Product categories

|

Reporting periods

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Pillar | Earliest data | Latest data |

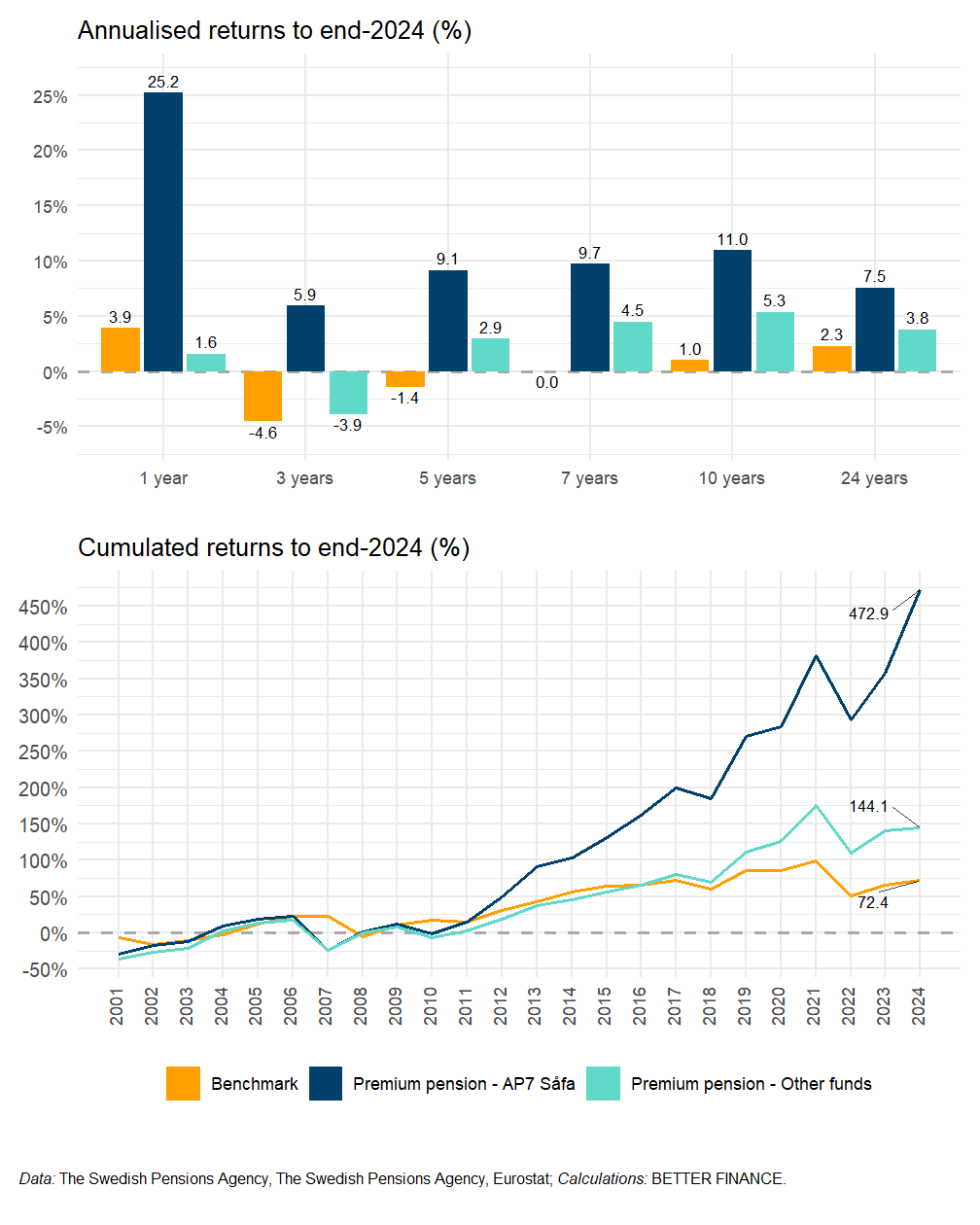

| Premium pension - AP7 Såfa | Public (I) | 2001 | 2024 |

| Premium pension - Other funds | Public (I) | 2001 | 2024 |

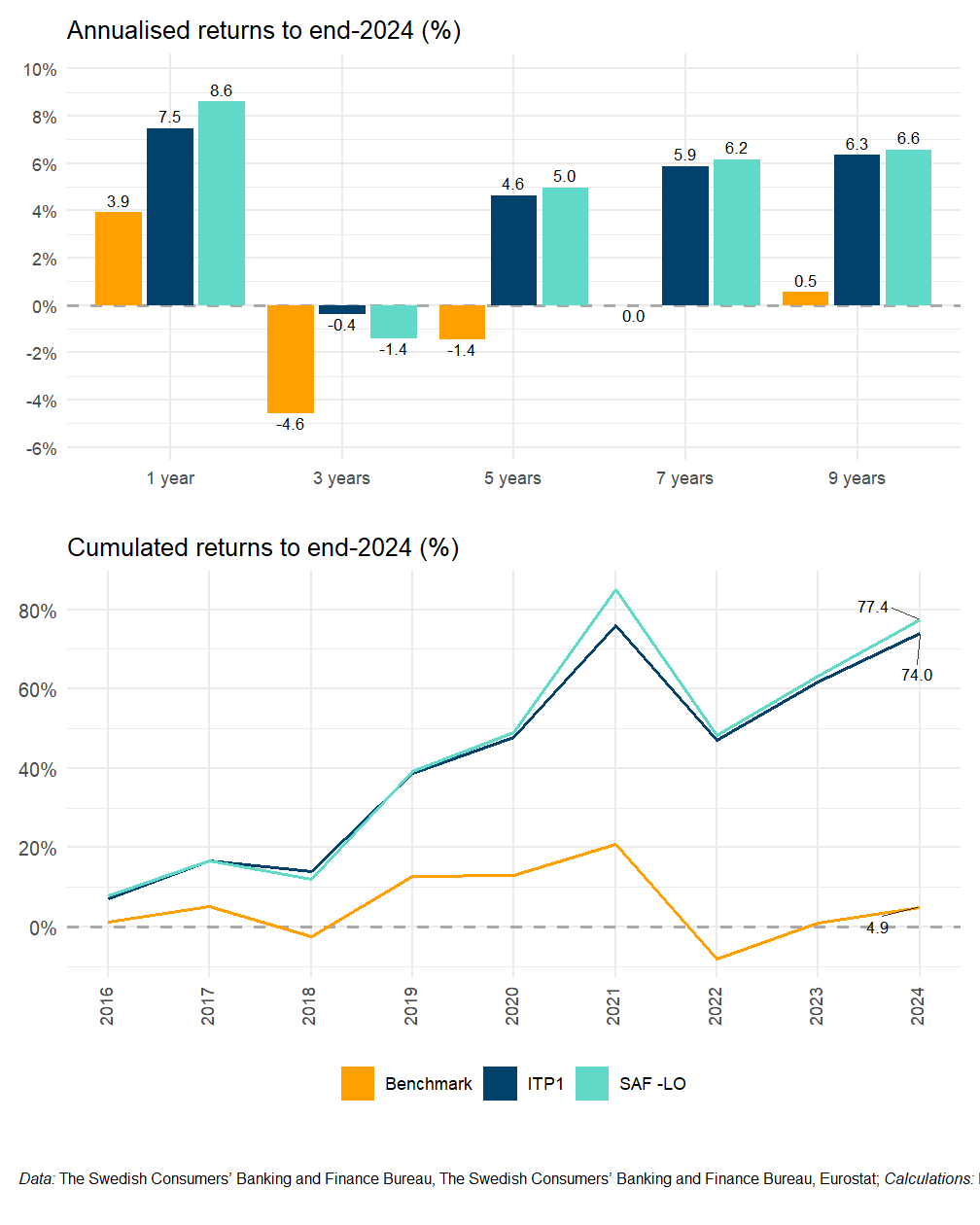

| ITP1 | Occupational (Pillar II) | 2016 | 2024 |

| SAF -LO | Occupational (Pillar II) | 2016 | 2024 |

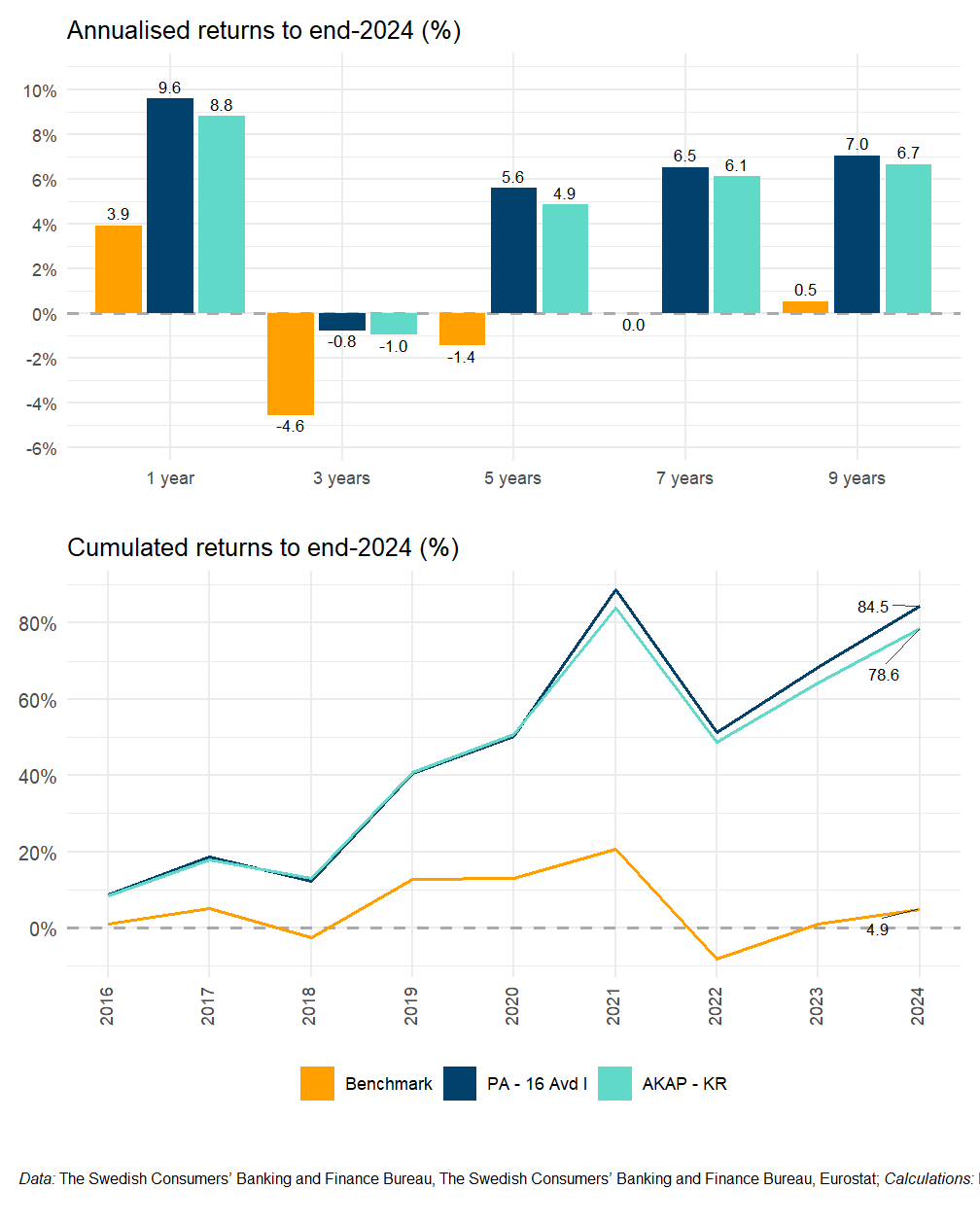

| PA - 16 Avd I | Occupational (Pillar II) | 2016 | 2024 |

| AKAP - KR | Occupational (Pillar II) | 2016 | 2024 |

Sammanfattning

Det svenska pensionssytemet består till stor del av avgiftsbestämda/fonderade pensioner. Totalt förvaltas över 8100 miljarder SEK (EUR 730 miljarder) i pensionskapital. I det allmänna pensionssystemet sätts 2.5% av lönen av till den så kallade premiepensionen. I premiepensionen har förvalsalternativet, AP7 Såfa, haft en genomsnittlig realavkastning på 6.8% sedan 2001, jämfört med 3.9% för alla andra valbara fonder. Tjänstepensionssystemet domineras av fyra stora avtal som täcker över 90% av alla arbetstagare. Tjänstepensionerna har till största del gått från att vara pay-as-you-go (PAYG) till fonderade pensionssystem.

