Product categories

|

Reporting periods

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Pillar | Earliest data | Latest data |

| Contractual pension funds | Occupational (II) | 2000 | 2024 |

| Open pension funds | Occupational (II) | 2000 | 2024 |

| PIP with profits | Voluntary (III) | 2008 | 2024 |

| PIP unit-linked | Voluntary (III) | 2008 | 2024 |

Sintesi Il sistema pensionistico italiano rimane essenzialmente organizzato attorno al suo pilastro pubblico: la pensione statale costituisce il reddito pensionistico primario e spesso l’unico; i fondi pensione complementari coprono solo una minoranza della forza lavoro italiana. Tuttavia, l’invecchiamento della popolazione e i livelli strutturalmente elevati di debito e deficit pubblico mettono a dura prova il sistema pensionistico pubblico: Una serie di riforme ha cercato di limitare l’aumento delle passività pensionistiche dello Stato e di sviluppare schemi pensionistici professionali e individuali a capitalizzazione come alternativa credibile. Queste riforme, tuttavia, non sembrano convincere gli italiani, che investono ancora relativamente poco dei loro risparmi nei fondi pensione contrattuali o aperti, o nei PIP “nuovi”, i principali strumenti di risparmio previdenziale che analizziamo in questo capitolo. L’analisi della performance di lungo periodo di questi prodotti sembra dar loro ragione: Su un periodo di 25 anni (2000–2024), i fondi pensione contrattuali riescono a offrire solo un rendimento reale netto dello +0,7%, quello dei fondi pensione aperti è negativo, pari a -0.1%, mentre le due principali categorie di PIP, i piani con “gestione separata” e i piani unit-linked, mostrano un rendimento reale netto rispettivamente dello 0,4% e dello -0,3% per cento su 17 anni (2008–2024). Un’allocazione eccessivamente conservativa degli asset e—con la relativa eccezione dei fondi pensione contrattuali—costi elevati appaiono come i principali fattori di sottoperformance in termini nominali. L’inflazione, che ha avuto un’impennata nel 2021-2022, dopo quasi un decennio di virtuale assenza, ha divorato ciò che restava dei risparmi pensionistici degli italiani.

Summary The Italian pension system remains essentially organised around its public pillar: the state pension constitutes the primary and often the only pension income; complementary pension funds cover only a minority of the Italian labour force. However, an ageing population and structurally high levels of public debt and deficit put the public pension system under strain: a series of reforms have attempted to limit the increase in state pension liabilities and to develop funded occupational and individual pension schemes as a credible alternative. These reforms, however, do not seem to convince Italians, who still invest relatively little of their savings in Contractual or open-ended pension funds, or in Piani Individuali Pensionistici (PIPs), the main retirement savings instruments that we analyse in this chapter. The analysis of the long-term performance of these products seems to prove them right: over a period of 25 years (2000–2024), Contractual pension funds manage to offer only a net real return of +0.7%, open pension funds a negative -0.1%, while the two main categories of PIPs, “with profits” plans and unit-linked plans, show a net real return of 0.4% and 0.3% respectively over 17 years (2008–2024). Overly conservative asset allocation and—with the relative exception of Contractual pension funds—high costs appear as the main drivers of underperformance in nominal terms. Inflation, which surged in 2021-2022 after almost a decade of virtual absence, devoured what was left of Italians’ pension savings.

12.1 Introduction: The Italian pension system

In this chapter about Italian private pensions, we will analyse the four product categories listed in Table 12.1. Within the occupational pillar, we will analyse separately the returns obtained by Contractual pension funds and open pension funds over 24 years (2000–2024). Our reporting period will be shorter for PIPs, the individual pension plans constituting the third pillar of the Italian pension system: we will analyse performance since 2008, distinguishing between PIPs “with profits” and “unit-linked” PIP. Whenever possible, we will also analyse available cost and performance data for sub-categories within these four products.

