based on Pensionikeskus. | ||||

| Note: Taxation of payouts depends on the timing and method of payout | ||||

As can be seen from Table 9.6, contributions to II and III pillar pension funds are exempted from all taxes, although in the case of the III pillar, the annual tax deductibility is limited to a maximum of 15% of the savers’ annual income or to EUR 6000, whichever is lower. The investment returns/capital gains of both II and III pillar pension products are also entirely exempted from tax in the accumulation phase. In the payout phase, the taxation depends on the pillar and specific circumstances. The Pillar I pension is subject to income tax. As of January 1st, 2025, the income tax rate is 22%.. However, basic exemptions (non-taxable amounts) apply to both the working population as well as pensioners.

There has long been a tacit political agreement under successive governments, regardless of their composition, that the amount of annual income tax exemption applying to pensioners be at least as high as the average state (Pillar I) old-age pension.

For the Pillar II and Pillar III savings-based pension, the taxation regime depends on when and how the payout of savings is settled. For both Pillars, when a saver has less than 5 years left until pensionable age, it’s possible to sign an agreement with a life insurance company for a lifetime annuity pension. Under this option, the pension payments are exempted from taxes (Pensionikeskus n.d.). Alternatively, it’s possible to make a fixed duration agreement, either with an insurance company or directly with the pension fund—what is called a “fund pension”. As long as the fixed duration at the moment of the agreement is as long or longer as the average life expectancy of the person and the payments are monthly or quarterly, the payouts are also exempted from taxation.

For both Pillars II and III, in the case of either a one-time payout or a fixed-term pension contract that is shorter than the “recommended” duration, calculated based on life expectancy, a 10% tax rate applies, as long as the payout starts at less than 5 years before pensionable age. However, if the pension savings are paid out more than 5 years before reaching the pensionable age, the full income tax rate is applied. Units of Pillar II and III pension funds are also inheritable. Payments to successors are taxable with the income tax rate established by law. However, successors may also choose to transfer the inherited pension fund units to their own pension account, which would not be taxable.

9.5 Performance of Estonian long-term and pension savings

Real net returns of Estonian long-term and pension savings

For the pension saver, the most important metric of the performance of a savings or investment product is how it helps to conserve and ideally increase the purchasing power of their savings over the long term to allow a more economically comfortable retirement. For this, the net investment returns of pension savings should exceed inflation.