Summary

The Swedish pension system contains a great variety of different retirement savings products with over SEK 8.1 trillion (EUR 730 billion) in assets under management (AuM). There are funded components in each of the three pillars. In the public pension system, 2.5% of earnings are allocated to the premium pension, whereas the default fund, AP7 Såfa, has had an average real rate of return of 6.8% compared to the 3.9% of all other funds over the last 22 years. The second pillar is dominated by four large agreement-based pension plans, covering more than 90% of the workforce. These have largely transitioned from a PAYG system to a funded system.

18.1 Introduction: The Swedish pension system

The Swedish pension system is a combination of mandatory and voluntary components. The system comprises three distinct pillars:

- Pillar 1 — The national pension

- Pillar 2 — Occupational pension plans

- Pillar 3 — Private pension

In 2022, the total pension capital was estimated at SEK 8,100 billion (EUR 730 billion), which corresponds to sixteen times the size of outgoing pension payments.1 The occupational pension system constitutes 48% of this capital. Within the first pillar, the fully funded segment of the public pension system, known as the premium pension, comprises 52% of the pension capital. In comparison, the remaining 48% is managed by the buffer funds. Table 18.1 shows an overview of the pension system in Sweden and offer valuable insights into the system’s diversity of retirement savings vehicles.

| Pillar I | Pillar II | Pillar III |

|---|---|---|

| State pension | Occupational pension | Voluntary pension |

| Mandatory | Mandatorya | Voluntary |

| PAYG/funded | Funded | Funded |

| DC/NDC | DC/DBb | DC |

| Flexible retirement age 63–69 | ERA of 55 or 63, usually paid out at 65 or 67 | Tax rebate abolished in 2016c |

| No earnings test | Normally a restriction on working hours | |

| Quick facts | ||

| Number of old-age pensioners: 2.3 millions | ||

| Coverage (active population): Universal | Coverage: >90% | Share contributing (2015): 24.2% |

| Pension plans: 4 major (agreement-based) | Funds: >30 | |

| Average monthly pension: EUR 1979 | Average monthly pension: EUR 568 | Average monthly pension: EUR 88.92 |

| Average monthly salary (gross, age 60-64): EUR 3100 | AuM: EUR 850 bln. | |

| Average replacement rate: 58%d | ||

|

[a] Occupational pension coverage is organized by the employer; [b] The defined benefit components are being phased out; [c] Tax rebate abolished in 2016; [d] OECD estimate 56%. |

||

The average pension in Sweden was EUR 1955 (SEK 21 694) per month before taxes in 2023; whereof EUR 1323 (SEK 14 632) came from the national pension, EUR 543 (SEK 6026) from occupational pensions and EUR 88 (SEK 985) derived from private pension savings. The outcome furthermore differed quite significantly between genders. For women, the average total pension was EUR 1672 (SEK 18 558) per month before taxes and for men EUR 2273 (SEK 25 211) per month before taxes.2 Although a lot of money is locked in the pension system in Sweden, the Swedish household’s savings rate is quite high.

In Sweden, there is no mandated retirement age, allowing individuals to personally determine both their retirement timing and the age at which they access their pension, either in part or in whole. However, individuals can claim their national pension from 63 onwards (raised from 62 in 2022). Additionally, there is no upper age limit for working, and everyone is entitled to work until the age of 69 (raised from 68 in 2022). As for occupational and private pensions, these can be withdrawn starting from the age of 65 onwards. The national pension in Sweden is administered by the Swedish Pensions Agency, which is responsible for managing the national pension and related pension benefits while providing crucial information to the public. The Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate safeguards that the operations of the Swedish Pensions Agency are executed in a manner that adheres to proper procedures and efficiency standards.

The Swedish national pension system underwent a significant transformation in 1999, marking a pivotal shift from a defined benefit system to a defined contribution system. In the pre-reform era, pensions were regarded as a social entitlement, guaranteeing individuals a specific percentage of their pre-retirement earnings. However, post-reform, pensions are primarily determined by the accumulated pension savings amassed during one’s active working years. This change aligns pensions with economic and financial developments, resulting in a more uncertain pension outcome, as retirees can no longer anticipate the exact amount of their pension. Consequently, there is a heightened need for comprehensive pension information in this new system. This shift has also influenced the occupational pension system, with most occupational pension plans adopting defined contribution structures or hybrids that combine defined contribution and defined benefit elements.3