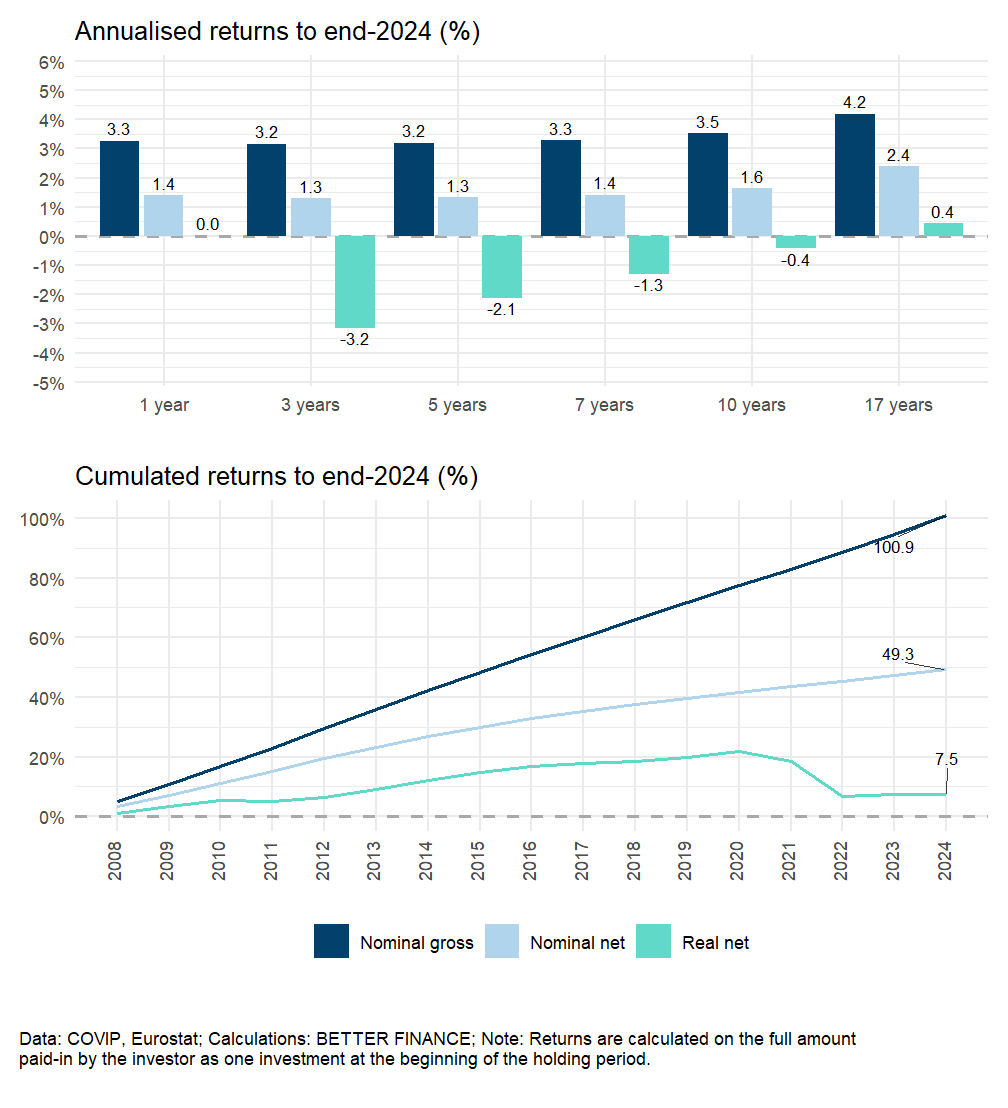

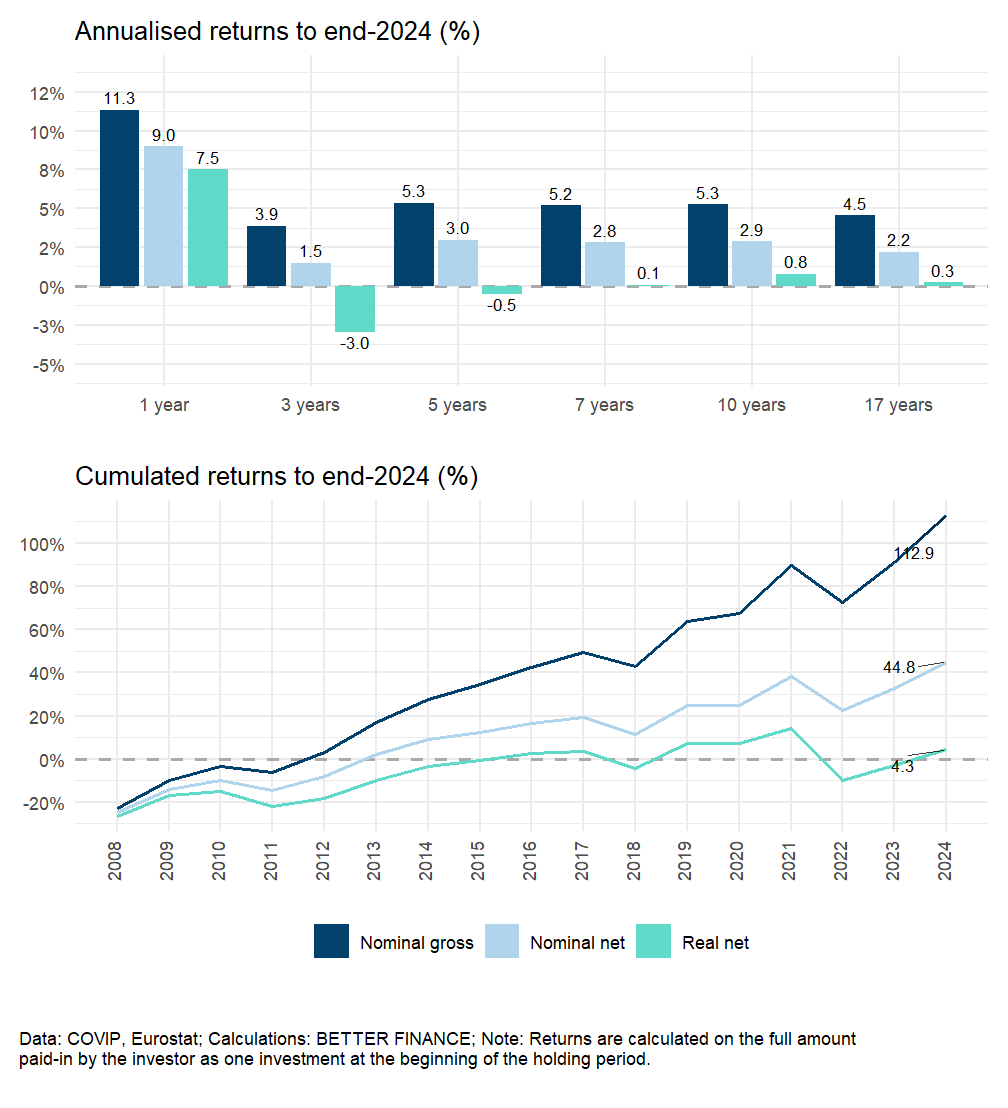

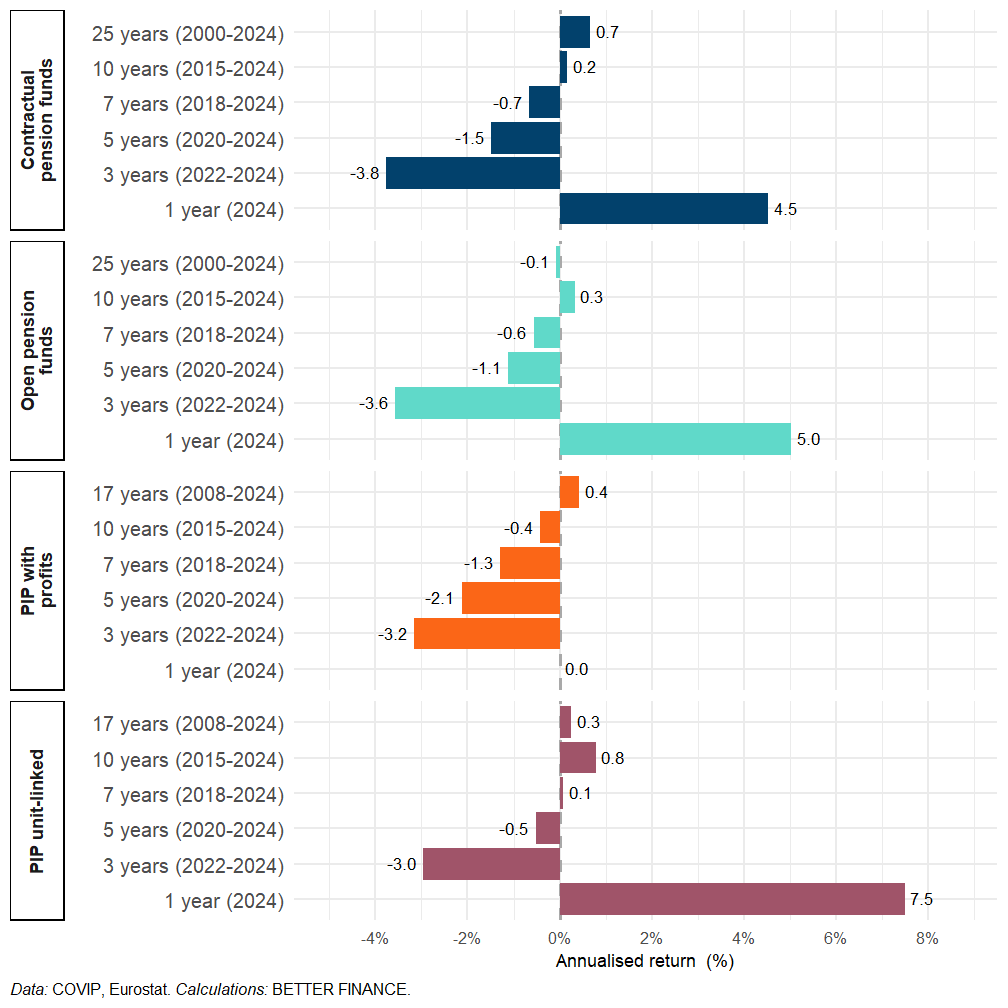

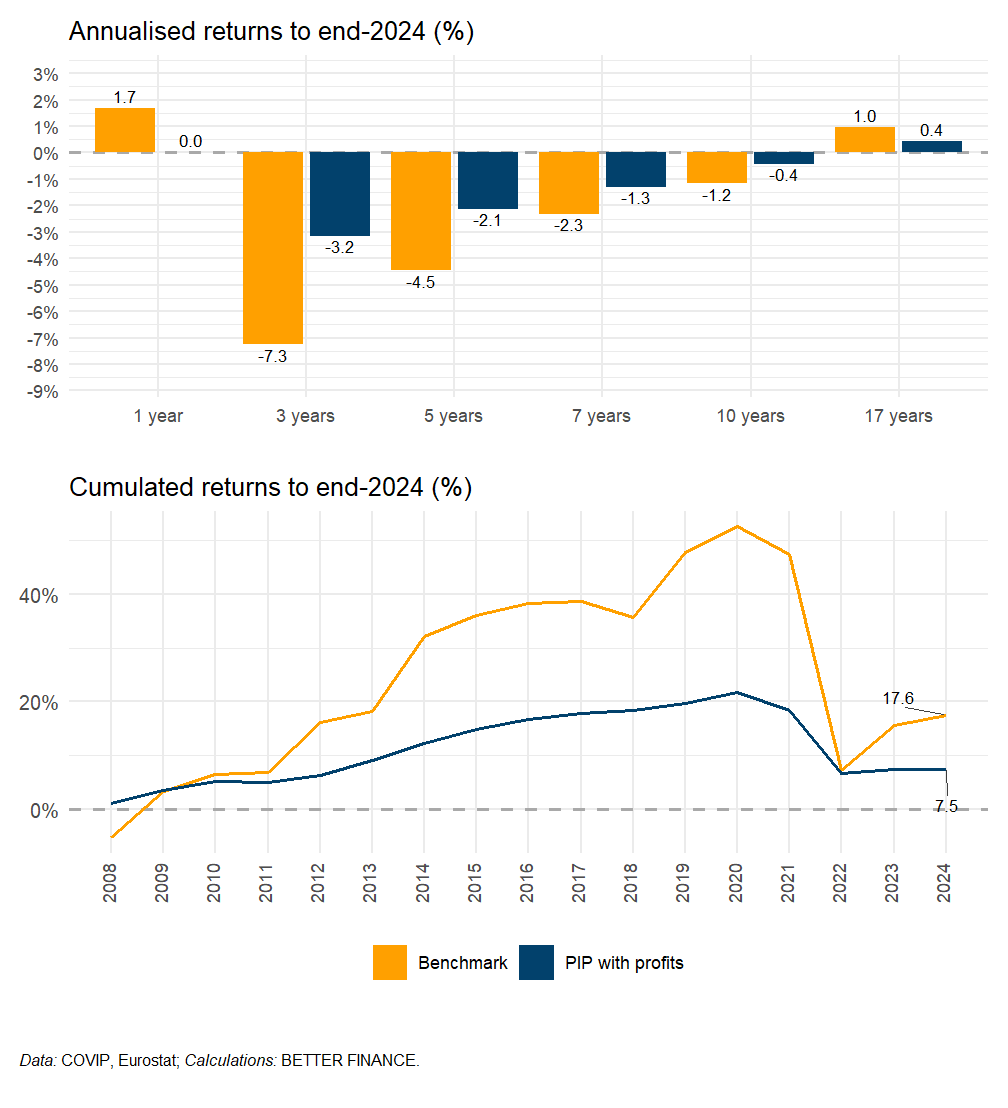

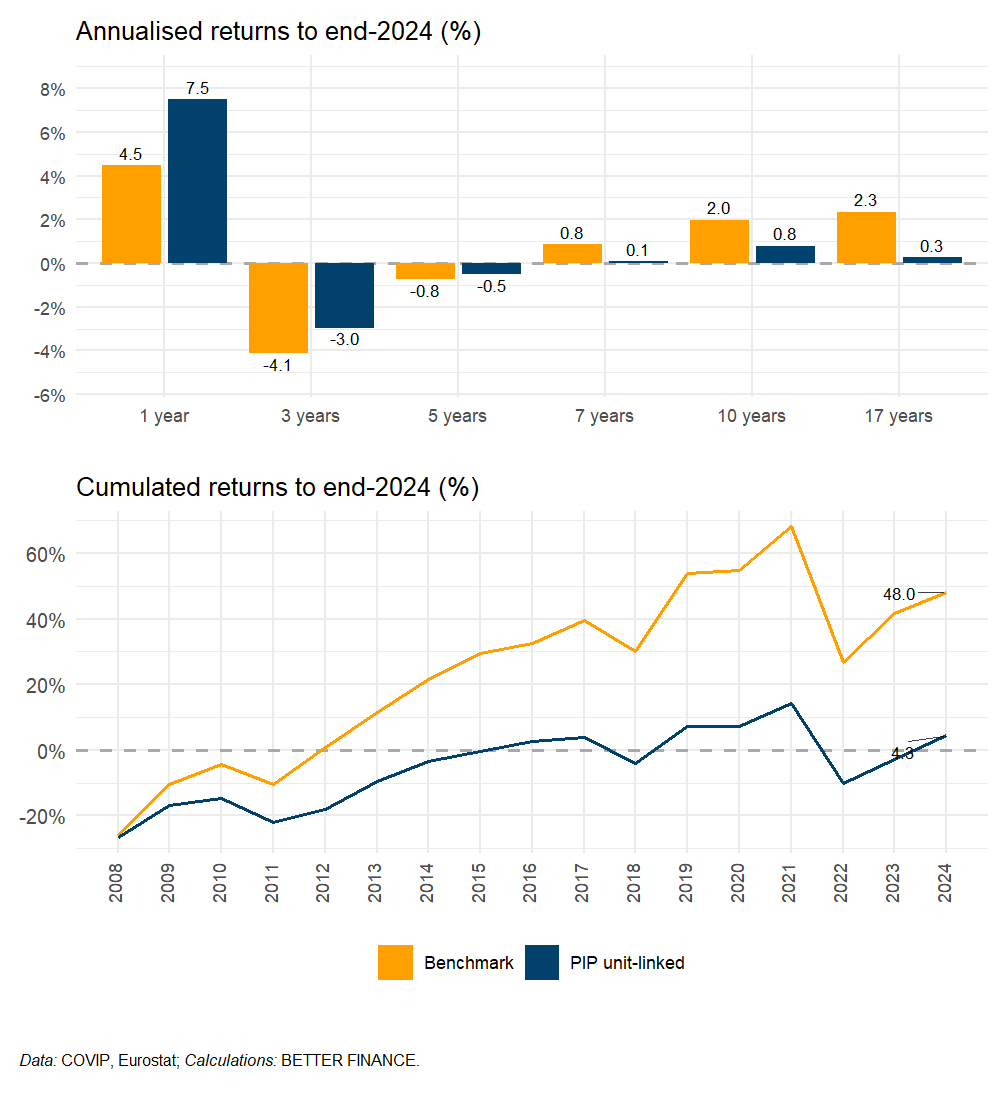

2024 was a contrasted year for Italian pension savings: As shown in Table 14.2, the 1-year returns after charges and inflation of contractual and open pension funds reached 4.5% and 5% respectively, while PIPs unit-linked returned a 7.5% gain for their participants; in the meantime, the purchasing power of savings in PIPs “with profits”—a poor name, as it turns—stagnated.