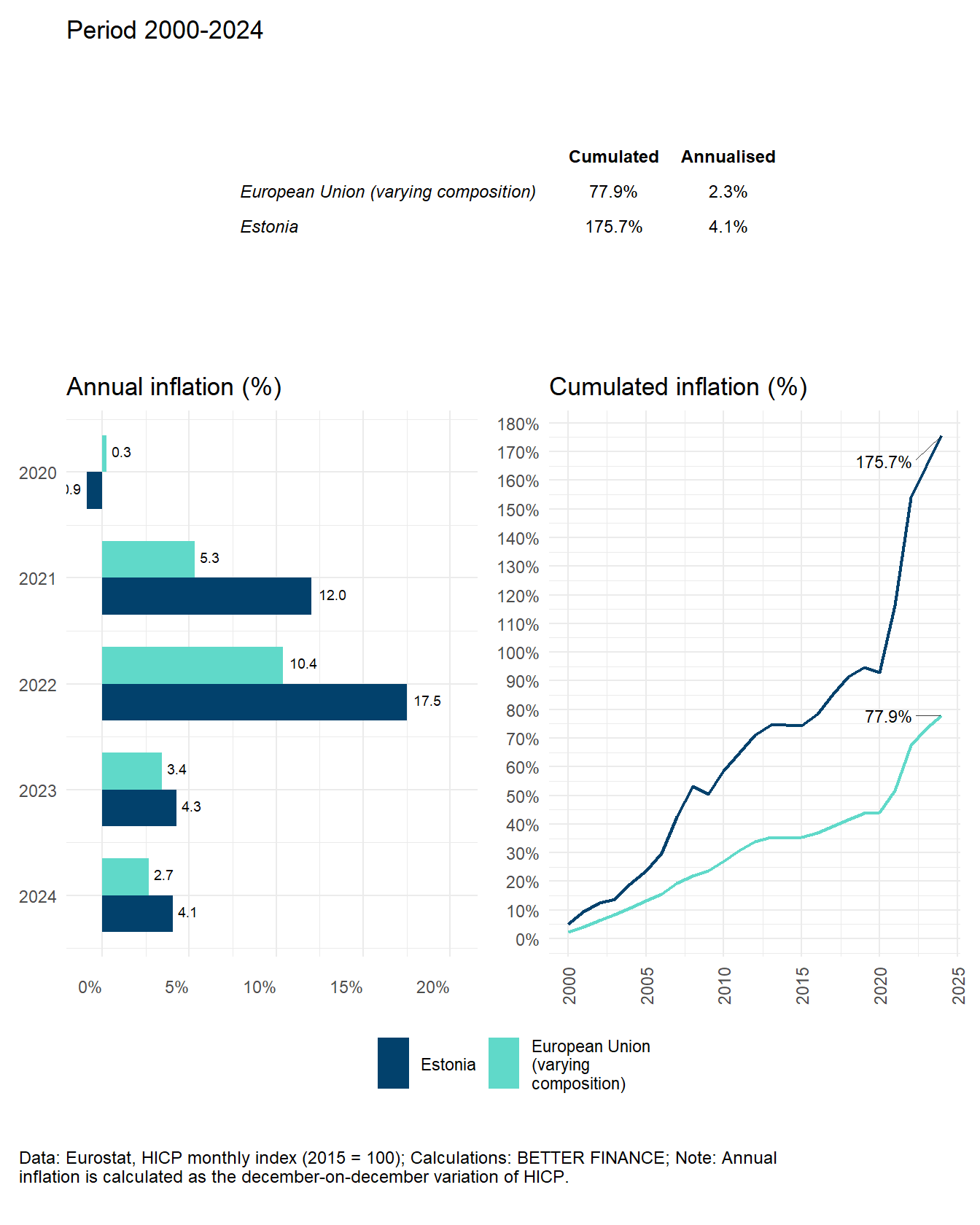

As can be seen from Figure 9.2, inflation surged to very high levels in 2021 and 2022 in the European Union, but especially in Estonia. The main drivers of inflation in 2021–2024 are well-known and much discussed: post-pandemic savings and supply chain issues, the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation and the energy crisis this caused. The fact that inflation reached much higher levels in Estonia than in the European Union (EU) on average can be attributed to both the comparatively small and open economy of Estonia as well as to the relatively closer proximity and stronger economic and social ties to Ukraine and Russia. The extraordinarily high inflation was mirrored in other Eastern European countries.