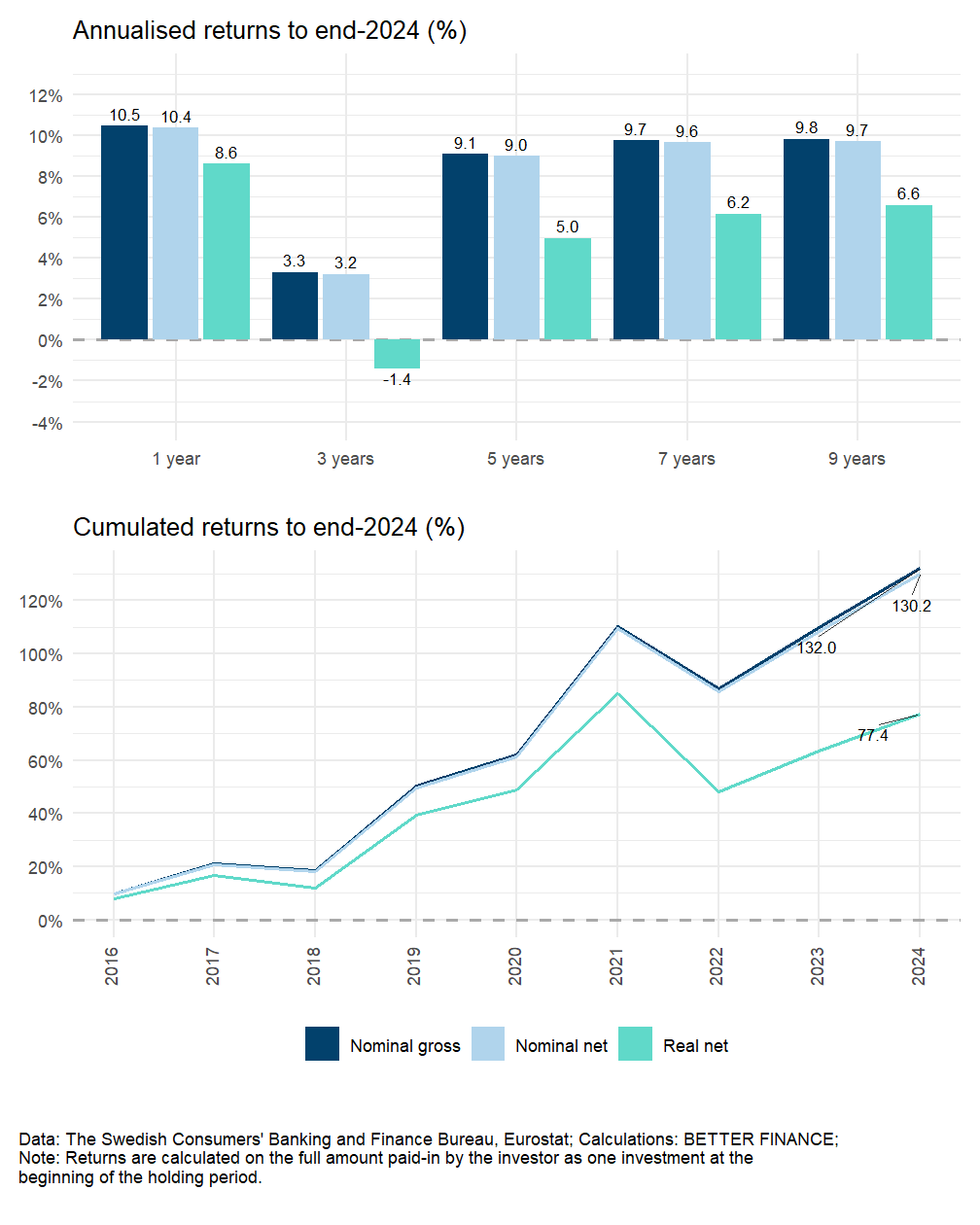

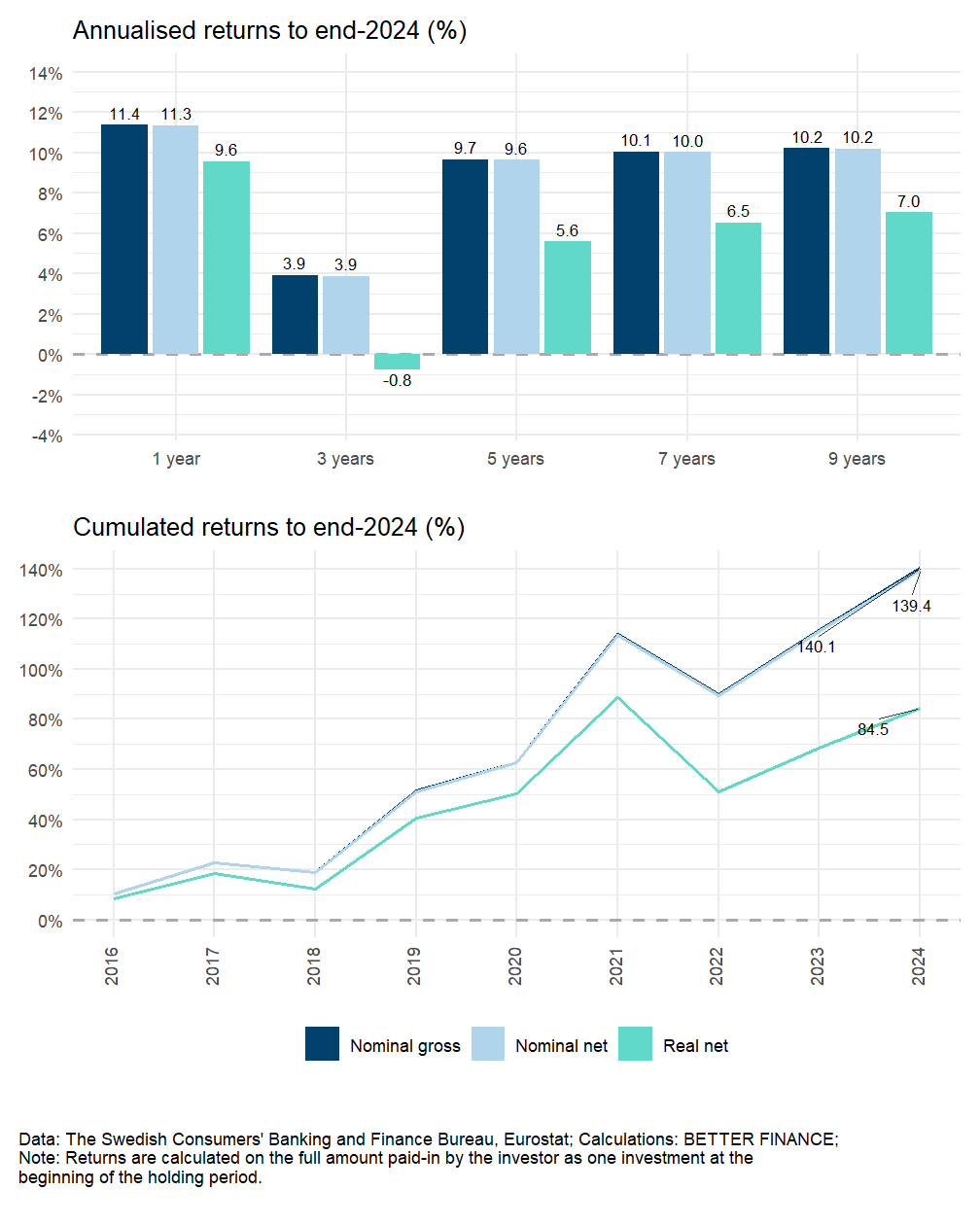

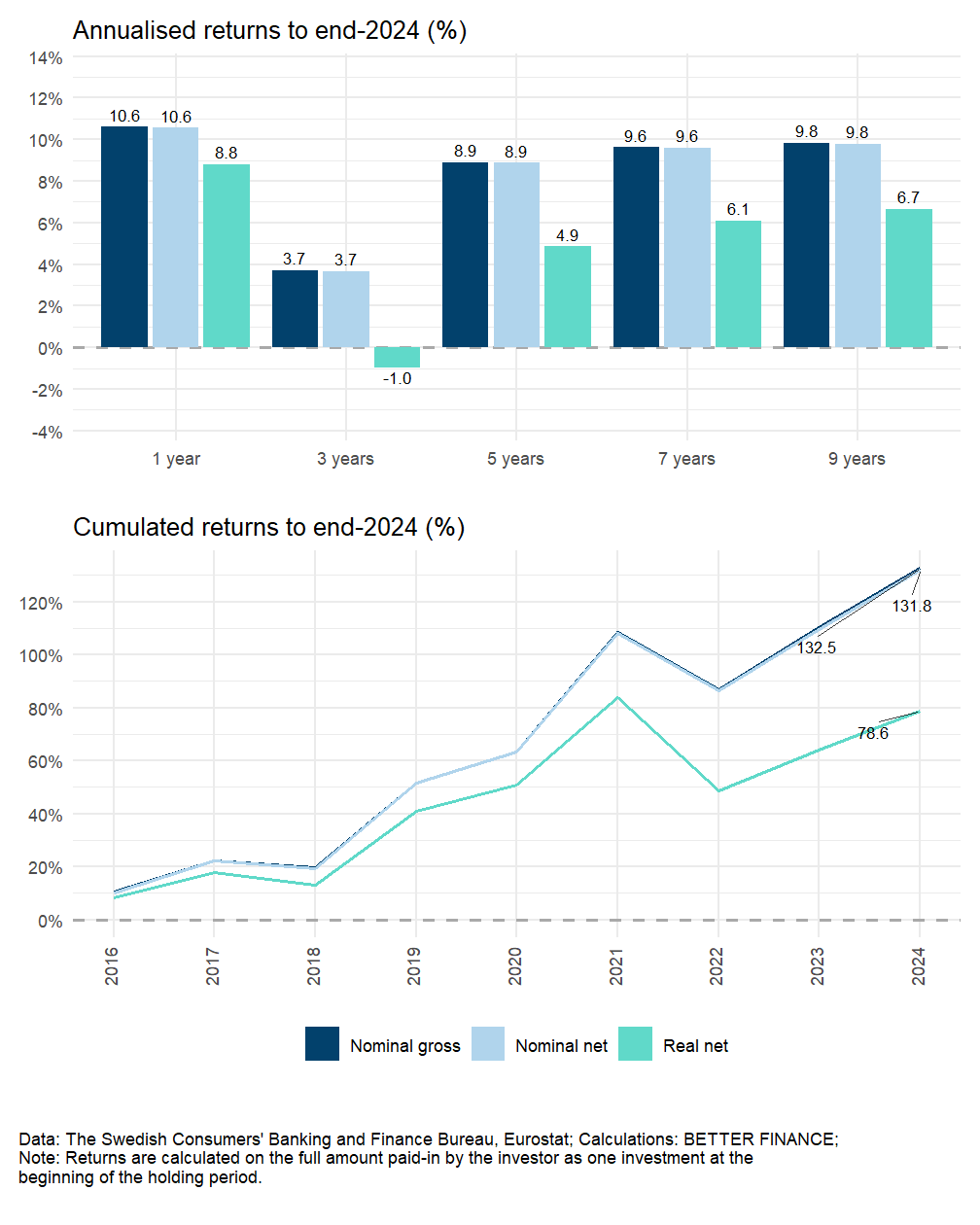

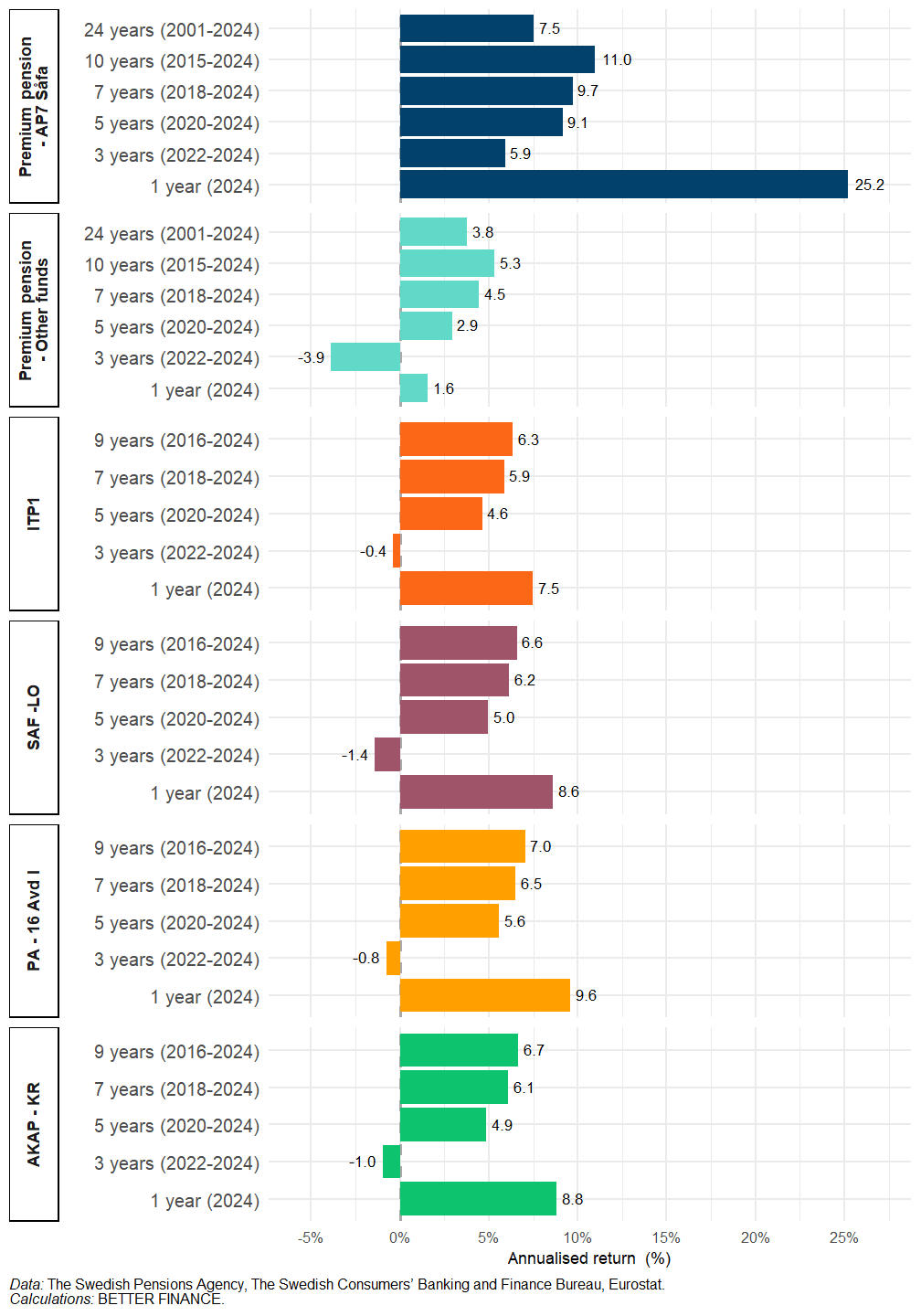

Table 18.2 offers an overview of the products examined in this report. These products span various pillars of the pension system and focus significantly on public and occupational options, which is good coverage of pension commitments. Table 18.3 presents the returns after charges and inflation (real net returns) of these products over varying holding periods.

Holding period

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | 7 years | Whole reporting period | 10 years | to... | |

| Premium pension - AP7 Såfa | 25.2% | 5.9% | 9.1% | 9.7% | 7.5% | 11.0% | end 2024 |

| Premium pension - Other funds | 1.6% | -3.9% | 2.9% | 4.5% | 3.8% | 5.3% | end 2024 |

| ITP1 | 7.5% | -0.4% | 4.6% | 5.9% | 6.3% | NA | end 2024 |

| SAF -LO | 8.6% | -1.4% | 5.0% | 6.2% | 6.6% | NA | end 2024 |

| PA - 16 Avd I | 9.6% | -0.8% | 5.6% | 6.5% | 7.0% | NA | end 2024 |

| AKAP - KR | 8.8% | -1.0% | 4.9% | 6.1% | 6.7% | NA | end 2024 |

| Data: The Swedish Pensions Agency, The Swedish Consumers’ Banking and Finance Bureau, Eurostat; Calculations: BETTER FINANCE | |||||||

18.2 Long-term and pension savings vehicles in Sweden

First pillar: The national pension

The national pension consists of an income-based pension, a premium pension and a guarantee pension. A share of 18.5% of the salary and other taxable benefits up to a maximum level of 8.07 income-base amount4 per year is set aside for the national retirement pension. A share of 16% is set-aside for the income pension, where the value of the pension follows earnings trends in Sweden. The income-based pension is financed on a PAYG basis, which means that pension contributions paid in are used to pay retirees the same year. The remaining 2.5% of the salary and other taxable benefits are set-aside for the premium pension, for which the capital is placed in funds. The individual can either choose what fund or funds to place their savings with or, if no choice is made, contributions will be made in the default alternative fund. This system is unique to Sweden and the first individual choices (allocations) were made in 2000. The aim was to achieve a spread of risk in the pension system by placing a part of the national pension on the capital market, enhance the return on capital and enable individual choices in the national pension system.5 The Swedish pensions Agency calculates that by 2030 the premium pension will constitute 20% of the total pension.