Holding period

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | 7 years | 10 years | Whole reporting period | to... | |

| Contractual pension funds | 4.5% | -3.8% | -1.5% | -0.7% | 0.2% | 0.7% | end 2024 |

| Open pension funds | 5.0% | -3.6% | -1.1% | -0.6% | 0.3% | -0.1% | end 2024 |

| PIP with profits | 0.0% | -3.2% | -2.1% | -1.3% | -0.4% | 0.4% | end 2024 |

| PIP unit-linked | 7.5% | -3.0% | -0.5% | 0.1% | 0.8% | 0.3% | end 2024 |

| Data: COVIP, Eurostat; Calculations: BETTER FINANCE | |||||||

The pluriannual real performance, however, offers a sobering perspective: over the past 25 years, Contractual pension funds barely manage to beat inflation (+0.7% real net return), Open pension funds fail to beat it (-0.1%), and since 2008 (first full year of data after inception in 2007), PIPs returned a meagre +0.4% for the “with profits” branch, while savers in PIPs unit-linked products gained a even smaller 0.3%.

In the remainder of this section, we will briefly present the Italian pension system, including its Pillar I State pension, before delving into our analysis of the four private pension categories. We will then report on the costs and charges levied on savings accumulated in these products, the fiscal regime applicable to them, before analysing their performance over the reporting period.

Pension system in Italy: An overview

The Italian pension system is organised around the classic three-pillar World Bank model:

- Pillar I is a public pension scheme managed by the Italian State;

- Pillar II is composed of occupational pension arrangements, to which enrolment is mandatory;

- Pillar III is composed of individual pension saving products, subscribed on a voluntary basis.

Both Pillar II and Pillar III pension funds and plans are supervised by .na.character (COVIP), whose data constitutes the basis of our analysis of costs and performance.

Pillar I: The State pension

The first pillar remains the main pension vehicle in Italy. It is composed of two tiers: zero and first. The zero tier consists of a social pension ensuring a minimum level of income for the elderly. The first tier covers employed individuals and for those who entered the labour market before 1995, functions as a Defined benefits (DB) system. The “Dini reform” of 1995 however changed the nature of the first tier for all those who entered the labour market after 1995: the system is now organised as a notional defined contribution (NDC) system and pension entitlements are no longer computed according to an earnings-related system (Riforma del sistema pensionistico obbligatorio e complementare (legge 335/1995) 1995).

Further reforms and adjustments of the Italian public pension system were adopted in the 2010s, in order to restore sustainability, in the context of an ageing population and massive pension expenditure. In 2011, Elsa Fornero, minister for Welfare and Social Policy under Mario Monti’s “technical” government, implemented a reform intended to bring the system close to equilibrium. The main eligibility criterion became the number of years worked rather than one’s age, with early retirement legally possible but subject to penalties. Nevertheless, the Italian Constitutional Court stated in April 2015 that the suppression of indexation of pensions on inflation included in the “Fornero law” was unconstitutional: the indexation of pensions on inflation was estimated to add EUR 500 millions to the costs of the State pension.

This judicial reversal was succeeded by the adoption of measures facilitating early retirement, such as the “Ape Sociale”, “Opzione Donna” and, most notably, the “Quota 100” measure, effective from January 1st, 2019. This measure enables employees with a minimum of 38 years of service to retire early if the combined total of their age and years of service reaches 100. The “Quota 100” has since been reviewed, becoming “Quota 102” in 2022 and “Quota 103” as per the budget law for 2024: Italians can now retire as early as 62 years old, provided they have at least 41 years of contributions. Under “Quota 103”, however, the anticipated state pension is calculated entirely based on the amounts of contributions effectively paid, and does not include any redistributive element, which could represent a substantial reduction of beneficiaries’ income Acquaviva (2023). The 2024 budget law generally tightened the conditions of access to anticipated pensions, with, for instance, early retirement windows (amount of time which one must wait to receive their first payment) extend from 3 to 7 months for private sector workers and from 6 to 9 months for public servants.

Pillar II: Occupational pensions

The second pillar of Italian pensions is composed of collective complementary pension plans. These can be “Contractual pension funds (Fondi pensione negoziali—occupational funds managed by social partners under collective bargaining agreements (CBAs)—or”open” pension funds (“Fondi pensione aperti”) constituted by various types of financial institutions, which welcome members on an individual or collective basis Commissione di Vigilanza sui Fondi Pensione (2022).

Besides pension funds, the Trattamento di Fine Rapporto (TFR) is also part of the second pillar. The TFR is a deferred indemnity: each year the employer is required to set aside a portion of the employee’s salary, to be accumulated and returned to the employee upon termination of the employment contract.

Pillar III: Voluntary individual pensions

The third pillar is composed of voluntary contributions to individual complementary pension schemes, PIP. Individuals can also make contributions to open funds in the case of individual affiliations. Given the strong component of mandatory contributions within the state pension system, both collective and individual complementary pension funds play a small role in the financing of future retirees’ income. While the savings in collective complementary pension funds are rather small, private savings are still consistent. If all pension contributions and home ownership were transformed into an annuity, the corresponding stream of generated income at retirement would be very high.

To summarise the information of the pension system set-up and to obtain a basic overview of the pension system in Italy, the table below presents key data on the multi-pillar pension system.

12.2 Pension savings vehicles in Italy

At the end of 2023, 9.953 million Italians were enrolled into at least one collective or individual pension plan (Pillar II or III), a 4% increase compared to end-2023 which brings the coverage ratio of Italian supplementary pensions to 38.3%, a modest though growing number. Especially if we deduct the members who have not made a contribution in 2024: the coverage ratio in term of active participants is then only 27.6%. Pension assets managed by the sector grew 8.5% in 2024, reaching EUR 243.3 billion, i.e., 11% of the Italian gross domestic product (GDP) and 4% of the financial assets of Italian households (Commissione di Vigilanza sui Fondi Pensione 2025).

Figure 12.1 displays the total amounts of savings in the four product categories here analysed. As we can see from this figure, Contractual pension funds within Pillar II and PIPs with profits within Pillar III are the two categories of products which increased fastest, in terms of accumulated capital. With EUR 74.6 billion in assets under management (AuM) at end-2024 stand as the main retirement savings vehicle in Italy. Open funds and PIP with profits still see a steady growth of AuM to EUR 37.3 billion and EUR 37.7 bln. PIP unit-linked seem less popular, though in constant growth, with EUR 17 billion in AuM at end 2023.

Over the twenty-five years covered in our report, the number of pension funds and plans on offer in Italy was reduced dramatically: From 739 funds and plans in operation in 1999, only 291 remained active at the end of 2024 (down from 302 at end-2023). As the supervisor, COVIP explains:

The number of pension schemes has been steadily declining for over twenty years: in 1999, there were 739 schemes operating within the system. In particular, the number of pre-existing funds fell by 467, including ten in the last year. These funds continue to be affected by reorganisation and consolidation in the financial sector, with the formation of banking and insurance groups within which various supplementary pension schemes for employees of individual banks and insurance companies coexisted. These schemes have often been merged into one or two group funds.

The concentration trend particularly affected the “pre-existing” funds, and to a lesser extent Contractual and open pension funds. The number of PIP nuovi, individual pension plans introduced in 2007, remained relatively stable

Complementary pension funds were introduced in 1993 and are composed of Contractual funds, open funds and individual pension plans provided by life insurance companies. The main features of complementary pension plans are:

- Membership is voluntary;

- Pensions are funded;

- Schemes are managed by banks, insurance companies or specialised financial institutions;

- Their supervision is ensured by COVIP.

Following the signature of a CBA, all complementary pension funds are managed by an external financial institution that can only be an insurance company, a bank or a registered asset management company (Legislative Decree 252/2005). All complementary pension funds now operate on a Defined contributions (DC) basis, as this is the only permitted type of pension plan.

DB plans are restricted to older funds, that existed before the transition to the DC model (“Pre-existing” funds). The budget law of December 11th, 2016 allows members of complementary defined contribution pension funds, who are close to retirement age, to receive early retirement income from their accumulated savings in whole or in part; the scheme is called Rendita Integrativa Temporanea Anticipata (RITA).Eligible employees are those who benefit from a similar provision in the first pillar, the APE Sociale. To be eligible for RITA, an individual must:

- cease their professional activity;

- reach the requirements necessary to receive the old-age pension in their mandatory regime within the next five years or to be unemployed for more than 24 months;

- have contributed at least 20 complete years to the mandatory regime; or / and have completed five years in the pension scheme.

The individual determines the amount of the accrued capital to use until their official retirement. The RITA is also offered to people who have been unemployed for at least two years before their request for withdrawal and are within ten years of the statutory retirement age.

Second pillar: Contractual and open pension funds

Three types of funds exist within the occupational pillar:

- “Contractual”, also called “closed” funds, membership in which is restricted to specific groups of workers;

- “Open” funds, which are open to all;

- “Pre-existing” funds—that is, funds that existed before the Italian legislator regulated the form of Italian private pensions—are still operating and can accept as new members the employees of the firm(s) or economic sector for which they have been established, although no new such fund can be created.

Contractual funds are also called closed funds due to their restrictive membership criteria: only firms from the economic sector for which the fund was established can join in. Generally, Contractual funds are established for employees whose contract is regulated by a CBA; for the self-employed, Contractual funds are usually provided by professional associations, and consequently reserved to their members. At the end of 2024, Contractual funds had 4.108 million members.

Contractual funds’ assets are legally separated from those of the sponsor company or association, being therefore protected from creditors’ claims in case of bankruptcy of the employer. A Contractual fund must place its assets under the custody of an authorised depository (bank or investment firm). The fund’s Board of Directors is responsible for defining the investment strategy and choosing the investment manager, the depositary bank and the entity designated to administer the pensions. The fund must report at least on an annual basis. Managers’ mandates usually last five years or more, in line with the long-term orientation of funds.

Open funds, by contrast, do not restrict membership: they are set up by banks, insurance companies, asset management companies and stock brokerage firms for anyone to join on a collective or individual basis. Employees of the public sector, as well as self-employed and liberal professions can only join on an individual basis; other employees can join individually, but collective membership is also possible where provided for by a company or sectoral agreement. At the end of 2024, open funds had a little over 2 million members, 36 024 of which were also members of at least one other open fund and 121 092 had a PIP nuovo.

The assets of open pension funds are legally separated from those of the financial companies that set them up and are thus protected, in case of the company’s bankruptcy, from the claims of any creditors. Like Contractual pension funds, open funds must have an authorised depositary bank and can outsource administration.