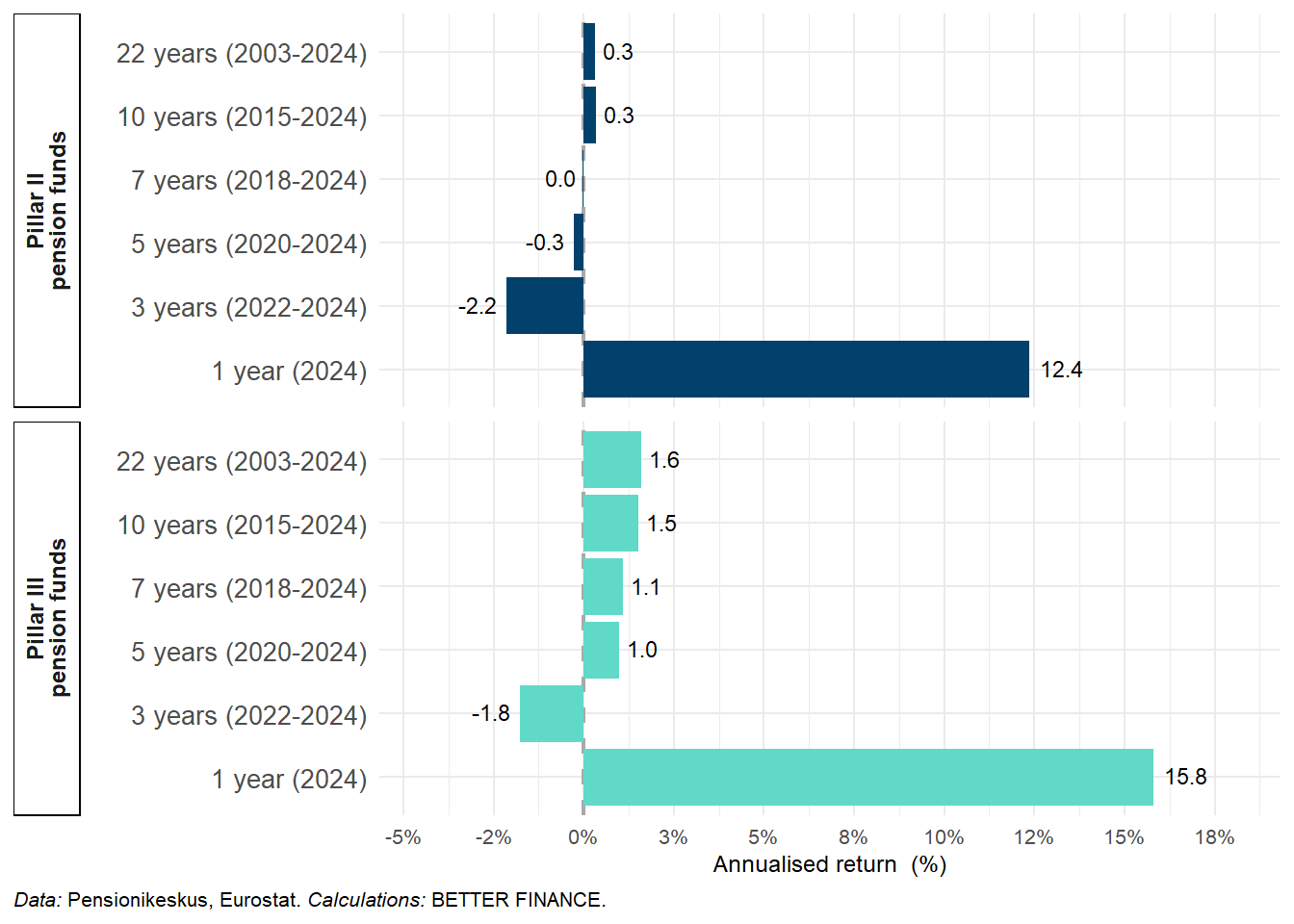

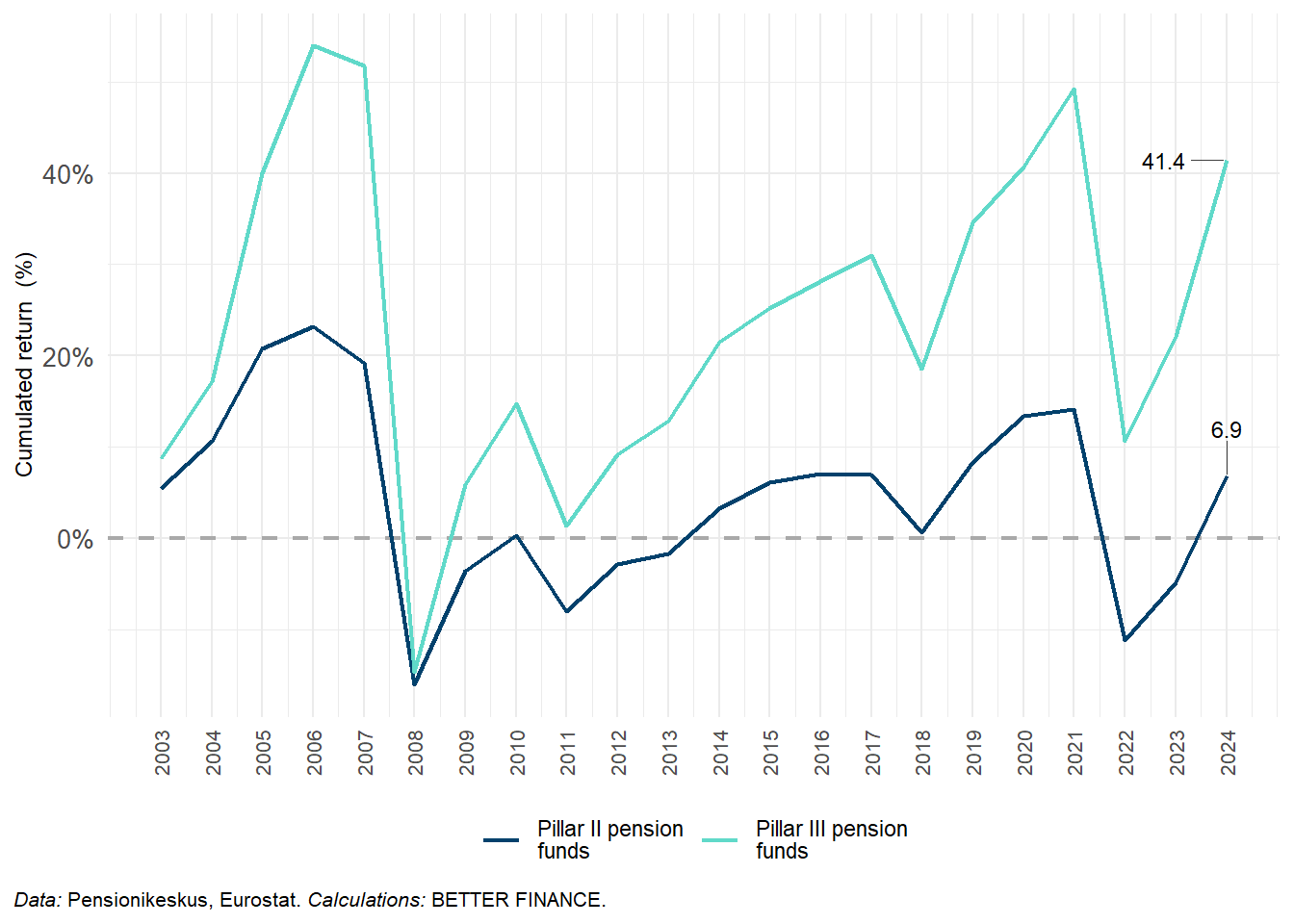

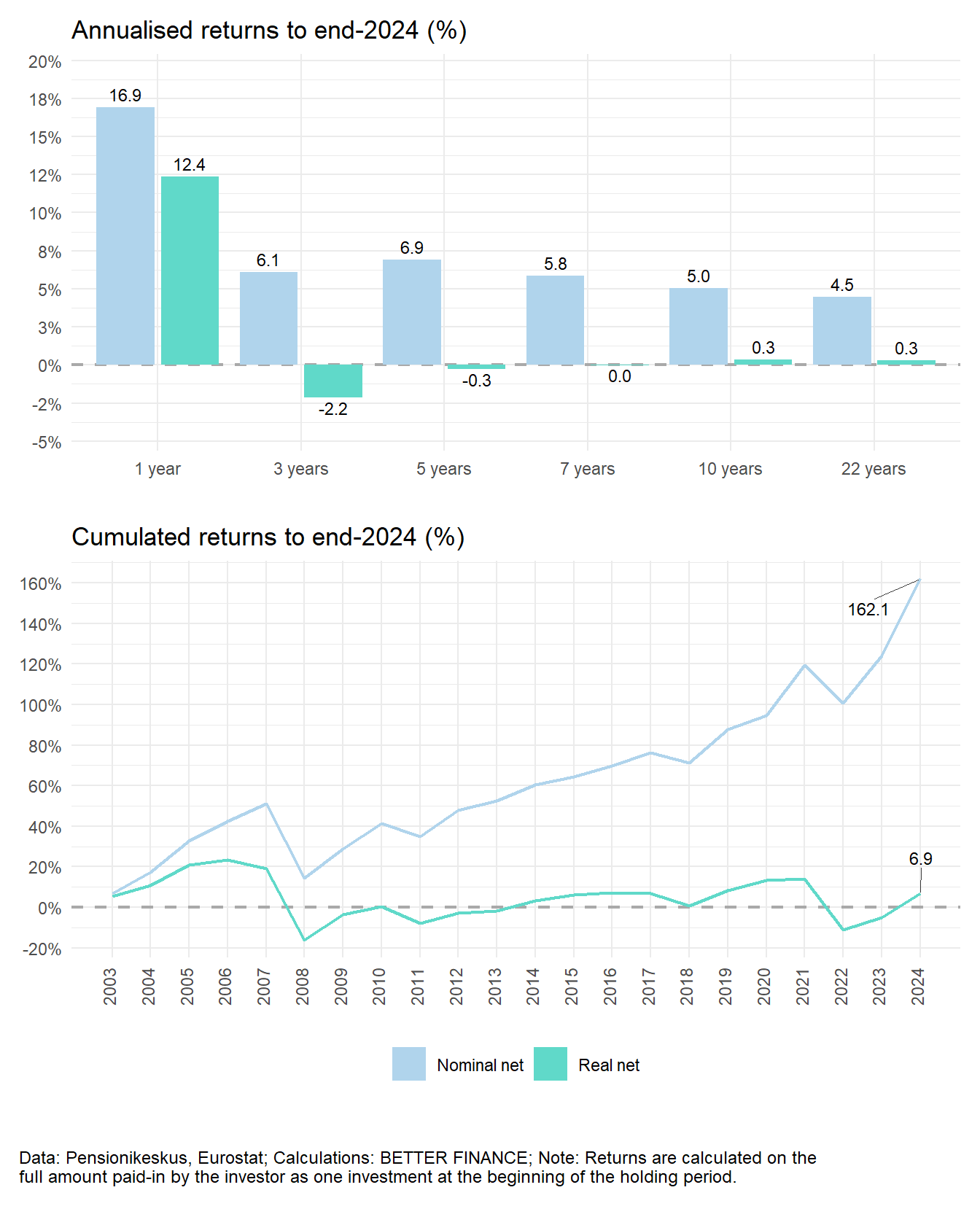

As can be seen from Figure 9.3 and Figure 9.4, positive nominal returns in 2024 helped to offset the impact of high inflation on the purchasing power of pension savings. Overall positive returns in 2024 were able to offset the 2022 “perfect” storm of high inflation and sharply negative nominal returns that led to massive losses in the purchasing power of pension savings, with Pillar II funds declining approximately 22% on an inflation-adjusted basis while losses in the Pillar III exceeded 25%. After 2023 and 2024 positive nominal as well as real returns, both pillars are delivering positive annualised real returns and thus increasing the real value of savings.

Of course, what matters most in pension savings is the long term. As can be seen from the figures in Figure 9.5, the underwhelming past real returns combined with the disastrous results of 2022 led to the average (asset-weighted) annual returns of Pillar II pension savings to be negative across that turns positive in 2024, with a 0.3% positive return over 10 years and 0.3% since the launch of pension investment funds in 2003.