The capital for the income-based system is deposited in five buffer funds: the first, second, third, fourth and sixth national pension funds. The result of the income-based pension system is affected by several key economic and demographic factors. In the short-term, the development of employment is the most important factor, but the effect of the stock and bond markets is also of significance, particularly in case of major changes. In the long-term, demographic factors are most relevant.

Accumulated pension rights and current benefits in the income-based system grow with the increase in the level of earnings per capita. If the rate of growth of one salary would be slower than that of the average salary, for instance as a result of a fall in the size of the work force, total benefits would grow faster than the contributions financing them, which could induce financial instability. If the ratio of assets to liabilities in the income-based system falls below a certain threshold, the automatic balancing mechanism is activated and abandons the indexation by the level of average salaries.

In 2020, the parliament approved a new pension supplement in the national pension. The supplement will be paid out to pensioners with an income-based national pension of SEK 9200–17 400 (EUR 900–1700) and amounts to maximum SEK 600 per month. The purpose of the supplement is to increase the living standard for low-income workers during retirement. The supplement has been criticized for deviating from the so-called life-income principle and the fact that it is financed from the state budget (as opposed to the income pension which is financed from pension fees).

The third element of the national pension is the guarantee pension. It is a pension for those who have had little or no income from employment in their life. It is linked to the price base amount calculated annually by Statistics Sweden. The size of the guarantee pension depends on how long a person has lived in Sweden. Residents of Sweden qualify for a guaranteed pension from the age of 66. To receive a full guaranteed pension, an individual must in principle have resided in Sweden for 40 years after the age of 16. Residence in another European Union (EU)/European Economic Area (EEA) country is also credited toward a guaranteed pension. In addition to the national pension, pensioners with low pensions may be entitled to a housing supplement and maintenance support. In June 2022, the parliament passed a historically large increase of the minimum guarantee equal to SEK 1000. This implies that the maximum benefit for singles is raised from SEK 8779 to SEK 9781 and from 7853 to SEK 8855 for married individuals, i.e. increases of more than 10%.

There is an agreement in the Swedish Parliament to raise the different statutory retirement ages in the public pension system (Pillar I). First, the earliest eligibility age was raised from 61 to 62 in 2020 to 63 in 2023 and is expected to increase to 64 in 2026. Second, the eligibility age for the minimum guarantee has been raised from 65 in 2022 to 66 in 2023 and is then expected to increase to 67 in 2026. Those who have worked for 44 years or longer will be exempt from these changes. Third, the mandatory retirement age was raised from 67 to 68 in 2020 and then to 69 in 2023. A plan is also to index these retirement ages to a so-called “target age”. The target age will be based on remaining life expectancy, although the details are yet to be laid out.

For administering the income-based pension system, a fee is deducted annually from pension balances by multiplying these balances by an administrative cost factor. In 2023, the fee amounted to 0.03%.6 The deduction is made only until the insured begins to withdraw a pension. At the current level of cost, the deduction will decrease the income-based pension by approximately 1% compared to what it would have been without the deduction.

The premium pension system is a funded system for which the pension savers themselves choose the funds in which to invest their premium pension savings. The premium pension can be withdrawn, in whole or in part, from the age of 63 (62 in 2022). The pension is paid out from selling off the accumulated capital. The individual choice in the premium pension system furthermore results in a spread on return on the pension capital depending on the choice of fund or funds. Figure 18.1 shows the accumulated savings in the premium pension.

The choices made by individuals within the premium pension system can significantly impact the returns on their pension capital, as it depends on their chosen fund or funds. The premium pension system has faced criticism due to the abundance of available funds and the wide variation in pension outcomes. In response to these concerns, the government announced in December 2017 that it would implement changes proposed by the Pensions Agency to improve the quality and oversight of participating companies.7 These new regulations went into effect on , and include requirements such as fund companies managing a minimum of SEK 500 million outside the Premium Pension, having a three-year operating history, acting in the best interests of retirement savers, meeting minimum sustainability criteria, and establishing one contract per fund with the Pensions Agency instead of one contract per company.8

Under the new regulations, companies seeking participation in the Premium Pension system were required to (re)submit applications to the Pensions Agency. In early 2019, 70 companies submitted applications, which covered 553 funds, representing a decrease from the prior count of over 800 funds recorded by the end of 2018. The primary objective of these new rules is to prevent the involvement of unscrupulous and fraudulent companies in the system. Concerns about such fraudulent practices were raised following incidents involving fund companies like Falcon Funds, Fondeum and Global Financial Group (GFG) in 2016, Allra and Advisor in 2017, and Solidar in 2018.

In efforts to reform the premium pension, the Swedish government, through the parliament decision, established a new independent agency called the Swedish Fund Selection Agency in 2022, tasked with selecting investment funds available within the premium pension system.9 This initiative aims to provide savers with a choice of funds managed by reputable and high-quality fund managers who adhere to stringent sustainability standards. The selected funds will undergo periodic evaluations, and those that fail to meet the specified quality standards may be replaced. The primary objective is to ensure that the chosen funds yield favourable investment returns, ultimately securing higher pensions for savers. Additionally, this approach is expected to attract and retain top fund managers at a cost-effective rate. Some actors, including the Swedish Investment Fund Association, argue that the proposed changes may lead to lower pensions, decrease competition among fund providers an limit the freedom of choice for individual investors.10 For now, all applicants who have met the criteria have been permitted to offer investment funds on the platform, where, as of March 2023, there were 478 eligible funds registered in the Premium Pension.

Second pillar: Occupational pensions

The Swedish occupational pension system is primarily governed by collective agreements. While Swedish companies are not legally obligated to provide pensions to their employees, the presence of a collective agreement at the workplace necessitates the establishment of an occupational pension plan. This system extends coverage to more than 90% of the workforce. It’s important to note that self-employed individuals are not included in occupational pension plans, and this primarily affects smaller companies in emerging business sectors that lack collective agreements.11

There are four primary collective agreements corresponding to different sectors, each with its dedicated pension plan. These four agreements encompass a significant membership base: the SAF-LO Collective Pension, tailored for blue-collar workers with 2.8 million members; the Supplementary Pension Scheme for Salaried Employees in Industry and Commerce (ITP), designed for white-collar employees, boasting 2 million members; the Collectively Negotiated Local Government Pension Scheme (KAP-KL), with 1 million members; and the Government Sector Collective Agreement on Pensions (PA-03/PA-16), which counts 500 000 members among its participants.12

In each of the four collectively negotiated pension schemes, employees can select a fund manager for a portion of their pension. To maximize the occupational pension for employees, a dedicated “choice centre” exists for each collective pension plan. The role of these “choice centre” is to secure reputable managers for employees’ occupational pensions. Employees can make choices between various forms of traditional insurance and/or unit-linked insurance. The extent of this individual portion depends on factors such as the employer’s annual pension provision contributions, the duration of these contributions, and the investment management strategies employed. In the case of two of the collective pension schemes, KAP-KL and SAF-LO, employees can opt to choose a fund manager for the entire pension amount. However, if an individual does not select, their pension capital will be automatically placed in the default alternative. Across all four agreements, this default option consists of traditional insurance from the choice centre affiliated with the occupational pension plan.

Where no collective agreement is in place at the workplace, a company can establish an individual occupational pension plan for its employees. Among those companies operating without a collective agreement, some opt for such an occupational pension plan, while others choose not to provide any pension benefits to their employees. These individual pension plans can differ in their structure and benefits. Nevertheless, a common feature is that they often offer less favourable terms and entail higher costs when compared to collectively negotiated pension schemes.

In 2017, the Ministry of Finance proposed measures to simplify and reduce the cost of transferring occupational pension funds between providers.13 Currently, the ability to transfer pension capital is generally limited to funds accrued after 2007 that have yet to be paid out, with associated fees, particularly in individual occupational pension plans. Critics argue that this restricts competition, reduces retirement savings returns, and creates lock-in effects.

In April 2019, the government presented a report advocating lower transfer fees and a specified maximum fee in Swedish Kronor (SEK).14 The parliament approved these recommendations in November 2019 and urged further exploration. In March 2020, the Ministry of Finance suggested a maximum fee of 0.0127 times the price base amount (600 SEK or EUR 59.8 for 2020).15 These new regulations came into effect in April 2021. In May 2022, it was decided that the portability right should also apply to pension capital accumulated before 2007.

In December 2016, Sweden adopted the IORP II Directive, aimed at ensuring the financial stability of occupational pensions and enhancing member protection through stricter capital solvency requirements. This directive also clarifies the legal framework for occupational pension businesses. However, critics contend that these rules create competitive imbalances, as they only affect companies exclusively offering occupational pension insurance, not those providing other insurance services. In November 2019, the government supplemented the EU Directive with additional national legislation.16

ITP

The ITP agreement consists of two parts: defined contribution pension ITP 1 and defined benefit pension ITP 2. Employees born in 1979 or later are covered by the defined contribution pension ITP 1. In ITP 1 the employer makes contributions of 4.5% of the salary per year, up to a maximum of 7.5 income base amounts. If the salary exceeds this level, the amount of the contribution is also 30% of the salary above 7.5-income base amount. There is also an additional contribution that the employer organizations can choose to include, the so-called partial pension contribution. This contribution currently varies between 0.2% – 1.5%.

Half of the ITP 1 pension must be invested in traditional pension insurance, but the individual can choose how to invest the remaining half. It can be placed in traditional insurance and/or unit-linked insurance. The premiums of those who do not specify a choice are invested in traditional pension insurance with Alecta. The eligible insurance companies for traditional insurance are Alecta, AMF, Folksam, Skandia and SEB and for unit-linked insurance they are Futur Pension (previously Danica pension), SPP, Handelsbanken, Movestic and Swedbank.

SAF-LO

The SAF-LO occupational pension plan is a defined contribution plan by definition. The terms of the plan were improved in 2007, mostly in response to perceived unfairness in the terms of the pension provisions for blue-collar and white-collar workers. Like for ITP 1 the employer now makes contributions of 4.5 percent of the salary, up to a maximum of 7,5 income base amounts. If the salary exceeds this level, the amount of the contribution is also 30 percent. SAF-LO also contains a partial pension contribution that the employer can choose to add. The additional contribution is currently ranging between 0.7. and 1.7 percent.

The individual can choose how to invest the pension capital and it can be placed in traditional insurance and/or unit-linked insurance. The eligible insurance companies for traditional insurance are Alecta, AMF, Folksam and SEB and for unit-linked insurance they are AMF, Futur Pension, Folksam, Handelsbanken, Länsförsäkringar, Movestic, Nordea, SEB, SPP and Swedbank.

PA 03

The pension plan for central government employees, PA 16 — Avd II (formerly PA 03), is a hybrid of defined contribution and defined benefit. The defined contribution component in PA 03 consists of two parts: individual old age pension and supplementary old age pension. The total premium amounts to 4.5% of the pensionable income up to a ceiling of 30 income base amounts. Of the total premium, 2.5% and 2% is allocated to the individual pension and the supplementary pension respectively. The individual can choose how the contribution of the individual retirement pension should be placed and managed. Contributions to the supplementary pension cannot be invested by the employee and are instead automatically invested in a traditional low-risk pension insurance fund.