Italians benefit since 1982 from the TFR, a severance payment system whereby the employer pays a portion of the employee’s annual salary into a specific vehicle for asset accumulation, the TFR. If an employee decides to opt-out of complementary pension funds and belongs to a company with more than 50 employees, their accumulated amount of severance payments is transferred to Instituto Nazionale Previdenza Sociale (INPS), the national social security institute, which, by law, manages the severance payment. For an employee who works in a firm with less than 50 employees and who does not opt for complementary pension funds, their TFR remains with the firm they work at and represents a debt for the company.

The accumulated amounts are mandatorily saved and can only be paid upon termination of the work contract (whatever the reason of the termination). In exceptional cases (health issues, first-house purchases, parental leave), the TFR can be partially drawn, up to 70% of the accumulated amount. The TFR is revalued annually at a rate of 1.5% plus a variable part indexed on the national inflation rate calculated by the national statistics office (Istat). In 2022, as a positive side effect of soaring inflation, the TFR’s rate rose to 8.3%,

As an alternative, since 2007 and entry into force of Legislative Decree 252/2005, each employee can individually opt to have their TFR paid into a complementary pension fund. For specific sectors where a Contractual pension fund exists, tacit consent applies for the TFR to be transferred to the fund instead of remaining with the company.

The introduction of Contractual and open funds, and the possibility to place one’s TFR with them was a significant novelty in the Italian pension landscape, which had been thus far almost exclusively organised around the State pension. Workers now had to make decisions regarding where and how to invest the portion of their income they wish—or, rather, must—save for future retirement income.

The coverage of public employees by specific retirement products is very limited, as the law introducing pension funds excluded them. Contractual pension funds are only possible for individuals working in National Education (Espero), in the National Health system and in a regional or local authority (Perseo and Sirio). These Contractual pension funds were implemented in 1993.

In terms of allocation of pension savers’ assets, both Contractual and open pension funds implement conservative investment policies, as shown in Figure 12.2 and Figure 12.3. Contractual pension funds typically invest less than a quarter of their assets into equity vs. close to 60% in debt securities. Open pension funds are less conservative, with only half of their AuM invested either in cash or bonds, but their direct equity exposure, amounting to 25.1% of assets in 2024, remains low.

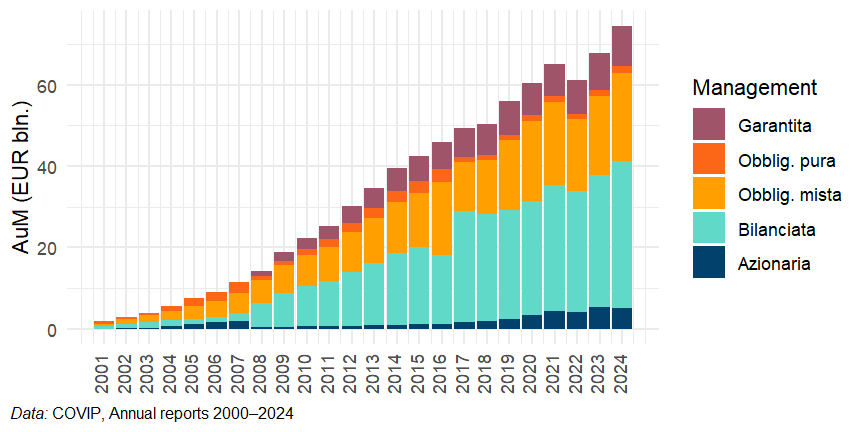

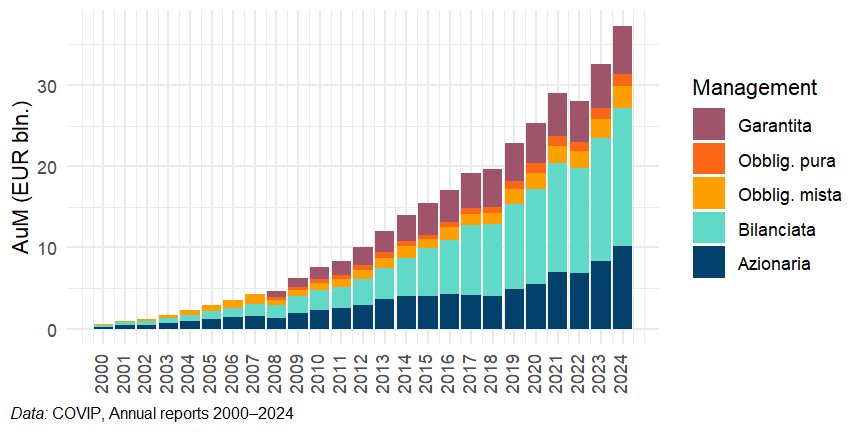

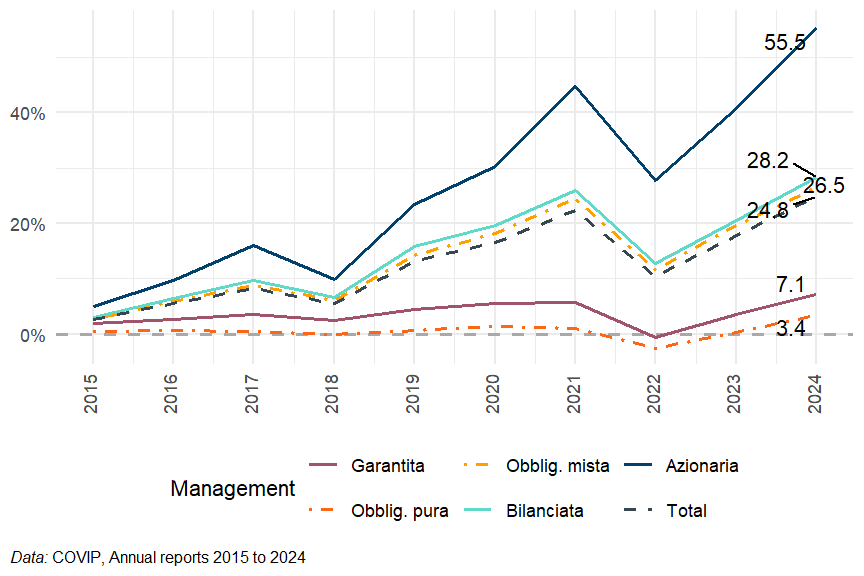

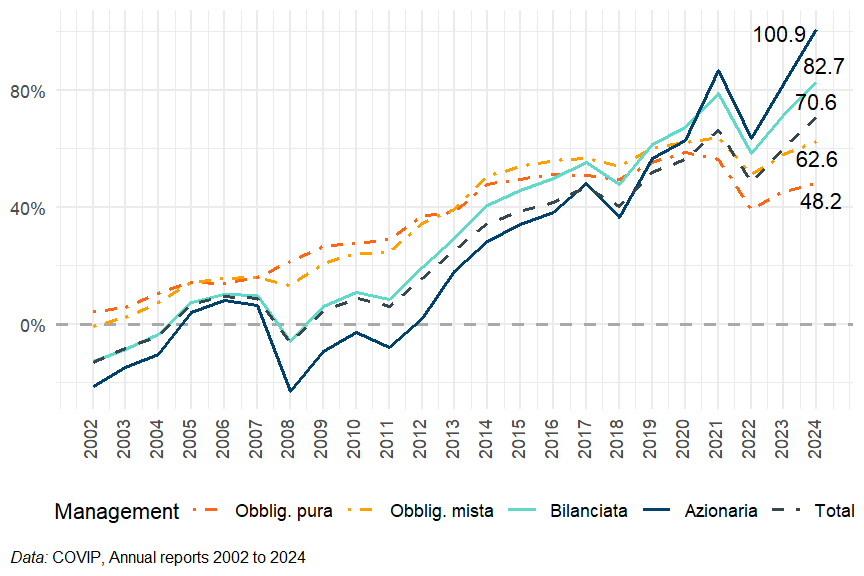

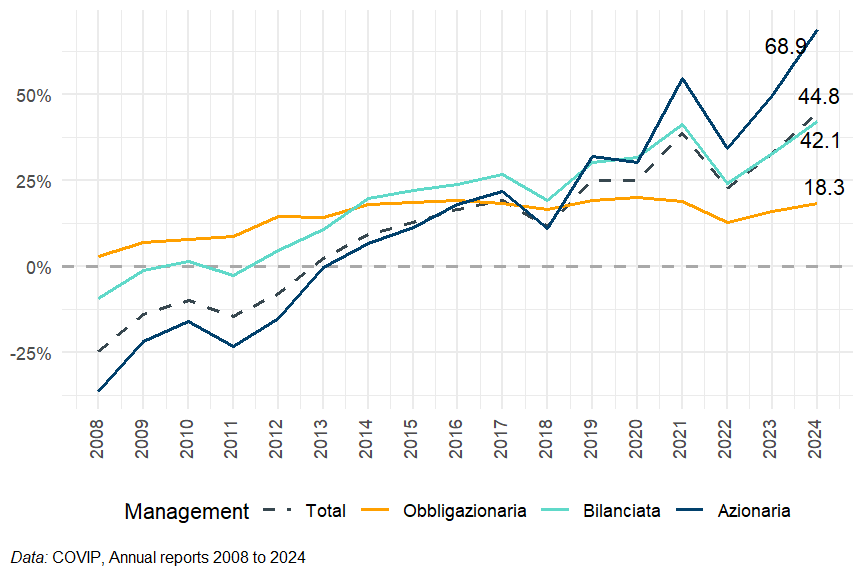

We should, however, refine this broadbrush picture: Investors in both Contractual and Open pension funds can indeed choose among different types of “management” (gestione, see above), each of these types of management offering a different degree of equity exposure. Figure 12.4 and Figure 12.5 show the distribution of total AuM of Contractual and Open pension funds, respectively, in the five types of management on offer to Italian pension savers, from the most conservative gestione obbligazionaria pura and gestione garantita, which invest none or little of their assets into equity, to the most “aggressive” gestione azionaria, where assets are mainly invested in equity. We can see that the most popular option in both categories of funds is the gestione bilanciata, which supposedly invests equally in equity and bonds, which nuances to some extent the initial impression of conservatism of Italian pension savers.

The total—direct plus indirect through investments in funds—equity exposures of the gestione azionaria was 60.3% in Contractual pension funds in 2024, down 0.2percentage points (p.p.s) from 2023, and 78.7% in Open pension funds, up 0.2p.p.s. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the gestione garantita compartments in Contractual funds and Open funds had a 5.6% and 5.5% total equity exposure, respectively. The equity exposure the gestione bilanciata—the middle ground option—was 33.7% in Contractual funds (+2.9 p.p.) and 41.5% in Open funds (+0.3 p.p.). The choice of a management option, therefore, induces substantial differences in terms of financial returns for investors in Contractual and Open pension funds (see Section 12.5.1.1).