In the case of the supplementary Pillar III pension funds, 10-year returns are still in positive territory of 1.5%, with returns for shorter periods being close to 0 and the long-term return since the introduction of the supplementary pension system being slightly positive at 1.6% on an annualised basis (see Figure 9.6) especially due to the positive return during the period 2023–2024.

Do Estonian savings products beat capital markets?

To put the performance of Estonian Pillar II and III investment funds into context and draw conclusions, it is important to compare the performance with capital-market benchmarks. Table 9.7 shows the chosen benchmark. Two benchmark indexes are used as a basis, of which the first is a broad European equities index and the second is a similarly broad European bond index.

| Equity index | Bonds index | Start year | Allocation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pillar II pension funds | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2003 | 50%–50% |

| Pillar III pension funds | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2003 | 75%–25% |

| Data: STOXX, Bloomberg; Note: Benchmark porfolios are rebalanced annually. | ||||

For Pillar II funds, the benchmark is a 50-50 split between the two indexes, while for Pillar III a more “aggressive” allocation, with the bond index counting for 25% and the equity index counting for 75% of the Pillar II benchmark.

The equity exposure of the chosen benchmarks (50% and 75% respectively) were chosen because they roughly reflect the equity exposure of Estonian Pillar II and Pillar III investment funds in the last 3 years, based on Finantsintspektsioon data. For both pillars, the equity exposure was lower on average historically compared to recent years. 4 However, the Author considers the more recent allocation the best benchmark since it reflects the direction of travel of the Estonian pension system where successive reforms have allowed for and encouraged higher equity allocations, with the objective of increasing long-term returns.