The defined-benefit pension applies to those who earn more than 7.5 income base amounts. If the individual earns between 7.5 and 20 income-base amounts, the defined-benefit pension comprises 60% of the pensionable salary on the component of pay that exceeds 7.5 income base amounts. If the individual earns between 20 and 30 income-base amounts, the defined-benefit pension comprises 30% of the pensionable salary on the component of pay that exceeds 20 income base amounts. There is also a defined benefit pension on income less than 7.5 income base amounts in accordance with transitional provisions due to the implementation of PA 16 — Avd I (see below).

In 2016, a new pension plan, PA 16 — Avd I, for central government employees was implemented. PA 16 covers those born in 1988 or later. Just like PA 16 — Avd II, PA 16 — Avd I has two defined contribution components. The individual pension (2.5% of income up to 7.5 income base amounts) can be invested by the employee, whereas the supplementary pension (2% of income up to 7.5 income base amounts) is invested in a low-risk pension insurance fund. The contribution for earnings above the ceiling amounts to 20% and 10%, respectively. PA 16 also contains a mandatory partial pension contribution amounting to 1.5%. These contributions are invested in a low-risk pension insurance fund. The eligible insurance companies providing individual retirement pension in the shape of traditional insurance are Alecta, AMF, Kåpan, and as unit-linked insurance they are AMF, Futur Pension, Handelsbanken, Länsförsäkringar, SEB and Swedbank.

KAP-KL

The KAP-KL agreement consists of two parts: the defined contribution pension AKAP-KL and defined benefit pension KAP-KL. Employees born in 1986 or later are covered by the defined contribution pension AKAP-KL. In AKAP-KL, the employer pays in an amount of 4.5% of the salary towards the occupational pension. If the salary exceeds 7.5 income base amounts, the amount is increasing with 30% of the salary that exceeds 7.5 income base amounts up to a maximum of 30 income base amounts. Employees covered by KAP-KL get 4.5% of the salary contributed to their occupational pension. For a salary over 30 income base amounts, no premium is paid. Instead, there is a defined benefit old age pension that guarantees a pension equivalent to a certain percentage of the final salary at the age of retirement. A new agreement for local government employees, AKAP-KR, was passed in December 2021 and will be phased in from 2023. The new agreement comes with raised contribution rates; 6% and 31.5% for earnings below and above 7.5 income base amounts, respectively. The individual can choose how to invest the pension capital and it can be placed in traditional insurance and/or unit-linked insurance. The eligible insurance companies for traditional insurance in AKAP-KL are Alecta, AMF, KPA and Skandia and for the unit-linked insurance in AKAP-KL they are AMF, Futur Pension, Folksam, Handelsbanken, KPA, Länsförsäkringar, Lärarfonder, Nordea, SEB and Swedbank.

Third pillar: Private pensions

Private pension saving is voluntary, but it is subsidized via tax deductions. In 2014, 34.5% of those aged 20 to 64 made contributions to a private pension account. The tax deduction for private pension savings is only profitable for high-income earners.

Private pension savings can be placed in an individual pension savings account (IPS) or in private pension insurance. Money placed in an IPS and in private pension insurance is locked until the age of 55. After that the individual can choose over how many years the pension should be paid out. The minimum payout is 5 years in both IPS and private pension insurance. However, only money in private pension insurance can be paid out for life (annuity).

Unlike the national pension plan and the occupational pension plans, private pension plans are individual. This results in less transparency both when it comes to offered products within the private pension plans and the charges on these products. The deduction for private pension savings has been reduced over the years. From January 1st, 2015 it was reduced from EUR 1195 to EUR 179 (SEK 12 000 to SEK 1800) per year, equivalent to EUR 15 (SEK 150) in monthly savings. On (MISSING DATE), the deduction was abolished. The motive for this is that the deduction favours high-income earners. In 2015, the share of private pension savers dropped to 24.2%. Those who still contribute to private pension accounts are thus subject to double taxation.

Several actors in the pension industry advocate the need for new incentives for people to save privately for retirement. One suggestion is that the government match private contributions, like what is already in place in Germany, matching benefits for low- and medium-income earners as opposed to tax subsidies which tend to favour the rich. The problem is of course that the government must bear the costs of matching in the future when the contributors retire. In addition, the redistributional outcome of government-subsidized savings may be different than the intended if low- and medium-income earners are less likely to contribute. The effect on total savings may also be limited if there are substitution effects across different saving forms.

With the abolishment of tax-deductible pension accounts, retirement savers need to find new ways to save for retirement that are not directly related to the pension. The most popular savings vehicle today is called Investeringssparkontot (ISK), an investment and savings account that was introduced in January 2012. The purpose of the new account is to make it easier to trade in financial instruments. Unlike an ordinary securities account, there is no capital gains tax on the transactions. Capital gains tax has been replaced by an annual standardised tax (more on this in the Taxation section).

After the lowering of the deduction for private pension savings, ISK is now regarded as a low tax alternative to private pension savings. ISK has enjoyed widespread popularity and the number of ISK accounts has increased dramatically. In 2019, the number of unique account holders exceeded 2.6 million. In 2023 ISK funds accounted for 9% of the households’ total fund assets as compared to 23% for private pension insurance. The relative importance of ISK is however likely to increase in the future; 22% of net savings in funds in 2023 was allocated to ISK accounts.

| Fund type |

Fund assets

|

Net saving (%) | Share of assets (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEK mln. | EUR mln. | |||

| Direct fund investments | 537 167 | 46 877 | -9.1% | 6.7% |

| ISK | 708 396 | 61 820 | 21.8% | 8.9% |

| IPS | 171 181 | 14 939 | -3.2% | 2.2% |

| Private pension insurance | 1 842 739 | 160 812 | 24.6% | 23.2% |

| Premium Pension (1st pillar) | 2 540 328 | 221 688 | -14.3% | 31.9% |

| Trustee-registered funds | 933 778 | 81 489 | 42.5% | 11.7% |

| NGOs | 146 321 | 12 769 | 0.6% | 1.8% |

| Swedish companies | 908 015 | 79 240 | 25.2% | 11.4% |

| Others | 170 490 | 14 878 | 11.9% | 2.1% |

| Total | 7 958 415 | 694 512 | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Data: Fondbolagen.se. | ||||

The costs associated with the administration and management of the funds affect the size of outgoing pension payments. To reduce the costs in the premium pension system, the capital managers associated with the premium pension system are obliged to grant a rebate on the ordinary management fee of the funds. In 2021, the rebates to pension savers were equivalent to a discount in fund management fees of about 0.35 percentage points. The rebates on the ordinary management fees in the premium pension system are of great importance; without them pensions would be approximately 11% lower. Furthermore, the pension savers are in a position to influence the costs of their premium pensions by choosing funds with lower management fees. The net charges (after rebates) in the premium pension system are reported in the upper part of Table 18.5.17

18.3 Charges

Charges of Pillar I

The costs associated with the administration and management of the funds affect the size of outgoing pension payments. To reduce the costs in the premium pension system, the capital managers associated with the premium pension system are obliged to grant a rebate on the ordinary management fee of the funds. In 2021, the rebates to pension savers were equivalent to a discount in fund management fees of about 0.35 percentage points. The rebates on the ordinary management fees in the premium pension system are of great importance; without them pensions would be approximately 11% lower. Furthermore, the pension savers are in a position to influence the costs of their premium pensions by choosing funds with lower management fees. The net charges (after rebates) in the premium pension system are reported in upper part of Table 18.5.18

The costs in the income pension are shown in the lower part of Table 18.5. Management fees in the income pension cover the costs of the buffer funds. The capital managed by the buffer funds marginally exceed the capital managed in the premium pension (SEK 1826 billion in 2022). However, returns to scale in the buffer funds imply lower costs than in the premium pension.

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premium pension | 0.36% | 0.33% | 0.30% | 0.28% | 0.27% | 0.25% | 0.23% | 0.20% | 0.15% | 0.14% | 0.15% | 0.14% |

| Administrative fee | 0.10% | 0.09% | 0.07% | 0.07% | 0.06% | 0.07% | 0.04% | 0.04% | 0.04% | 0.03% | 0.02% | 0.03% |

| Income pension | 0.20% | 0.20% | 0.21% | 0.19% | 0.18% | 0.16% | 0.16% | 0.15% | 0.13% | 0.11% | 0.10% | 0.10% |

| Administrative fee | 0.03% | 0.03% | 0.03% | 0.03% | 0.03% | 0.03% | 0.03% | 0.03% | 0.03% | 0.03% | 0.03% | 0.03% |

| Data: Orange report. | ||||||||||||

To meet the new need of information in the new pension system, the orange envelope was introduced in 1999. It contains information about contributions paid, an account statement, a fund report for the funded part and a forecast of the future pension. The purpose of the orange envelope is to get more people interested in their pension and get more attention with the help of the special design, the orange colour and a concentrated distribution once a year. The orange envelope has now become a brand, a trademark for pensions. Banks and insurance companies use it in their sales campaign and in media the orange envelope is used to illustrate pensions.

Pillar II

Legislation from 2007 implies that individuals can choose which company should manage their occupational pension capital. The so-called portability right accrues to capital earned after July 1st, 2007. Capital earned before this date can be moved if the default managing company itself has agreed to give their investors this right. It is estimated that around 44 percent of the occupational pension capital today is covered by the portability right.19 Thus, the share of pension capital that can be moved will increase over time, which will further strengthen the competition and keep the fees low. As discussed in the background section, there are also policy proposals to extend the portability rights and reducing the associated moving costs. In May 2022, the parliament decided to extend the portability rights also to pension capital accumulated before 2007.