Third pillar

PIP are individual pension plans offered by insurance companies. Their main purpose, according to the Italian committee for financial education includes but is not limited to pension savings: they can also be used to accumulate savings for major projects or unforeseen events. Anticipated withdrawals are therefore possible in case to pay for extraordinary health expenses, for first-home purchase and renovation, or for “personal and family motives”, the latter two only after an 8-year holding period (Comitato per la programmazione e il coordinamento delle attività di educazione finanziaria 2023). An anticipated pension may also be requested as per the RITA framework. Full withdrawals are also possible in case of permanent invalidity, unemployment longer than 48 months, resignation or dismissal and, of course, death of the investor.

Two main types of contracts are offered: gestione separata (“with profit”, 69% of AuM in PIP nuovi in 2024 (down from 74.6% in 2022) or unit-linked (31%, up from 25.1% in 2022). The with-profits policies guarantee a minimum rate of return (guaranteed and consolidated in the company’s accounts) which is added to a quota related to the financial performance. The unit-linked policies do not have a guarantee. Their performance depends on the value of the units in which contributions are invested.

Assets are allocated very differently under the two types of PIP nuovi, as shown in Figure 12.6 and fig-it-pipul-alloc. PIP with profits are massively invested in debt securities (85% in 2024, of which 31.3% in Italian government bonds) and virtually do not invest in equities (1.9% in 2024, down from 2.4% in 2022). By contrast, in PIP nuovi unit-linked, equity represents 39% of investments on average, while debt securities only account for 22.5% of AuM. We note that investment funds

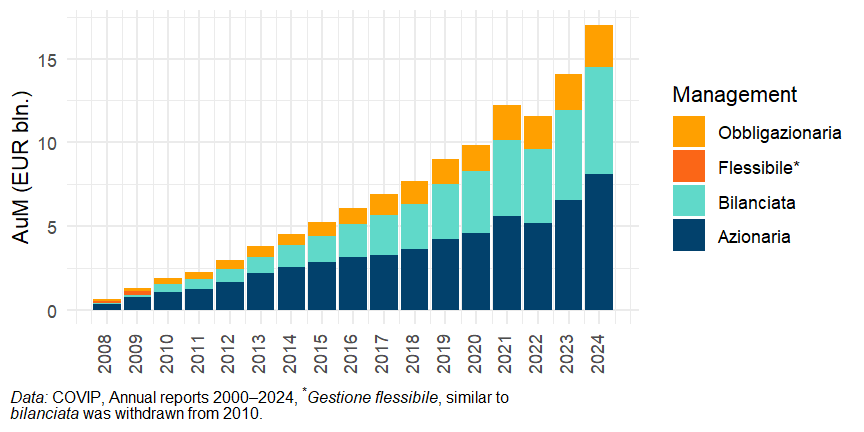

We should further note that the allocation of assets varies within the unit-linked category, where there exists three main sub-types: the already described gestione obbligazionaria, gestione bilanciata and gestione azionaria. In the obbligazionaria 73.7% of assets are invested in government bonds (72.4% in 2023) and nothing in equity. By contrast, in the gestione azionaria, assets are invested for more than 70% in direct equity holdings (72.5% in 2024) and only a tiny fraction of assets are invested in debt securities (3.5% in 2024). As we can see in Figure 12.8, gestione azionaria is the most popular of the three options in PIP nuovi unit-linked: Though it represents less than half of the smallest of the four product categories analysed in this chapter, we can see here a decidedly equity-oriented segment of Italian pension savers.

12.3 Charges

COVIP calculates a synthetic indicator of costs—Indicatore Sintetico dei Costi (ISC)—for a member who contributes EUR 2500 every year with a theoretical annual return of 4%, over increasing periods of 2 to 35 years. The calculation methodology of the indicator was revised by COVIP in order to eliminate distortions between the categories of funds. Since 2014, the tax rates on investment revenues depend on the underlying assets of the funds. Since March 2015, the cost indicator is no longer calculated net but gross of the tax paid by pension funds on their revenues. Table 12.4 shows the average, maximum and minimum values of this ISC in 2024 for Contractual and Open pension funds, as well as for all PIPs nuovi.

| Statistic | 2 years | 5 years | 10 years | 35 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contractual funds | ||||

| Maximum | 2.98% | 1.45% | 1.21% | 1.09% |

| Average | 1.12% | 0.65% | 0.49% | 0.36% |

| Minimum | 0.34% | 0.22% | 0.14% | 0.06% |

| Open funds | ||||

| Maximum | 4.73% | 3.20% | 2.58% | 2.31% |

| Average | 2.32% | 1.56% | 1.35% | 1.23% |

| Minimum | 0.55% | 0.55% | 0.55% | 0.55% |

| PIP nuovi | ||||

| Maximum | 6.44% | 4.82% | 4.07% | 3.44% |

| Average | 3.73% | 2.60% | 2.17% | 1.82% |

| Minimum | 1.04% | 0.85% | 0.58% | 0.38% |

| Data: COVIP, Annual reports 2000–2024 | ||||

As we can see, there is a great variation among pension funds in terms of costs, both between and within categories of funds. Savers should therefore be very attentive to the cost information provided by fund managers before making investment decisions. The cost indicator decreases significantly with the membership period, as initial fixed costs are progressively amortised: the drop in average costs between 2 years and 35 years is 0.76 p.p. for Contractual funds, 1.09 p.p. for open funds, and even 1.91 p.p. for PIP nuovi.

There are significant differences between each category of funds and plans, depending on the distribution channels of the products and the fees paid to distributors. Economies of scale lead to lower costs for closed funds while no such impact can be observed on new PIP and open funds, according to a review of individual figures by COVIP.

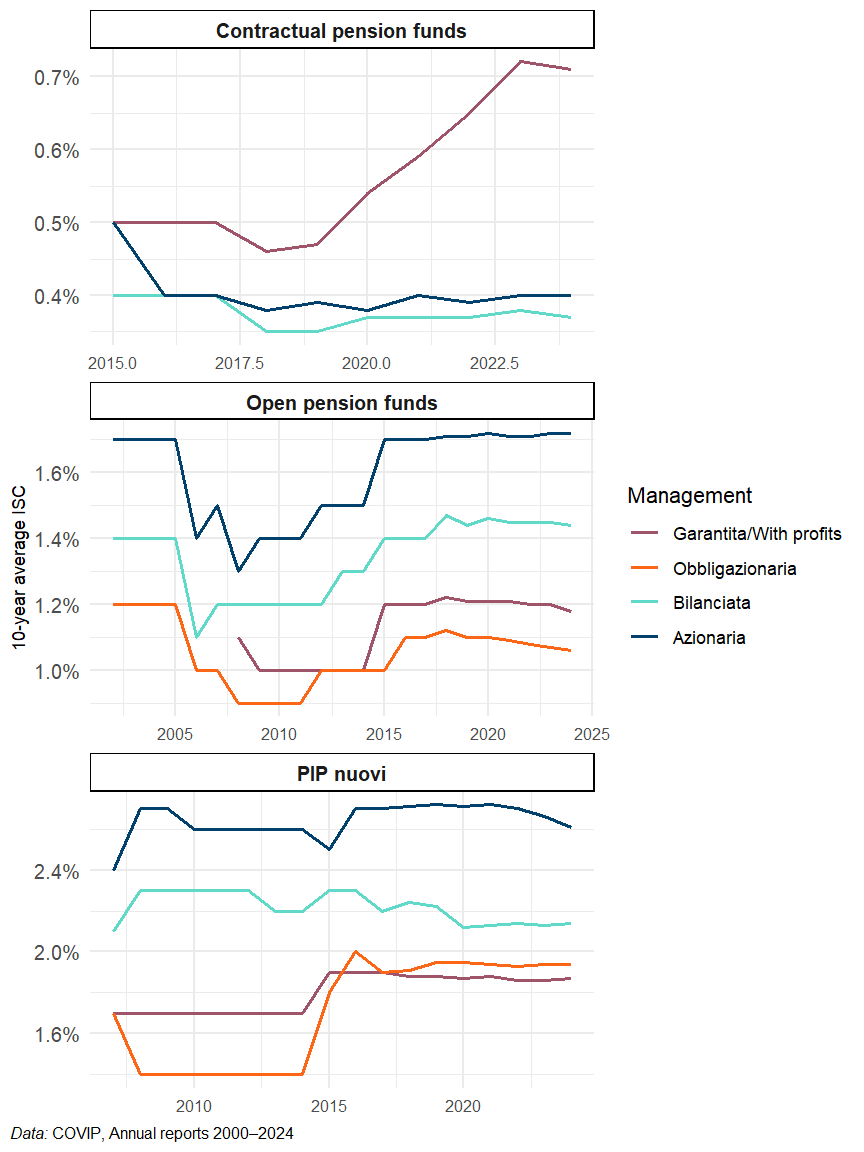

For the long-term returns calculations in this report, we retain the 10-year ISC as the cost figure to calculate the nominal net returns of each of our product categories.

COVIP also shows ISC figures for management compartments within each category of product. Figure 12.9 thus shows not only the structurally higher costs of PIPs nuovi over both Open and Contractual funds, it also shows that for both Open funds and PIP, equiy-oriented management is significantly more expensive than bond-oriented management. Interestingly, though, the pattern is reversed for Contractual funds: in those funds, which have generally much lower cost figures, the cost of equity compartments has remained low (around 0.4% since 2016), and lower than the cost of guaranteed management, which has soared.1

12.4 Taxation

The taxation regime of pension savings in Italy is essentially an ETT regime (exempt, taxed, taxed), corresponding to the following three stages over time: contribution, accumulation and payment. In the first phase, employee contributions to private pension funds benefit from a favourable tax treatment. Employees can deduct their own contributions from their taxable income up to a ceiling of EUR 5164.57 per year. Employer contributions are considered as employment income and are thus subject to tax and social security contributions.

Until 2014, in the second phase a tax rate of 11.5% was applied on the accrued capital gains paid by complementary pension funds. Since January 1st, 2015, this tax rate increased to 20%, except for accrued capital gains generated by investments in Government Bonds which are taxed at a rate of 12.5%. The difference in taxation rates of bonds and equities is an incentive to change the asset allocation towards the former, a trend that is likely to lower the returns of pension products in the future. The budget law of December 31st, 2016 foresaw that assets invested in European equities or European investment funds (up to 5% of the fund’s total assets) were exempted from income tax.

In order to avoid double taxation, benefits are taxed only on the corresponding shares that were not taxed during the accumulation phase. Contributions that were not deducted, and thus already taxed, won’t be taxed again.