As can be seen in Figure 9.7 and Figure 9.8, when discounted for the Estonian inflation rate, the real performance of the benchmarks correlates significantly with the performances of both Pillars II and III. However, in the long term, both pillars significantly underperform their benchmarks.

There are two likely causes for this significant underperformance: fees and asset allocation. The benchmarks show the change in the value of the underlying assets, assuming all dividends and interest payments are reinvested in the same index with no fees or charges deducted. This contrasts with the investment funds, which incur various expenses, including management fees charged by the company managing the funds. As explained in the charges section of this report, while average expenses in both pillars have fallen to relatively low levels in recent years, relatively high administration and management fees were charged for most of the period since the inception of the system, with fees starting to significantly decline only after 2013. Thus it can be assumed that eliminating the effect of charges would eliminate most of the difference between the benchmark and actual returns. In addition, as referenced before, it seems to be the case that the asset allocation for most of the period in both pillars included less equity and more exposure to bonds and other asset classes such as cash deposits and money market funds, which generally yield less in the long-term compared to equities.

9.6 Conclusions

Estonia is an early pension system reformer among the formerly communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe. The system which came fully into effect in 2003, is a typical multi-pillar pension system that combines an unfunded, defined contribution state pension (Pillar I), as well as an auto-enrolled second pillar and voluntary pillars, the latter two of which are fully funded. Different types of pension vehicles in Pillars II & III allow savers to choose from a wide variety of investment strategies. Lower transparency in fee history contrasts with the high transparency of performance disclosed on a daily basis. The exception is Pillar III insurance contracts, where no information about performance or fees is publicly disclosed, which is why this relatively least used pension vehicle was not examined in this report.

The performance volatility of most pension vehicles is relatively high. However, Estonian savers tend to accept higher risk with regard to their savings. Pillar III vehicles are a typical example of highly volatile pension vehicles. A new trend emerged in 2016 and continued into 2021—the introduction of low-cost indexed pension funds for both funded pension pillars, which could deliver higher value to savers due to lower charges compared to peers. The competitive pressure from these new low-cost funds has led to an overall decrease in fees for both Pillar II and Pillar II funds, which should increase the ability of the funds to deliver performances closer to capital-market benchmarks in future years. The increasing tendency for larger equity exposure on average in both pillars should also boost real returns in the long term.

Overall, achieving an adequate gross salary replacement ratio in retirement remains a challenge in Estonia, especially due to high inflation, which led to Pillar II real (purchasing power adjusted) returns turning negative over all time horizons until 2023 and turned slightly positive in 2024. The challenge has only become greater since 2021 after about 30% of all Pillar II pension savers withdrew their savings before retirement. This was enabled by a controversial change to the Pension system, which BETTER FINANCE strongly criticised in the past. It is a sad irony that this partial dismantling of the formerly mandatory II pension pillar was undertaken just as a combination of successive reforms and market tendencies had well-positioned Pillar II investment funds to achieve significantly higher long-term investment returns in the future.

Acronyms

- AuM

- assets under management

- EU

- European Union

- GDP

- gross domestic product

- PAYG

- pay-as-you-go

- TER

- total expense ratio

For example, this would be the case for someone starting work at 20 years of age in 2003 and retiring at 65—which according to current regulation would be the minimum pension age for someone of that cohort.↩︎

BETTER FINANCE calculation based on Pensionikeskus and Statistikaamet data.↩︎

Own calculation, based on Statistikamet data.↩︎

Estonian pension funds invest a large proportion of their Assets in other investment funds and while the available data does provide a breakdown between “equity funds” and “other investment funds”, there is no data for exactly how much equity exposure these two types of funds have. I.e. if “equity funds” might have 100%, 90% or 75% invested in equities while “other investment funds” may also have some degree of equity exposure. References to the current or historic equity exposure of Estonian pension funds reflect the Author’s best estimate given the limitations in data, but have a large and uncertain margin of error.↩︎