The selectable companies within each pension plan are included through a procurement procedure which, especially in the last years, have kept the fees down. The disclosure of charges in the occupational pension system is quite good, although it can be difficult for the average citizen to understand the information that is available. In the occupational pension system, there is typically a yearly fixed fee and a percentage fee on the capital (i.e. management fee). The fixed fee is usually low and covers administrative costs of the pension company.

| Fund type | Name | Fixed costs (SEK) | Management fees (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITP 1 | |||

| Traditional insurance | Alecta (default) | 0 | 0.05 |

| Traditional insurance | AMF | 40 | 0.15 |

| Traditional insurance | Folksam | 0 | 0.12 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Handelsbanken | 0 | 0.07 - 0.13 |

| Unit-linked insurance | SPP | 0 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Swedbank | 0 | 0 |

| SAF LO | |||

| Traditional insurance | Alecta | 50 | 0.15 |

| Traditional insurance | AMF | 40 | 0.1 |

| Traditional insurance | Folksam | 50 | 0.15 |

| Traditional insurance | AMF (default) | 50 | 0 |

| Traditional insurance | SEB | 50 | 0.09 |

| Unit-linked insurance | AMF | 50 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Folksam LO | 0 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Futur Pension | 0 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Handelsbanken | 0 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Länsförsäkringar | 40 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Movestic | 50 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Nordea | 45 | 0.18 - 0.22 |

| Unit-linked insurance | SEB | 45 | 0.1 - 0.25 |

| Unit-linked insurance | SPP | 0 | 0.15 - 0.25 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Swedbank | 0 | 0.21 - 0.25 |

| PA 03 & PA 16 | |||

| Traditional insurance | Alecta | 75 | 0.15 |

| Traditional insurance | AMF | 75 | 0.15 |

| Traditional insurance | Kåpan Pensioner (default) | 0 | 0.05 |

| Unit-linked insurance | AMF | 75 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Futur Pension | 65 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Handelsbanken | 75 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Länsförsäkringar | 75 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | SEB | 75 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Swedbank | 75 | 0 |

| AKAP-KR | |||

| Traditional insurance | Alecta | 65 | 0.15 |

| Traditional insurance | AMF | 65 | 0.15 |

| Traditional insurance | KPA (default) | 48 | 0.05 |

| Traditional insurance | Skandia | 65 | 0.16 |

| Unit-linked insurance | AMF | 65 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Folksam LO | 65 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Futur Pension | 65 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Handelsbanken | 65 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | KPA Pension | 65 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Länsförsäkringar | 65 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Lärarfonder | 65 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Nordea | 65 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | SEB | 65 | 0 |

| Unit-linked insurance | Swedbank | 65 | 0 |

| Data: Konsumenternas (The Swedish Consumers’ Banking and Finance Bureau). | |||

Pillar III

For the private pension system, however, it is difficult to get a good overview of the available pension products and hence the charges on these products. There are two tax-favoured (pre-2016) private pension vehicles: IPS and private pension insurance. The majority of pension providers of IPS and private pension insurance charge a fixed fee. These typically range between EUR 10 and EUR 40 per year and are hence higher than in the occupational pension system. In IPS, only two out of eleven providers charge a management fee. Instead, the individual is subject to fund fees which vary substantially by fund type and pension provider. It is also relatively expensive to move the IPS capital to another company. This fee typically amounts to EUR 50, which in relation to the invested capital can be sizeable.

In private pension insurance accounts, the fee structure depends on whether the capital is unit-linked or traditional. Traditional insurance only imposes a management fee whereas unit-linked insurance both contains management and fund fees. In some cases, investors also pay a deposit fee of 1% - 2%. The savings invested in these products will decrease since the deduction for private pension savings was abolished in January 2016.

In many private pension products (including individual occupational pension plans), there is a cost to move the capital to another company (not reported here). These fees typically range between 0%-3%, reaching 0% after a specific number of years of investment. These fees have been criticized for causing serious lock-in effects. For many it is simply not worth moving the capital, despite high management fees.

18.4 Taxation

Taxation during the accumulation phase looks different in the different pillars. In the public pension, individual contributions are deductible from the tax base and there is no tax on returns. Employers can partially deduct contributions to the second pillar.20 When it comes to private pension savings, there was a tax deduction of SEK 1800 (EUR 179) per year available, but it was abolished in January 2016. There is no tax on returns in the first pillar. In contrast, returns in the occupational pension system and in the private pension vehicles are subject to an annual standard rate tax based on the value of the account and the government-borrowing rate. Specifically, the value of the account on January 1st multiplied by the government borrowing-rate gives the standard earnings which are then subject to a 15% tax rate.

| Product categories |

Phase

|

Fiscal Regime | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contributions | Investment returns | Payouts | ||

| Premium pension - AP7 Såfa | Exempted | Exempted | Taxed | EET |

| Premium pension - Other funds | Exempted | Exempted | Taxed | EET |

| ITP1 | Exempted | Taxed | Taxed | ETT |

| SAF -LO | Exempted | Taxed | Taxed | ETT |

| PA - 16 Avd I | Exempted | Taxed | Taxed | ETT |

| AKAP - KR | Exempted | Taxed | Taxed | ETT |

| Source: BETTER FINANCE own elaboration, based on The Swedish Pensions Agency. | ||||

| Source: BETTER FINANCE own elaboration, based on The Swedish Consumers’ Banking and Finance Bureau. | ||||

During the decumulation phase, all pension income in Sweden is taxed as earned income. The rate varies depending on the size of the pension payment due to the progressive income taxation in Sweden. The Swedish income tax is even higher for pensioners than workers because of the earned income tax credit.21 The Swedish tax system works as follows. A proportional local tax rate applies to all earned income, including pension income. Furthermore, for income above a certain threshold, the taxpayer also has to pay central government income tax. The marginal tax rate is 20% for incomes above EUR 50 756 (SEK 509 300) and 25% for incomes there-above.22

From a phase taxation point of view as shown in Table 18.7, Pillar I can be described as Exempt Exempt Taxed (EET) and Pillars II and III Exempt Taxed Taxed (ETT).

ISK

On ISK there is an annual standard rate tax, based on the value of the account as well as the government-borrowing rate. The financial institutions report the standard rate earnings to the tax authorities and there is no need to declare any profit or loss made within the account.

The calculation of the standard rate earnings is based on the average value of the account as well as the government-borrowing rate. The average value of the account is calculated by the account value of the first day of each quarter added together, divided by four, and the sum of all deposits during the year divided by four. The average value of the account multiplied with the government borrowing rate as of 30 November the previous year, plus 1 percentage point (0.75 percentage points before January 1st, 2018), gives the standard earnings. The standard earnings cannot fall below 1.25%, however. The standard earnings are reported to the tax authority by the financial institutions. The standard earnings are taxed at 30%.

In 2021, the government borrowing rate was 0.23%, which means that the calculated average value of an account is taxed with 0.375% (\(0.3 \times 0.0125 = 0.00375\)).

In contrast to individual pension savings accounts, the investment and savings accounts are free from management fees. The taxation of the accounts is very favourable, and the Swedish Pensions Agency considers the investment and savings account a great alternative to the individual pension savings account. There is no binding period, and withdrawals can be made free of charge at any given time. The taxation of the account is more favourable during periods with low borrowing rates, as the standard rate earnings are based partially on the government-borrowing rate. The taxation is also more favourable during periods of stock market rise than stock market decline, compared to saving vehicles with standard capital gains taxation.

Since ISK was introduced in 2012, the economy has been characterized by low interest rates and a positive stock market development. This, in combination with the abolishment of the deduction for private pension savings, has contributed to the rapid spread of ISK accounts. Some argue that ISK will replace the old tax-favoured private pension savings accounts. However, critics argue that ISK is more of a regular savings vehicle; ISK capital cannot be withdrawn as a life annuity, and it does not mandate the account holder to save long-term.

18.5 Performance of Swedish long-term and pension savings

Real net returns of Swedish long-term and pension savings

This section reports on returns on pension capital in the first and second pillars. There are no readily available data on returns in the private pension system (Pillar III) — one would have to turn to the homepage of each pension provider for this information.