In the third phase the corresponding benefits are taxed at a rate ranging between 9% and 15%, depending on the length of membership in the private pension funds. Income received before retirement age in the framework of the RITA scheme is taxed at 15%, reduced by 0.3% for each year over the fifteenth year of participation in supplementary pension schemes, with a maximum reduction limit of six percentage points. If years of enrolment in the supplementary pension scheme are prior to 2007, those years can be considered up to a maximum of 15 years. The tax rate of pension benefits that come from TFR varies between 9% and 15%, depending on the length of enrolment in the complementary pension funds.

| Product categories |

Phase

|

Fiscal Regime | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contributions | Investment returns | Payouts | ||

| Contractual pension funds | Exempted | Taxed | Taxed | ETT |

| Open pension funds | Exempted | Taxed | Taxed | ETT |

| PIP with profits | Exempted | Taxed | Taxed | ETT |

| PIP unit-linked | Exempted | Taxed | Taxed | ETT |

| Source: BETTER FINANCE own elaboration, based on Comitato per la programmazione e il coordinamento delle attività di educazione finanziaria, 2023. | ||||

12.5 Performance of Italian long-term and pension savings

Real net returns of Contractual and Open pension funds and PIP nuovi

In this section, based on data from Commissione di Vigilanza sui Fondi Pensione (2025) and previous years, we analyse the nominal returns obtained by Contractual pension funds and open pension funds since 2000 and the two main types of PIP nuovi since 2008 (the first full year of operation for these products), and compute real net returns, that is, after charges and inflation, over these periods.

As already mentioned, in order to calculate the long-term net returns, we deduct annual costs from each year’s nominal gross return figure. For that operation in the Italian case, we take for each year and each product category the average value of COVIP’s synthetic cost indicator for a 35 year period (see Table 12.4).

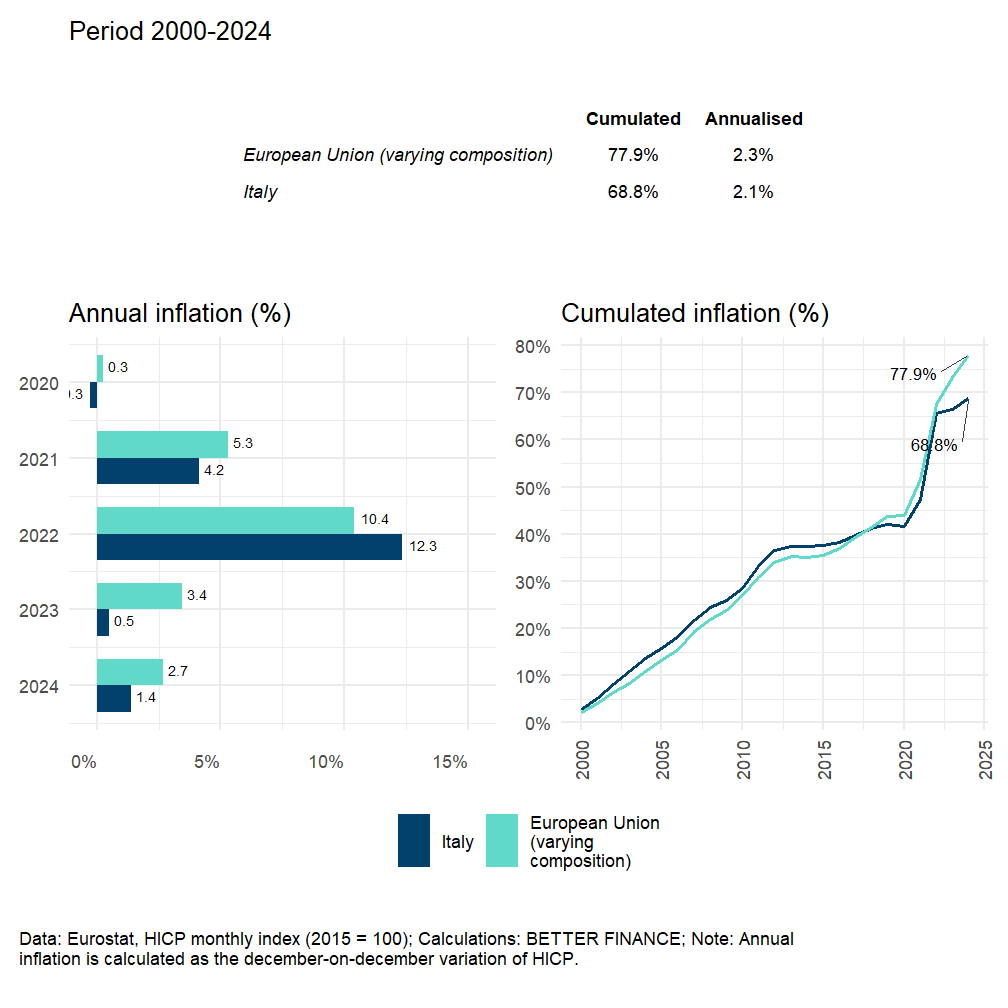

In order to correct the nominal net returns for inflation, we calculated the annual inflation rate in Italy since 2000, based on Eurostat’s harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) (see methodology in Section 3.2). As can be seen from Figure 12.10, in terms of inflation, Italy was below the European Union (EU) average over the period 2000-2024, with a 2.1% annual average and a 68.8% cumulated. In 2022 inflation climbed to 12.3%, 1.9 p.p. above the EU average (10.4%) but fell to a mere 0.5% in 2023, 2.9 p.p.s below the EU average for that year. With 1.4% in 2024, Italy seems to be back to its normal, low-inflation situation.

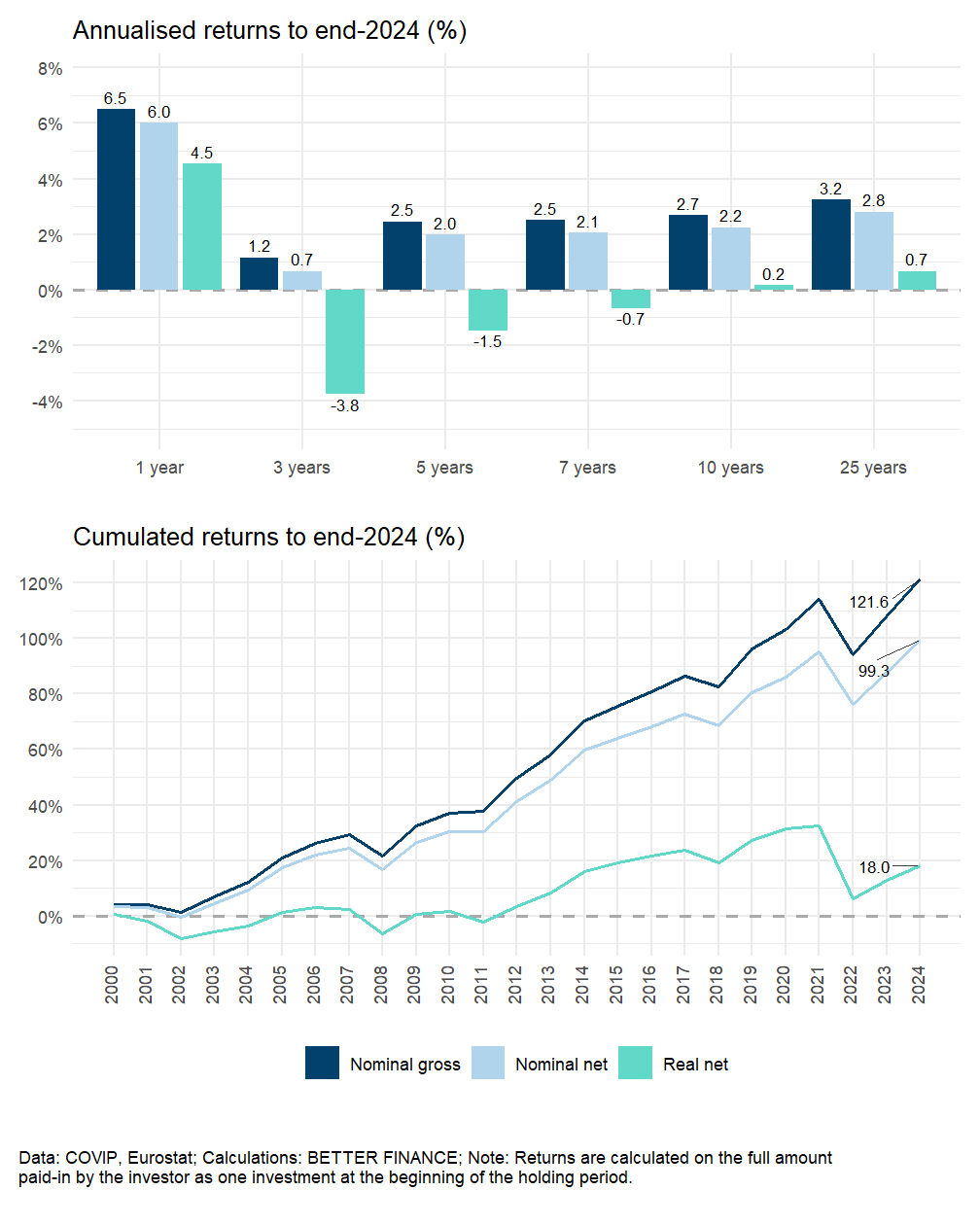

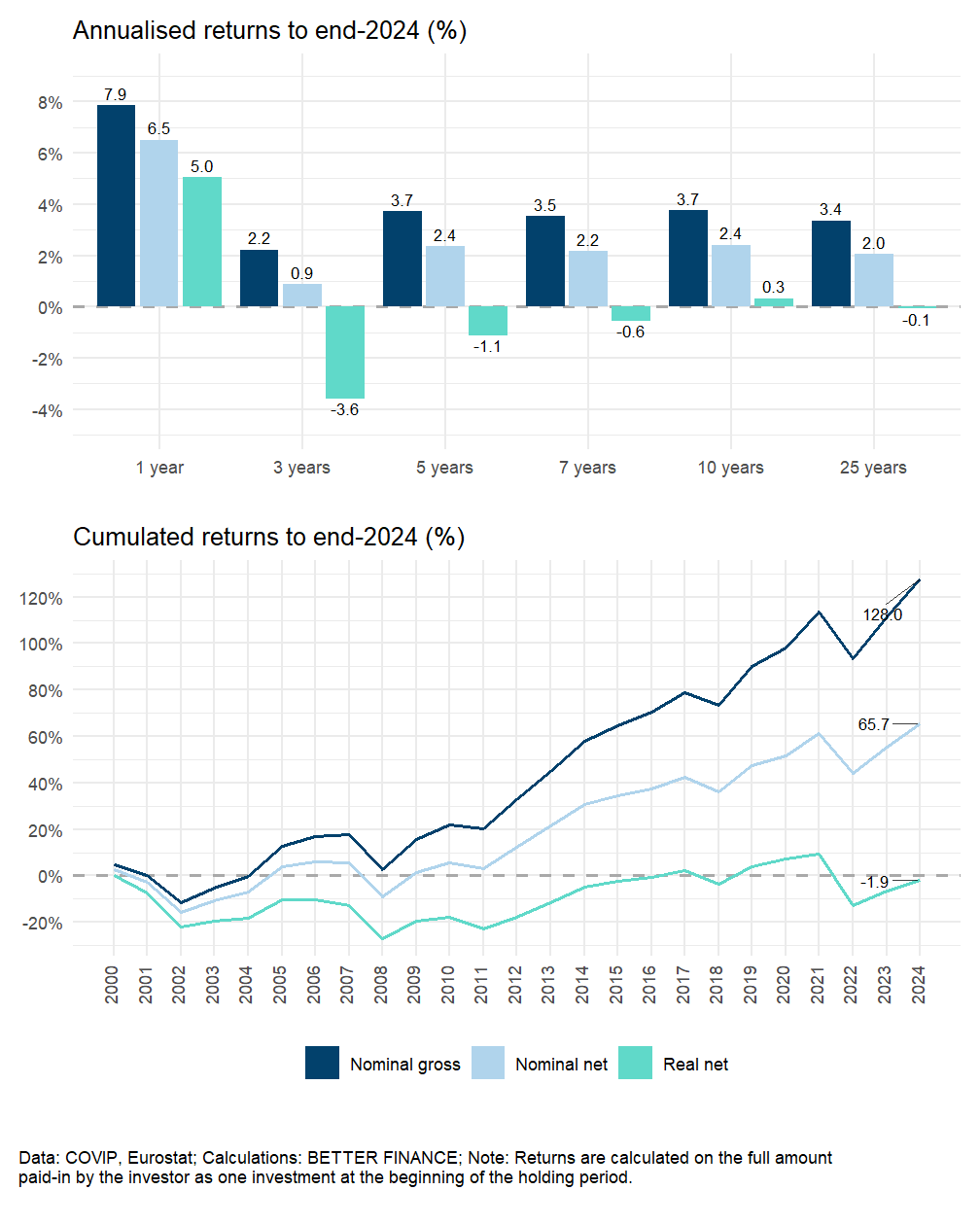

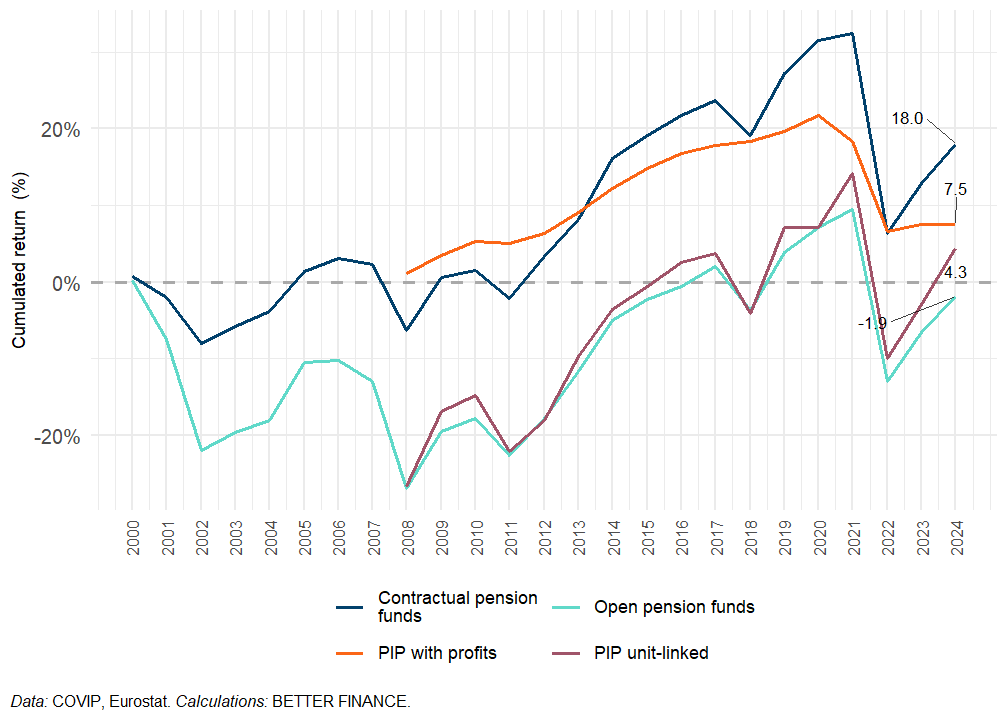

Performance of Contractual and Open pension funds

Figure 12.11 and Figure 12.12 show the nominal gross, nominal net and real net returns of Contractual and Open pension funds. Even before the inflation hike of 2021-2022, the long-term real performance of these products attests to the eroding effect of inflation on investment returns: over 25 years, inflation reduced the cumulated performance of Contractual pension funds by 81.2 p.p., and that of Open pension funds by 67.5 p.p., turning the later negative at -1.9%. Therefore, Italian workers who may be under the illusion that the value of their pension savings almost doubled over the past two decades have actually gained very little purchasing power if investing in Contractual funds, and actually lost purchasing power if investing in Open pension funds.

The results of Open pension funds furthermore show the long-term impact of costs: While nominal returns before charges are similar and even superior to those of Contractual pension funds (128% vs. 121.6% over the period 2000-2025), the higher average 10-year synthetic cost indicator of Open pension funds results in a nominal net performance 33.6 p.p.s lower than that of Contractual funds.

Disaggregating these return figures in Figure 12.13 and Figure 12.14, we can see that the nominal performance of the gestione azionaria is, over the period, widely superior to that of the conservative options in both Contractual and Open pension funds, and that despite the higher costs attached to equity management in Open funds (see above).

[1] 2052.9

Over the ten years of data available for Contractual funds’ compartments (2015–2024), with a 55.5% cumulated nominal net return gestione azionaria outperforms the second best-performing option, gestione bilanciata, by more than 20 p.p.s and the most conservative obbligazionaria pura, which barely returns a positive performance, by 52.1 p.p.s. Over 23 years, the gestione azionaria of Open funds outperforms the average of compartments by 30.3 p.p.s and the most conservative option obbligazionaria pura by 52.7 p.p., respectively. Here is a perfect illustration of the higher returns that investors may expect from a higher degree of equity exposure.

Performance of PIP nuovi

We can appreciate in Figure 12.15 and Figure 12.16 the major impact of fees on the performance of Italian PIPs. Costs eat away approximately half of the long-term performance of PIPs with profit and unit-linked. Inflation, modest as it may be in Italy, swipes away the rest of the performance, for a real net return that hardly turns positive after 7 years for the unit-linked version, and after more than 10 years for PIPs with profit. It is particularly striking that, in a year—2024—that has been rather good for capital markets, with a +7% performance for bonds, PIP “with profits” yielded a null return after costs and inflation.

For the unit-linked PIPs, however, the breakdown of performance (after charges, before inflation) by type of management reveals, here again, highly diverging trajectories across the different types of “compartments”.2 As we can see from Figure 12.17, there is a world between the +68.9 nominal net return of the gestione azionaria, the version with the greates equity exposure, cumulated over 17 years, and the paltry +18.3% nominal return of the gestione obbligazionaria over the same period.

The difference in long-term performance is even more striking when considering where both types of compartments started from. With a greater exposure to equity markets, the azionaria started off in 2008—the year of the Global Financial Crisis—with a major slump, yielding a frightful -36.5%, from which it recovered strongly: from this 2008 low, its cumulated nominal net performance is thus 105.4%, despite strongly negative returns in 2011, 2018 and 2022. By contrast, the apparent safety of the obbligazionaria—it offered a positive return every year except for a slightly negative performance in 2018 and a somewhat bigger fall in 2022—hides the ugly truth that a +18.3 nominal net performance is certain to translate into a loss of purchasing power once inflation is accounted for.

Retuns in comparison

In the face of it, Italians do not seem very well served by their supplementary pensions. No wonder only a minority of them entrust their savings to Pillar II and III and rely on alternative savings channels instead (not that this is necessarily a good idea either…). Bringing together the return figures of the four main categories of products we analysed in this chapter, we see in Figure 12.18 that the annualised long-term real net returns (over 25 years for Contractual and Open pension funds, over 17 years for PIPs) are all below 1%, even negative for Open funds.

The story told by Figure 12.19 is the same: were Italian pension savigns vehicles offering good returns—the kind of returns on which one can rely on for one’s retirement income—the curves on this graphs should slope upwards. They clearly do not. Ups and downs, and a good dose of stagnation, with a deep dive in 2022 which we hope will be followed by a rapid recovery.

Nevertheless, there is hope for Italian supplementary pensions. As we have seen in Figure 12.13, Figure 12.14 and Figure 12.17, the compartments of these products with a greater exposure to equity markets have had a strong performance over the past two decades, managing to pass on to investors the good performance of the underlying equity markets.

Do Italian pension savings products beat capital markets?