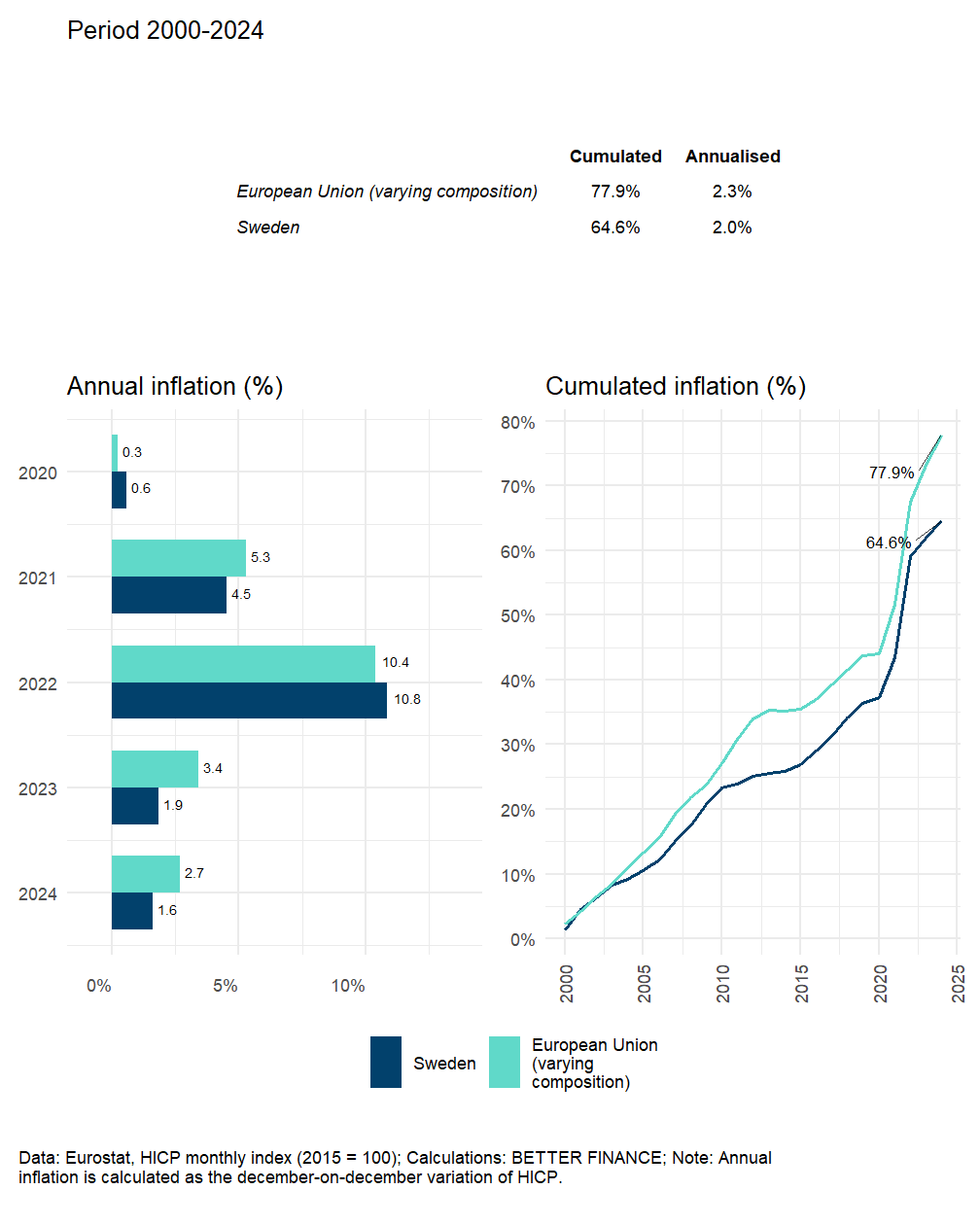

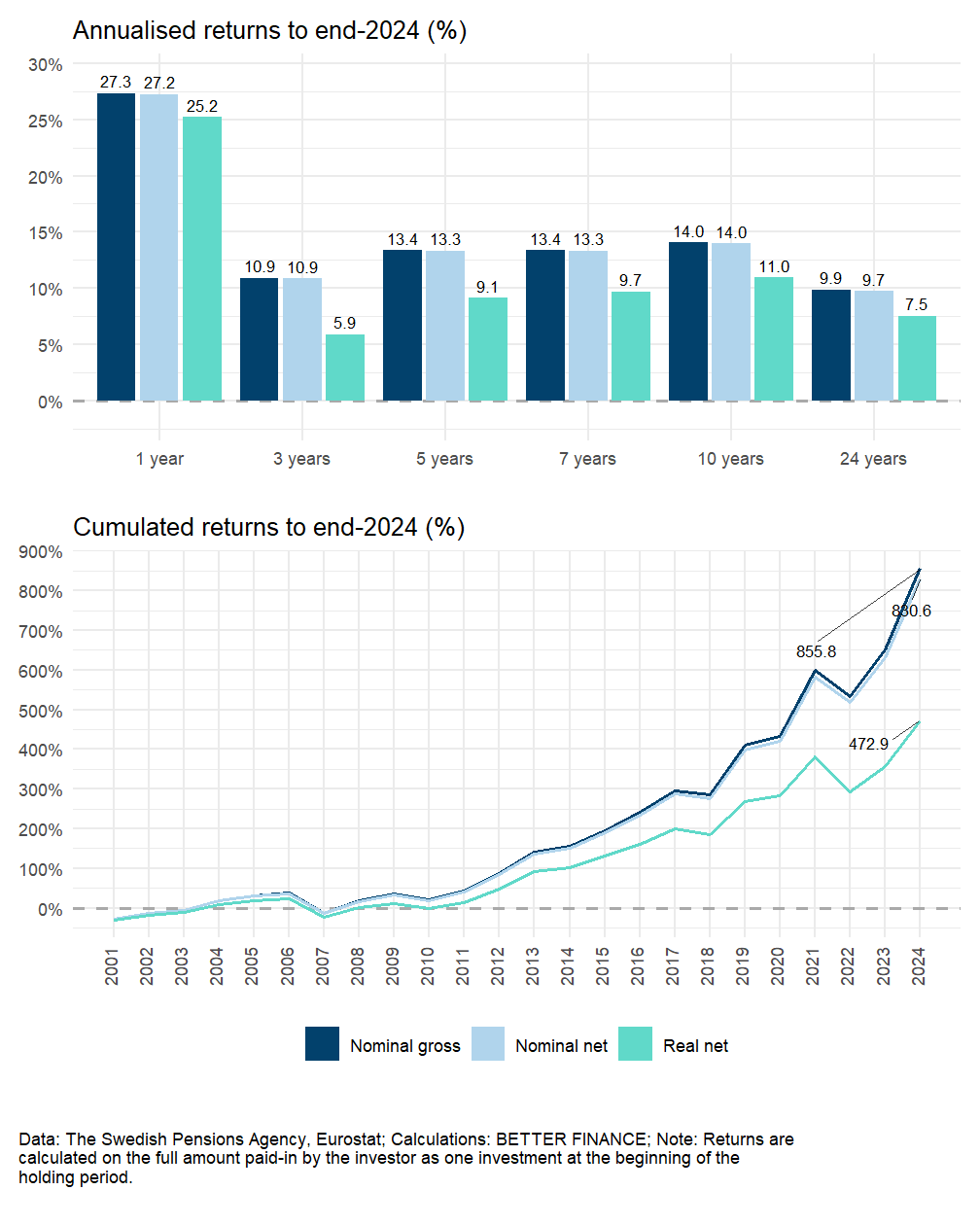

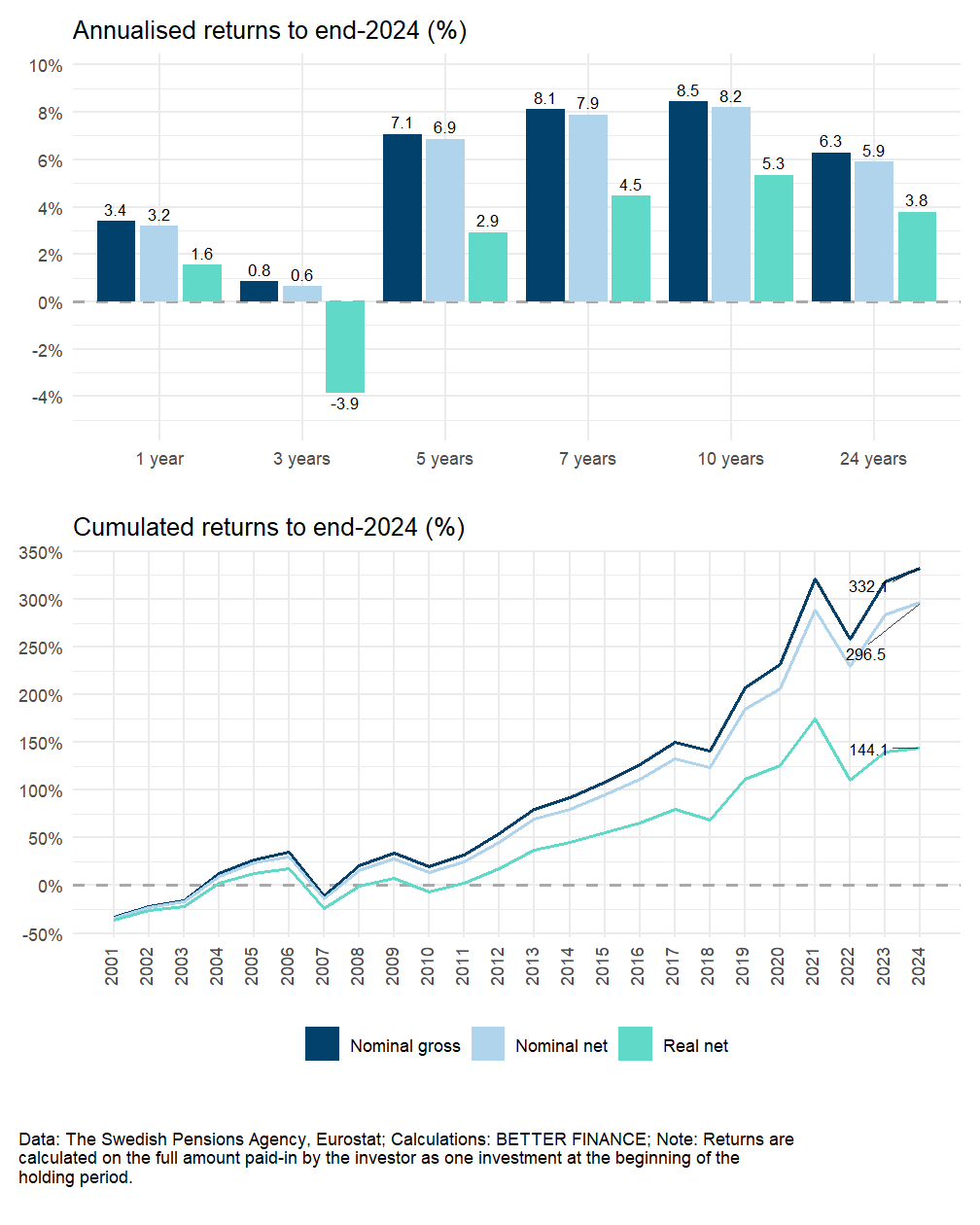

Figure 18.3 and Figure 18.4 show average annual returns for default investors and those who opted out of the default respectively. Each figure displays the nominal return, the nominal return net of charges, and the real return (net of charges and inflation) for year 2023 and in different horizons and compares the cumulated returns of the various products over their respective reporting periods. It is worth to note that the average fee for the default fund and for “active” investors in 2023 is 0.05% and 0.20%, respectively. The inflation rate (measured by harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP)) in 2023 was 1.86% (see Figure 18.2), slightly lower than the European average of 3.4%, which marked a notable decrease from 10.8% in the preceding year.23

Since the start of the premium pension in 2000, the default fund has on average performed better than the average “active” investor. The average annual real return for the default fund and “active” investors amounts to 6.8% and 3.9% respectively. It is important to remember that the “active” investors also include inert investors, i.e. investors that at some point made active contributions but then remained passive. The average returns for the “truly” active investors are therefore underestimated. In fact, Dahlquist, Martinez, and Söderlind (2017) find that investors who are actively involved in managing their pension accounts earn significantly higher returns than passive (inert) investors.

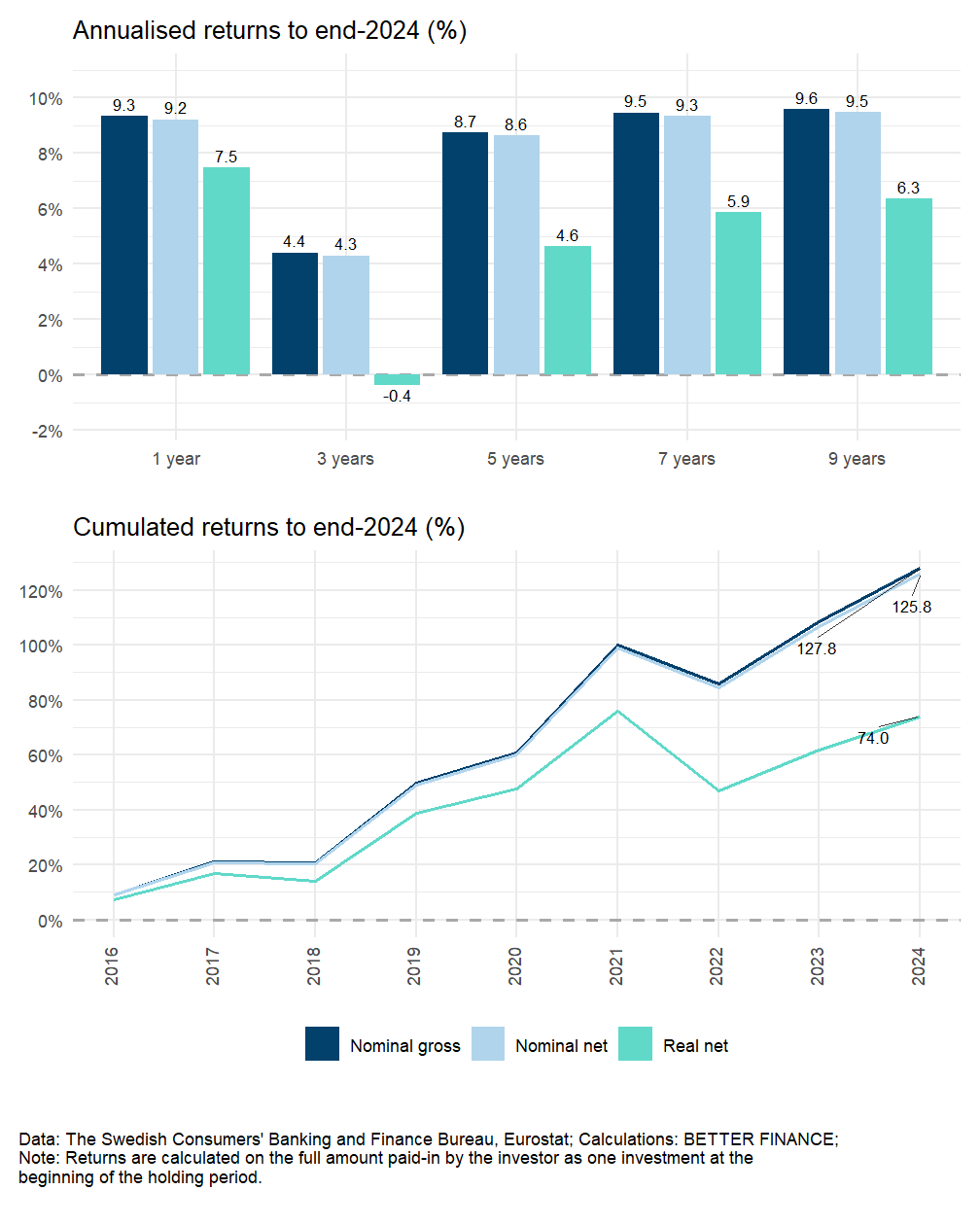

Figure 18.5, Figure 18.6, Figure 18.7, and Figure 18.8 illustrate returns within the occupational pension system. These figures present the average return, nominal return, nominal return net of charges, and real return (net of charges and inflation) for various occupational pension vehicles across different time horizons.