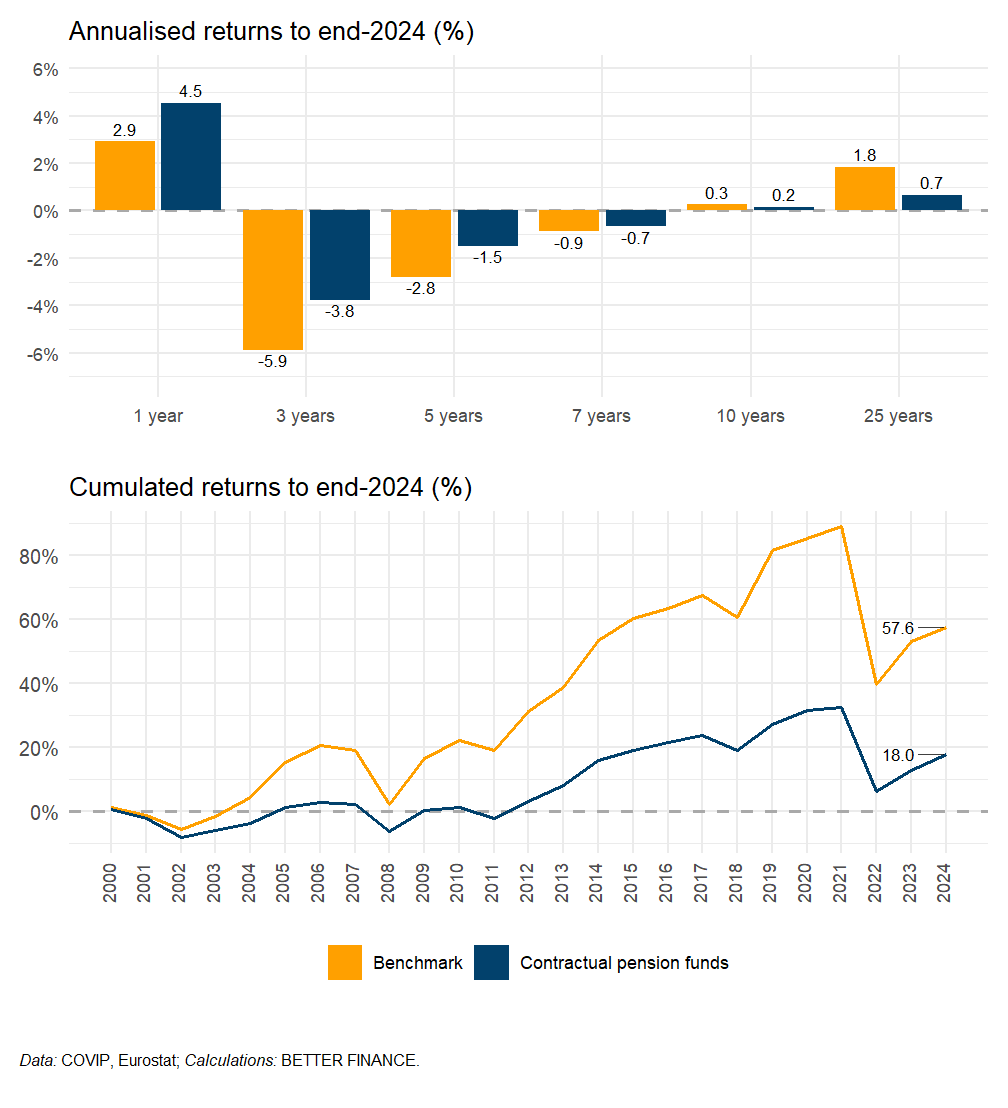

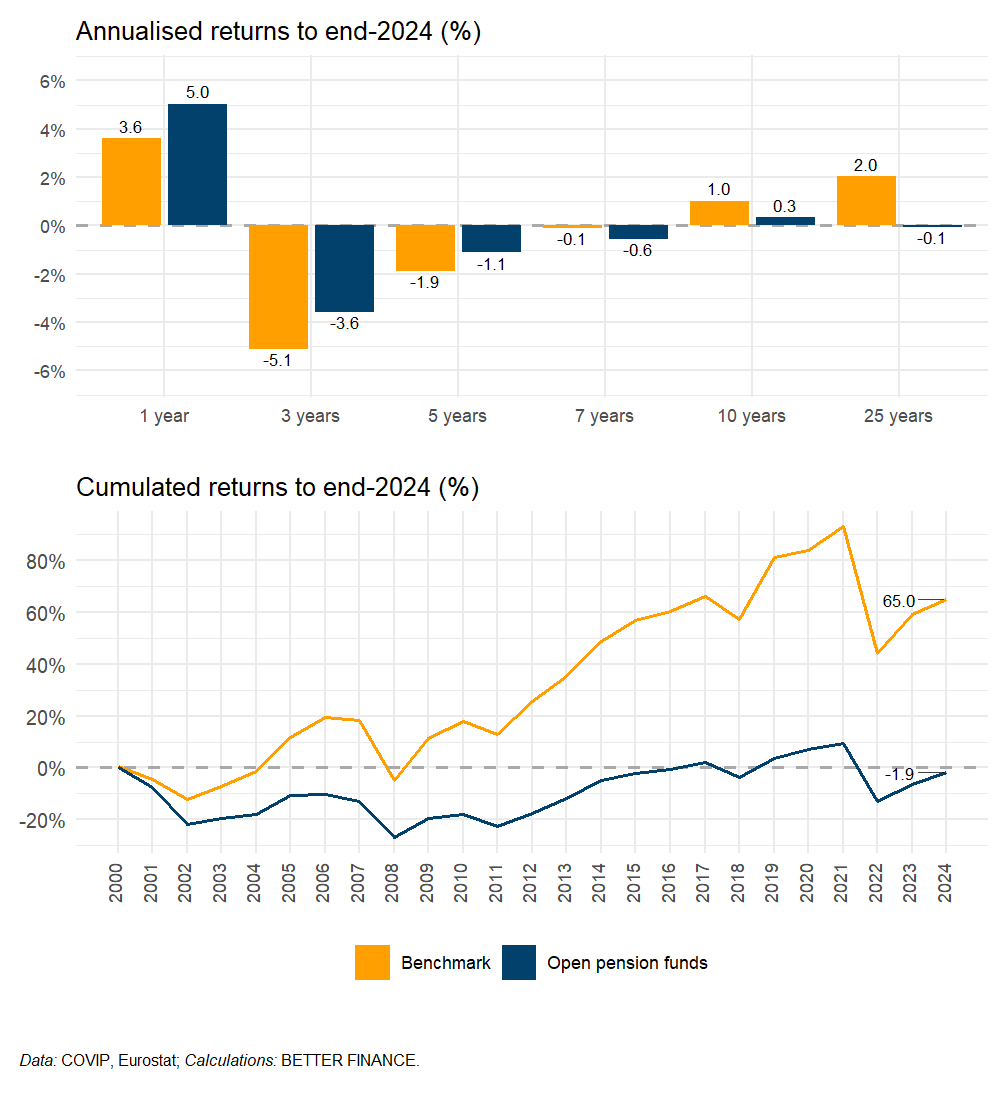

To compare the performance of Italian private pensions with that of European capital markets, we adapt the default benchmark portfolio presented in the introductory chapter of this report (se Section 3.2.4). We keep the pan-European equity and bond indices as underlying values, but adapt the weight of equity in the mix in line with the average asset allocation of each product category. The parameters are summarised in Table 12.6

| Equity index | Bonds index | Start year | Allocation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contractual pension funds | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2000 | 30%–70% |

| Open pension funds | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2000 | 41%–59% |

| PIP with profits | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2008 | 10%–90% |

| PIP unit-linked | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2008 | 55%–45% |

| Data: STOXX, Bloomberg; Note: Benchmark porfolios are rebalanced annually. | ||||

Admittedly, that makes the benchmark more difficult to beat for Open pension funds and PIPs unit-linked than for Contractual pension funds and PIPs with profits. Nevertheless, we believe that these asset allocations at least in part reflect external constraints on product managers’ investment decisions—starting with the risk aversion of sponsors and customers—and modulating the composition of the benchmark enables us to assess how they manage these constraints.

We then calculate the real net returns of the benchmark portfolios based on these parameters. Annualised and cumulated returns are calculated since 2000 for occupational and Open pension funds, since 2008 for PIP nuovi.

As Figure 12.20 show, neither Contractual nor Open pension funds manage to beat benchmark portfolio corresponding to their respective equity exposures. The annual average real return of the benchmark over 25 years is 1.1 p.p. superior to that of Contractual pension funds, and 2.1 p.p. superior to that of Open pension funds. In cumulated terms, this underperformance amounts to a 39.6 p.p. for the average Contractual fund investor, and 66.9 p.p. in Open funds.

We use two different benchmark compositions to assess the performance of the two variants of PIP nuovi in Figure 12.22 and Figure 12.23. The sluggish though consistent return of PIP with profits do not enable it to beat the extremely prudent 10% equity–90% bond benchmark portfolio, despite the significantly worse performance of the benchmark in 2022: Although falling close to the level of the with-profit PIPs that year, the performance of the benchmark portfolio remained superior, and started a recovery in 2023 (+7.8% in real terms), while the return of with-profit PIP stagnated (+0.8% in real terms, after charges).

The superior performance of PIP unit-linked equally pales when compared to a 65% equity–35% bonds benchmark portfolio. On average, PIP unit-linked fail to beat the annual average performance of the benchmark by 2 p.p.s and by 44 p.p.s in cumulated performnance since inception (17 years).

12.6 Conclusions

Italians may be right not to rely too much on their supplementary pensions. Considering the low real net returns shown in this chapter, it seems a priori reasonable to stay away from such paltry performance. Nevertheless, in Italy maybe more than in any other EU country, demographic pressures on the pay-as-you-go (PAYG) state pension in mounting fast and scaling up supplementary pensions is urgent. Staying away might not be an option; Italians need to engage with their supplementary pensions and question the drivers of their (under)performance.

Pension savers’ own risk aversion—and the incapacity of Italian supplementary pension providers to counter it—is sure to explain to a large extent the overly conservative asset allocation of occupational funds and the popularity of PIP with profits over their unit-linked counterpart. Reassuring sponsors and customers should, however, not lead to replace one risk with another: little equity exposure, as we have shown, means little volatility and saves investors the frights of the equity market roller-coaster, but it also means too little financial returns to preserve—let alone increase—the purchasing power of their savings.

Disaggregating the performance of Italian long-term and pension savings products by type of management—degrees of equity exposures—we have seen that the most “aggressive” of the gestioni offered to Italian pension savers do offer significantly higher returns than the average, even after deducting the often higher costs of management. That this equity-orientation remain the choice of only a minority of Italian investors bears testimony to the great need for more financial education and, crucially, more transparent, intelligible information for pension scheme participants regarding the costs and long-term performance.

Within the context of the ongoing policy discussion on the best design for pension systems, and, in particular, the revision of the rules governing supplementary pensions (see Section 4.4), Italy typically appears as a case where the introduction of automatic enrolment is premature—unless more detailed data on the performance of occupational funds reveal the existence of particular schemes with an outstanding performance track record—and where the introduction of a life-cycle approach could easily build on the existing offer of products to offer an optimal balance between the high long-term performance of gestione azionaria during the accumulation phase and the stability of returns from gestione obbligazionaria over the later years of working life and in retirement.

Acronyms

- AuM

- assets under management

- CBA

- collective bargaining agreement

- COVIP

- .na.character

- DB

- Defined benefits

- DC

- Defined contributions

- EU

- European Union

- GDP

- gross domestic product

- HICP

- harmonised index of consumer prices

- INPS

- Instituto Nazionale Previdenza Sociale

- ISC

- Indicatore Sintetico dei Costi

- NDC

- notional defined contribution

- PAYG

- pay-as-you-go

- PIP

- Piano Individuale Pensionistico

- RITA

- Rendita Integrativa Temporanea Anticipata

- TFR

- Trattamento di Fine Rapporto

- p.p.

- percentage point