We can observe that, although the different categories of vehicles under the Swedish occupational pensions pillar have different pension products (in sizes and numbers), the returns are very similar from one year to another, as such the average on the last five years are almost the same.

Figure 18.9 summarises the annualized averages in the Swedish Premium Pension System and occupational pensions based on standardised holding periods (1 year, 3 years, 7 years, 10 years and since inception or the latest data available for this report). The figure (which reiterate data from the summary returns table at the beginning) is meant to provide better comparability with other pension vehicles in the countries analysed in this report. Figure 18.10, similarly, offers a comparative perspective of the cumulated performance of Swedish pension products.

Do Swedish savings products beat capital markets?

This section presents a comparative analysis of the real net returns for selected pension products in Sweden, specifically focusing on premium pension funds within Pillar I and ITP1 funds within Pillar II. The comparison is made against a “balanced” portfolio, comprised of 50% equity and 50% bonds, based on two Europe-wide indices, STOXX All Europe and Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index. The assessment is based on annualized returns across various holding periods and cumulative real net returns.

| Equity index | Bonds index | Start year | Allocation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premium pension - AP7 Såfa | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2001 | 50%–50% |

| Premium pension - Other funds | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2001 | 50%–50% |

| ITP1 | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2016 | 50%–50% |

| SAF -LO | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2016 | 50%–50% |

| PA - 16 Avd I | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2016 | 50%–50% |

| AKAP - KR | STOXX All Europe Total Market | Barclays Pan-European Aggregate Index | 2016 | 50%–50% |

| Data: STOXX, Bloomberg; Note: Benchmark porfolios are rebalanced annually. | ||||

Figure 18.11, Figure 18.12 and Figure 18.13 illustrate the performance of premium pension and occupational funds relative to the benchmark portfolio. Overall, the figures show that the real returns for the pension products in Sweden track the development of the capital markets and have been following a predominantly favourable trend over time. In addition, the results reveal a consistent overperformance of the savings products compared to their respective benchmarks since 2001 and across different investment horizons. For instance, over the 2001–2021 period, the annualized returns of AP7 Såfa and other funds (in Figure 18.11) were 3.1 and 1.7 times higher, respectively, than the benchmark fund. Over a similar period, the cumulative returns (second panel in Figure 18.11) for the default and other funds within the premium pensions exceeded the benchmark by 237% and 50%, respectively.

This trend extends to various asset classes, including occupational pensions, as shown in Figure 18.12 and Figure 18.13. It’s worth noting that the performance of other Pillar II funds closely mirrors that of ITP1 funds. During the same period, ITP funds delivered an annualized return of 10% , surpassing the benchmark fund, which recorded a return of 0.9%. For ITP1 (dark blue in Figure 18.12), the cumulative return during this period was 61.39%, while the benchmark returned 0.97%.

The strengthening of the financial position of the pension products can be attributed to the fact that the products contain a well-balanced portfolio across different products and exposure to the global and Swedish markets, making them positioned to benefit from the prevailing market situation.

18.6 Conclusions

The Swedish pension system is considered robust and sustainable. The balancing of the income-based system contributes to preserving the system’s debt balance and secures the long-term nature of the system. The premium pension, which is a system unique to Sweden, also contributes towards spreading the risk in the system and enhancing the return on capital by enabling people to place part of their national pension capital on the stock market. As a result of the change in the Swedish pension system, individual responsibility will increase, and the occupational pension will constitute a bigger part of the total pension in the future.

The occupational pension system in Sweden covers more than 90 percent of the working population. The collectively negotiated pension schemes are procured for a large number of workers, which leads to lower costs, and more transparent pension plans. Individual occupational pension plans and third-pillar pension accounts are, however, often characterized by higher management fees, deposit fees and less transparency.

The statistics on net returns in the second and third pillar pension plans are quite cumbersome to collect. The Swedish Consumers’ Insurance Bureau reports fees and returns in most pension plans, but there is no immediately available information on net returns. It is also difficult to calculate historical returns in the second pillar because the set of funds that the retirement savers can choose from might change, for example due to procurement.

A source of concern is that the pension system is becoming increasingly complex. The number of occupational pension plans per individual is increasing both because job switches across sectors become more common and because pension capital can be moved between companies. The ongoing transitions between old and new occupational pension plans also contribute to the increased complexity of the second pillar. All three pillars also contain many elements of individual choice both during accumulation and decumulation phase.

Pension systems that are too complex risk leading to inertia and distrust, which in turn could lead to worse saving and retirement outcomes. Well-designed default fund options with low fees and appropriate risk exposure as well as comprehensive, user-friendly information/choice centers are necessary features in a complex pension system.

Although the Swedish pension system is considered robust and sustainable there is reason to be concerned. As life expectancy increases, the gap between wages and pensions will increase. The average exit age from the labour force has been increasing ever since the new public pension system was implemented in the late 1990s and is currently 64. However, the average claiming age has been constant.24 The combination of constant claiming age, later labour force entry among youths, and indexation of pension benefits to life expectancy unavoidably means lower pension benefits.

The concern of decreasing replacement rates in the public pension system has spurred an intense political debate about raising the public pension. In June 2022, the parliament passed a historically large increase of the minimum guarantee equal to SEK 1000 that will be implemented just prior to the national election of 2022. In addition to raising the minimum guarantee (and the means-tested housing allowance), the pension bill of 2022 also stipulates that a “pension gas” should be introduced in the income pension. The pension gas is the equivalent of the automatic balancing mechanism in the sense that it distributes excess capital to pension savers and retirees when system assets exceed system liabilities by a certain amount.

As calls for pension reforms have intensified, there are also recent reports that give a more nuanced picture of pensioners’ finances. A report by the Swedish Fiscal Policy Council25 which was published on 6 May 2022 found that relative to the income development of the working population, the income of pensioners has also risen throughout the distribution since the reformation of the public pension system in the early 90s. Compared to the 34–64 age group, pensioners’ disposable income has developed favourably at both the bottom and top of the income distribution — while the development of those in the median income part of the distribution has been similar to the compared age group. According to the report, new pensioners have been able to sustain relatively high replacement rates mainly due to increased labour income and occupational pensions. Occupational pensions constitute 29% of outgoing pension payments and play a relatively more important role for high-income earners.

Since the retirement age has not increased in relation to life expectancy, the accrued pension entitlements have had to suffice for more and more years in retirement. One way to raise pension levels is to increase the pension contribution. But it should be remembered that fee increases reduce the salary space for those who work and are also not a viable path in the long run. The most important thing for pensions is a high level of employment and that working life is extended when we live longer. In particular, the Swedish Fiscal Policy Council points to the low employment rate of low-skilled and foreign-born people as a problem in the future. Also, certain groups on the labour market that are already at risk of receiving a low pension (such as gig workers, self-employed and immigrants) are often not eligible for an occupational pension.

To encourage later retirement, policy makers have agreed to raise various retirement ages in a stepwise manner. By 2026, the minimum claiming age, the eligibility age for the minimum guarantee, and the mandatory retirement are expected to have increased to 64, 67 and 69, respectively (currently at 63, 65 and 68, respectively). The 65-norm is still strong in the second pillar, however. In the private sector, pensions are usually paid out automatically at this age, and pension rights are in most cases not earned after this age. As replacement rates fall, individuals also need to take more responsibility for their private pension savings. This makes accessible good pension savings products with low fees even more important.

Policy recommendations

- Expand the portability right of second pillar pension capital.

- Improve information on historical net returns and other fund characteristics in second and third pillar pension plans.

- The digital pension tool www.minpension.se makes it possible for individual retirement savers to collect information on their total pension savings. Since 2019, there is a related tool for planning pension withdrawals. A useful extension would be to allow users to execute their pension fund choices from this site.

- Replace automatic payment of occupational pensions at a certain age with a claiming requirement (as in the public pension system).

Acronyms

- AuM

- assets under management

- EEA

- European Economic Area

- EET

- Exempt Exempt Taxed

- ETT

- Exempt Taxed Taxed

- EU

- European Union

- HICP

- harmonised index of consumer prices

- IPS

- individual pension savings account

- ISK

- Investeringssparkontot

- PAYG

- pay-as-you-go

Outflow payments totalled SEK 603 billion (EUR 54.3 billion) in 2022.↩︎

Based on information retrieved from: https://www.pensionsmyndigheten.se/statistik/pensionsstatistik/. Note that the average pension must be weighted with the number of people receiving a pension from a particular pillar.↩︎

See Hagen (2017) for a more detailed description of the Swedish Pension System.↩︎

EUR 54 037 EUR (SEK 599 601) for 2023.↩︎

Vägval för premiepensionen, Ds 2013:35.↩︎

The Swedish Pensions Agency, Orange report p34.↩︎

The Swedish Pensions Agency, Stärkt konsumentskydd inom premiepensionen.↩︎

https://www.pensionsmyndigheten.se/nyheter-och-press/pressrum/nytt-avtal-klart-for-premiepensionens-fondtorg↩︎

Socialdepartementet, Ett bättre premiepensionssystem, Prop. 2021/22:179.https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/proposition/ett-battre-premiepensionssystem_h903 179/↩︎

https://www.fondbolagen.se/aktuellt/pressrum/pressmeddelanden/forslagen-i-utredningen-ett-battre-premiepensionssystem-gar-emot-malen-med-premiepensionen/↩︎

AMF, “Tjänstpensionerna i framtiden — betydelse, omfattning och trender”, p. 17; ISF Rapport 2018:15, “Vem får avsättningar till tjänstepension”.↩︎

https://www.pensionsmyndigheten.se/forsta-din-pension/tjanstepension/det-har-ar-tjanstepension↩︎

Konkurrensverket, Flyttavgifter på livförsäkringsmarknaden — potentiella inlåsningseffekter bland pensionsförsäkringar, Rapport 2016:12.↩︎

Ministry of Finance, “En effektivare flytträtt av försäkringssparande”.↩︎

Ministry of Finance, “Avgifter vid återköp och flytt av fond- och depåförsäkringar”.↩︎

Finansutskottets betänkande, “En ny reglering för tjänstepensionsföretag”. See https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/betankande/en-ny-reglering-for-tjanstepensionsforetag_H701FiU12/ for more information on IORP II.↩︎

The Swedish Pensions Agency, Orange report 2022, page 33.↩︎

The Swedish Pensions Agency, Orange report 2023, page 33.↩︎

SOU 2012:64, page 466↩︎

Deductible contributions amount to maximum 35% of the wage of the employee. However, the deduction cannot exceed 10 price base amounts.↩︎

The Swedish earned income tax credit is a refundable tax credit for all individuals aged below 65.↩︎

Financial year 2021: https://www.skatteverket.se/privat/skatter/beloppochprocent/2022.4.339cd9fe17d1714c0 774 742.html↩︎

This is mainly due to reduced disability pension rates (through stricter eligibility rules), which affects the exit age but not necessarily the claiming age if people claim their pension instead. Another explanation is that individuals who work past the age of 65 do not postpone the withdrawal of their pension.↩︎

The main results and conclusions are reported by the Swedish Fiscal Policy Council (2022) while Hagen, Laun, and Palme (2022) contain the complete set of empirical analyses.↩︎